According to French media reports, Sylvain Amic, chairman of the Musee d'Orsay and the Musee de l'Orangerie in Paris, died of a sudden heart attack in southern France on August 31 local time at the age of 58.

Since taking office in April 2024, Sylvain Amick has launched numerous projects aimed at bringing audiences who feel alienated, excluded, indifferent, or discouraged closer to this world-renowned institution. In mid-June of this year, he visited Shanghai and presented the exhibition "Creating Modernity: Art Treasures from the Musee d'Orsay in Paris."

In mid-June this year, when the Shanghai Pudong Art Museum opened its exhibition "Creating Modernity: Art Treasures from the Musee d'Orsay in Paris", he came to Shanghai and, in an interview with "The Paper Art Review", talked about his thoughts on the future of the Musee d'Orsay.

Although Amick has visited China many times in the past three decades, this year is his second time in Shanghai. The first time was in 2019, when he was the director of the Rouen Museum in Normandy, France, and curated an exhibition on abstract art, which was exhibited at the Shanghai Minsheng Art Museum. During his visit to Shanghai, he also went to the West Bund Art Museum to learn about the exhibition of his colleagues at the Pompidou Center in Shanghai. In his opinion, "There are many cultural projects initiated by French cultural institutions in Shanghai, which never only show one aspect of French culture, but an open artistic vision. This also shows the city of Shanghai's high understanding and appreciation of art, as well as the important position of art in contemporary society."

Amick (second from left) at the exhibition

Sylvain Amick was born in Senegal on April 26, 1967, and is a French art historian. A member of the Rouen Academy of Sciences, Letters and Arts, he served as director of the Musée d'Orsay from 2024 to 2025. Regarding the Musée d'Orsay, he emphasized in an interview with Le Monde in January of this year: "The Musée d'Orsay is a museum of the Republic, a national treasure that must be returned to the entire nation," and "an open museum means it must act together with civil society." In an interview with The Paper, he also mentioned that "as a 'national museum,' the Musée d'Orsay must first be open to all French people, not just the elite or Parisians. France is diverse, with people from different countries and cultural backgrounds, each with their own experiences and concerns. How can we make all these people from different backgrounds feel at home in the museum—feeling welcomed, treated equally, and taken seriously?"

He also discussed the 40th anniversary celebrations being planned for the Musée d'Orsay. However, this mission statement came to an abrupt end. Amick's death has left the teams at the Musée d'Orsay and the Musée de l'Orangerie devastated and his colleagues in the field in shock.

His predecessor, Christophe Leribeau, described the news as "a shock" on social media. Leribeau, who now directs the Palace of Versailles, praised Amick as "a dedicated, energetic, and warm person." French Culture Minister Rashida Dati, who appointed him as director, also paid tribute to him, calling him "an open and creative mind." Former Culture Minister Rima Abdel-Malak, a close friend of Amick, recalled him as "a man totally dedicated to public service."

Appendix: An interview with Sylvain Amick by The Paper on June 17, 2025

Exhibition Talk: Bringing together masterpieces, presenting the many moments in the birth of modern painting

The Paper: How do you summarize and interpret the 107 paintings and sculptures exhibited in “Creating Modernity”?

Amick: An exhibition is a time-limited experience, taking years to prepare but lasting only a few months. This is a very special moment. France played a central role in the global landscape in the 19th century. That's why we approached this exhibition with such a comprehensive approach, bringing together masterpieces and showcasing key moments in the birth of modern painting.

This exhibition begins by revisiting the architectural context of the Musée d'Orsay itself. The Musée d'Orsay was originally a railway station—a significant development in itself. Initially, it wasn't built to exhibit art, but rather as an industrial space.

At the exhibition site, the iconic clock of the Musee d'Orsay allowed the audience to enter the context of the exhibition and also became one of the "check-in points".

This kind of architecture offers a unique perspective on that era. Constructed of iron and steel—in fact, the Orsay Station has more steel than the Eiffel Tower—it symbolizes the industrialization of late 19th-century France and the rhythm and power of an era.

The exhibition unfolds within this imaginary industrial architecture: we begin in an old world ruled by fixed ideas, religious doctrines, and art academy norms, and see how these rules are gradually questioned and deconstructed, ushering in the birth of new art.

The exhibition entrance features two works with Old World motifs: Jean-Léon Gérôme's "Young Greeks Playing Cockfighting," 1846 (left) and Alexandre Cabanel's "The Birth of Venus," 1863 (right).

The exhibition opens with works entirely influenced by the French Academy tradition, featuring idealized nudes, figures from classical mythology, and compositions that bear little resemblance to real life. However, soon, with the arrival of Courbet and Millet, and later the Impressionists, we see "reality" itself enter painting: natural landscapes, workers, peasants, street children, the contrast between the city and the countryside—all these social realities begin to dominate artists' canvases.

Millet's "The Gleaners" exhibition hall, surrounded by works by artists such as Courbet and Bastien-Lepage

This is not just a shift in subject matter, but also a reshaping of the essence of art: no longer expressing an idealized world, but facing the changes and turmoil that are taking place.

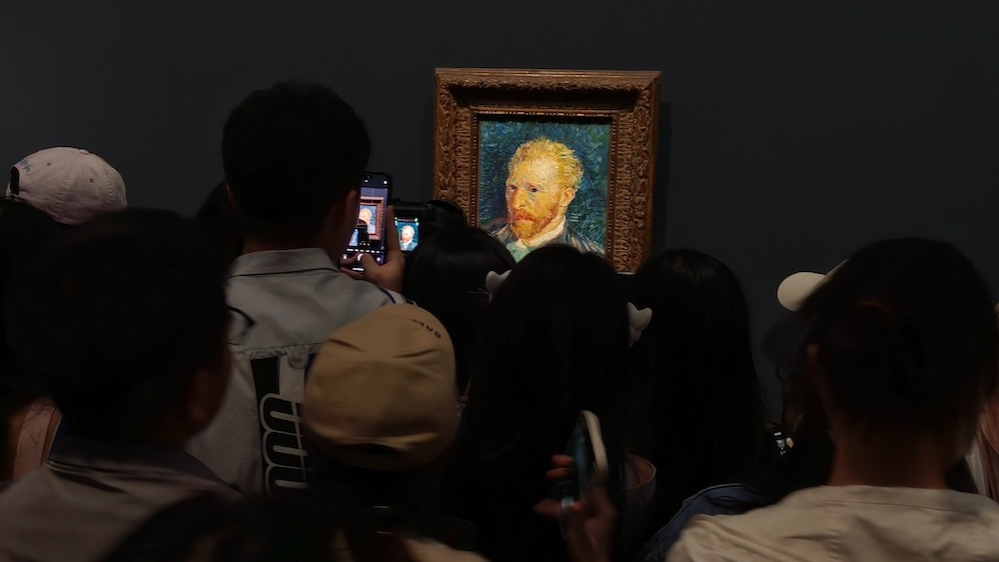

At the same time, we can also see how artists constantly reflect on themselves in their self-portraits. No longer simply the worshipped "creators" in their paintings, they are now contemplating their own place and significance as modern individuals within this new social structure. This is a search for identity and a spiritual confession.

All of this unfolds quietly in the exhibition, constituting a profound transition from tradition to modernity.

The last exhibition hall of the exhibition displays works by the Nabis.

The Paper: The interweaving of the works presented in the exhibition reminds us of Gombrich's concept of "image ecology," which emphasizes that images must be recontextualized within their social and historical contexts to truly gain meaning. What role do images play as messengers in cross-cultural dialogue?

Amick: Images have an extraordinary power. They can touch us directly without the need for words.

Because of this, the power of images is twofold: on the one hand, they can transcend the boundaries of language and culture and immediately generate emotional resonance; on the other hand, this power can also lead to misunderstandings. If it lacks the support of background knowledge and historical context, it may be misinterpreted, misunderstood, or even abused.

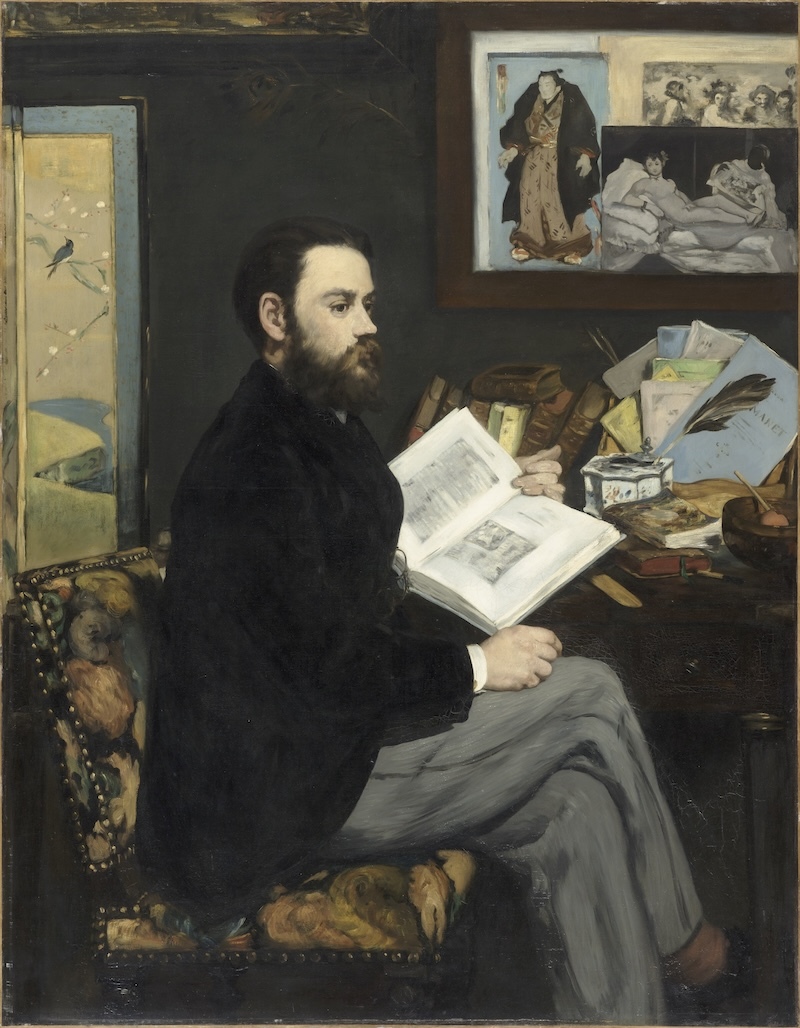

Édouard Manet, Émile Zola, 1868, oil on canvas © photo: Grand Palais Rmn (Musée d'Orsay) / Patrice Schmidt

This is precisely the role of museums: they are not just spaces for displaying images, but also places that give these images context and deeper meaning. Through their academic training and curatorial logic, museum researchers and curators provide audiences with a path to "see," allowing them to understand why these images were created in the way they were, when they were produced, and what social contexts they responded to.

Charles-François Daubigny, Spring, 1857, oil on canvas © photo: RMN-Grand Palais (Musée d'Orsay) / Hervé Lewandowski

At the same time, images retain a primal, cross-cultural immediacy. Just as humans expressed and communicated through images before the invention of writing, the power of images is ancient and universal, and therefore must be channeled and interpreted.

When we bring these works to another cultural context, such as this one in Shanghai, we're very aware that audiences will react differently because they have their own cultural experiences and visual habits. Understanding these differences is a process of mutual engagement and listening. We try to understand how Chinese audiences view these images within their own cultural context, while they, in turn, try to understand the meaning of these works within a French or European context.

Exhibition view, Paul Cézanne, "Portrait of Madame Cézanne," 1885-1890, oil on canvas

Every exhibition like this is a two-way process: we take a step toward each other, and they also move closer to us. This mutual understanding and learning between cultures is the most fascinating and precious aspect.

On Cooperation with China: Re-examining France through the Eyes of Others

The Paper: This exhibition is the largest exhibition of the Musee d'Orsay in China to date. Could you talk about your impression of Shanghai and your collaboration with the Pudong Art Museum?

Amick: I first came to Shanghai five years ago when I was director of the Rouen Museum in Normandy, France, and curated an exhibition of abstract art at the Shanghai Minsheng Art Museum. But I've been to China many times over the past three decades. For me, Shanghai is a very special city, brimming with modernity and possessing the power to control its future and destiny.

In 2019, Amick, then director of the Rouen Museum, curated the exhibition "Invisible Beauty" at the Shanghai Minsheng Art Museum. The picture shows him guiding the audience at the exhibition site.

I was in a hurry in Shanghai this time and didn't have much time to visit, but I went to see the West Bund Art Museum to see what my colleagues at the Pompidou Center are doing there. The ongoing exhibition explores the theme of "landscape" and features not only French artists but also creators from all over the world.

West Bund Art Museum and Centre Pompidou’s five-year collaboration project, permanent exhibition “Reshaping the Landscape: Collections from the Centre Pompidou (IV)” at West Bund Art Museum. Photo by Alessandro Wang

I'm delighted to see that many cultural projects initiated by French cultural institutions in Shanghai showcase not just one aspect of French culture, but an open artistic perspective. This also demonstrates Shanghai's deep understanding and appreciation of art, and the important role of art in contemporary society.

We've noticed that the Shanghai public is very interested in cultural projects and art, especially French art, and is eager to see a variety of open and diverse artistic presentations. This venue has previously hosted numerous exhibitions covering different eras and cultures. I'm honored that France is participating and presenting an exhibition of this caliber and quality.

At the Pudong Art Museum, we felt the extremely high professional standards and witnessed the organizers' outstanding ability to organize major exhibition projects.

Curating an exhibition requires tremendous investment and effort, so finding the right partners is crucial to achieving the best possible outcome. We've already begun exploring future collaborative projects. While these will take several years to develop and prepare, we can be sure that we will continue our collaboration with the Pudong Art Museum, and we may also explore new exhibition projects elsewhere in China. We'll see.

Audience in front of "The Gleaners" at the Pudong Art Museum

Another important work of Millet, "The Vespers" in the Orsay Museum

The Paper: How do you understand a national museum’s responsibility for self-expression when facing a “global audience”?

Amick: This is something I think about every day, and it's the fundamental difference between a national museum and any other museum: as a national museum, we must first and foremost be open to all French people, not just the elite or Parisians. This is why we need to develop strategies to make the Musée d'Orsay's exhibitions accessible throughout France, even to places without museums. For example, we're developing a "museum truck" to bring art to regions that haven't had museums before.

France is diverse, with people from different countries and cultural backgrounds, each with their own experiences and concerns. How can we make all these people feel at home in the museum—that they feel welcome, treated equally, and taken seriously? This means that before we can tell our story to the world, we must first learn how to engage with France's diversity.

The Musee d'Orsay on June 18, 2025

At the same time, the museum has another important mission: to reach out to the world. Next year will mark the 40th anniversary of the Musée d'Orsay. Historically, our international collaborations have primarily focused on Western countries, with some exposure to Asia. However, collaboration with China has been very limited, and there has been virtually no engagement with Africa, the Arab world, or South America.

Therefore, the challenge before us is: how to truly become a "global" museum - an institution that operates around the world and engages in dialogue with the world.

Manet's "Boy with the Piccolo" was exhibited in Shanghai in 2004.

This visit to China is of extraordinary significance. China is a great country with a long history, a land steeped in cultural traditions, and one with deep cultural ties to France. Furthermore, China boasts a vast population. For us, China is not only a key cultural partner but also a vital window into Asia and the rest of the world.

This also means accelerating our research to delve deeper into the exchanges and interactions between France, Asia, and China during the period covered by the Orsay exhibition. Artists traveled to China, and Chinese collectors, diplomats, and travelers visited France. These cultural connections existed historically, and we need to do more research to understand them. Therefore, our visit to China is not only about connecting with Chinese audiences, but also about deepening our understanding of our own history—and, from there, reaching out to other regions we haven't yet truly reached.

We need these external perspectives to look at French culture and art and discover new meanings in them.

Visitors take photos at the entrance of the exhibition "Christian Klauhe: People of the North" at the Musee d'Orsay in Paris, France, on March 20, 2025. The exhibition is the first retrospective of the Norwegian painter Christian Klauhe outside of Scandinavia and concludes the Musee d'Orsay's trilogy on Norwegian art from the early 20th century. The exhibition will run until July 27, 2025.

Talking about "Impressionism": Re-understanding Impressionism 150 Years After Its Birth

The Paper: Last year, the Orsay organized a series of commemorative projects for the 150th anniversary of Impressionism. As the leading institution of this "grand narrative," was the Orsay attempting to rediscover Impressionism and reposition it in a global context?

Amick: Taking advantage of the 150th anniversary of the birth of Impressionism, we raised the question of "How to re-understand Impressionism?"

This is also an opportunity to share these works with as many audiences as possible. Over the past year, we have loaned many masterpieces to various locations in France, and in Paris, we have curated an exhibition that looks back to the first Impressionist exhibition in 1874 – attempting to show that the birth of this movement did not happen in isolation. For too long, in the interest of simplifying the narrative, people have intentionally or unintentionally ignored the complex context of the time.

Exhibition view of "Paris 1874: The Making of Impressionism" at the Musee d'Orsay

Impressionism was undoubtedly a revolution, but it was more than just a break; it also possessed profound continuity with previous traditions. In other words, it stood at the intersection of "break" and "continuity." It is precisely this complexity of history that we hope to showcase. This is precisely one of the significances of this Shanghai exhibition: it reveals that the struggles among artists were far from a clear-cut struggle between camps, but rather a process of intellectual collision and collaboration within diverse schools, collectively giving birth to a "new painting."

Therefore, this is also a way for us to re-examine the formation of Impressionism. Impressionism, like all major art movements, deserves further investigation. One particularly interesting perspective is its relationship to the world.

Édouard Manet, Woman with a Fan, 1873-1874, oil on canvas © photo: Musée d'Orsay, Dist. RMN-Grand Palais / Patrice Schmidt

For example, its influences from Asian art are well-known. But let's not forget that it was collectors who helped spread Impressionism around the world. Each time it was transplanted, new pictorial languages emerged in different parts of the world. We can see its influence in Asia, the United States, and even the Arab world. Therefore, Impressionism has become a truly global phenomenon. It's also why these paintings are so popular, and why audiences around the world are eager to see them in person. But I believe that research into these issues is only just beginning.

In 2024, the National Museum of Western Art in Tokyo, Japan, included an exhibition hall in the exhibition "Monet's Water Lilies Period" that displayed Monet's water lilies collected in Japan.

The Paper: While commemorating Impressionism, how does the Musée d’Orsay sort out the influence of its collection on the writing of 20th-century and even contemporary art history?

Amick: This also represents how we think about the future of museums and how we connect with the public in the present.

Over the years, we have continuously strengthened one direction: inviting contemporary artists to engage in dialogue with the collection. Because these works have become "image icons" familiar to audiences around the world, artists willing to engage in dialogue with them come from all over the world.

For example, we recently showed a Brazilian artist, Lucas Arruda, who was our first artist from the Southern Hemisphere. He was very interested in the Musée d'Orsay's collection, a sentiment shared by many artists – that the Musée d'Orsay's collection is not only important but also remains relevant today.

Installation view of Lucas Arruda's "What's Wrong with the Scenery" at the Musée d'Orsay

We also organized a special project called “Le Jour des Peintres” (A Painter’s Day), which took place on September 19th of last year. On this day, we invited 80 contemporary artists, aged between 30 and 77, to bring one of their works and place it next to their favorite Orsay pieces.

Contemporary artists and their works are presented side by side with 19th-century art, making us realize that this is not just a generational issue, but a strong emotional resonance, and they are also proud to be adjacent to the works of their role models.

"Painter's Day" event poster

More importantly, this is a way for contemporary artists to re-examine past art in their own way, not through academic interpretation, but with a fresh perspective. This is also the direction that the Musée d'Orsay is paving the way for the future: giving history new vitality through the participation of artists.

The Paper: In your opinion, what is the key to Impressionism still inspiring such international resonance 150 years after its birth?

Amick: I believe that Impressionism is still worth our continued revisit and exploration, because it is an extremely rich artistic phenomenon and we can always discover new meanings from it.

Camille Pissarro, Red Roofs of a Village in Winter, 1877, oil on canvas © photo: Musée d'Orsay, Dist. RMN-Grand Palais / Patrice Schmidt

For example, we're now re-examining Impressionism through the lens of climate and biodiversity. We're realizing that the Impressionists were also among the first artists to advocate for nature conservation. They also helped establish France's first national forest park, such as the Forest of Fontainebleau. The concept of "natural park," as we take it for granted today, actually originated in their 19th century era—when people began to recognize that nature was disappearing and that the traditional natural world was under threat.

This is a new interpretation of Impressionism: they were not only pioneers of the artistic revolution, but also forerunners of environmental awareness and "early warnings" sensitive to climate and the survival of nature.

Exhibition view, Constantin Meunier's "Black Land" circa 1893

Of course, there are many other themes worth exploring. For example, the role of female artists, which we have already explored in our exhibitions, and the topic of modernity. In this exhibition at the Pudong Art Museum, we also explored the role and significance of Impressionism through the lens of industrialization and urban transformation.

I have always believed that the most powerful cultural phenomena are constantly reinterpreted and rewritten by generations, constantly responding to contemporary issues. This is precisely the charm of Impressionism—it is far from exhaustive, and it always offers new surprises and inspirations.

"Creating Modernity: Art Treasures from the Musee d'Orsay in Paris" exhibition

On the Orsay Museum: Responding to Current Issues in a 19th-Century Museum

The Paper: Compared with other French museums such as the Louvre, which collects ancient art, and the Pompidou Museum, which collects modern and contemporary art, what else makes the Orsay unique besides its collections and research?

Amick: The Louvre occupies the past, the Pompidou Centre looks to the future, and the Musée d'Orsay focuses on a very narrow period—just 75 years: from 1848 (the February Revolution) to 1914 (the outbreak of World War I). This period may sound short, but its density and significance were immense: science, art, politics, economics—almost everything underwent radical transformation. The contemporary world we live in was born during this period.

Therefore, the challenge we face is how to open a "narrow" window of time and show the public its decisive significance in understanding contemporary society and even facing current problems.

"Art in the Streets" special exhibition at the Musee d'Orsay in Paris

This period, with its glories and shadows, laid the foundation for the present and the future. Climate change was first recognized in the 19th century, and colonialism is also a significant legacy of this century. But it was also the era of the invention of vaccines, the birth of film, the laying of railways, and the beginnings of technology and modern lifestyles.

This was a highly charged and complex period, a crisscross of hope and contradictions. It is not just history; it continues to shape us. Therefore, an in-depth study of this period is crucial to our understanding of the world today.

The Paper: As the "temple of 19th-century art", how can museums transform from "guardians of classics" to "storytellers of the future"?

Amick : Indeed, the primary mission of a museum is to preserve – but preservation is meaningless if it is not used by people.

Even though people in the past made great efforts to preserve art, we still need to ask ourselves: Is this concept still relevant today? Therefore, the way we work is to make the museum as "contemporary" as possible - by responding to today's problems and showing how the collection, art history and the history of that era are still important resources for us to understand the world and draw inspiration from it.

For example, the status of women in art and society was a highly charged issue in the 19th century, and to this day, it remains a focal point of public discussion in Western societies and even in Asia.

"Creating Modernity: Art Treasures from the Musee d'Orsay in Paris" exhibition

We can revisit this question by drawing on the collection itself and the history of the artists and models. In this way, a contemporary issue can be addressed in a museum whose core is the 19th century. This is a vivid example of how we can make the museum "up-to-date."

The Paper: In recent years, the Musée d'Orsay has also been active in the digital realm, with initiatives like virtual exhibitions, social media campaigns, and immersive collaborative projects. Do you think digitalization will change the museum's power structure?

Amick: Digital technology is an extremely valuable tool, and we are constantly expanding our practices. For example, in this exhibition, visitors can use virtual reality to personally "travel" to the first Impressionist exhibition in 1874 - an experience that cannot be achieved in a real-life exhibition.

Scenes from "Paris 1874: Impressionist Night – An Immersive Exploration Experience"

It is a channel to the past and a way to help us better understand the context of the exhibition. We mentioned earlier that to understand the works, we must understand the context of the times in which they were created, and virtual reality provides such an opportunity.

For us, this technology offers a new possibility: to make art accessible to a wider audience without having to use the original work every time. Artworks can't be in multiple locations simultaneously, but technology can. For example, this immersive experience is currently being simultaneously displayed in Dubai, France, and the United States. Relying on the same technology platform, audiences in different locations can share the same experience.

Of course, a real work of art is a kind of "one-time" encounter, and the advantage of virtual technology is that you can repeat it many times, become more familiar, and be more proactive in exploring the details of art history.

I'm not at all worried that this technology will diminish the audience's experience with the artwork itself—historically, photography, film, television, and the internet never replaced museums. Neither will new technologies. On the contrary, they are extremely powerful auxiliary tools, helping us understand art more deeply and comprehensively.

- TLbujaUaW09/03/2025

- JMRTQlLLhZmuaJz09/02/2025

- ahfkGAIgdUgcu09/02/2025

- QZSuxCVp09/02/2025