The Berlinische Galerie Museum für Moderne Kunst (Berlinische Galerie Museum für Moderne Kunst), located in Berlin, Germany, is an art museum affiliated with the Berlin State Museums. It specializes in collecting Berlin's urban art, with a notable distinction: it exclusively collects German modern art from the mid-to-late 19th century to the end of the 20th century. Recently, I visited the Berlinische Galerie Museum für Moderne Kunst's latest exhibition, "Performances of the Self: Photography by Martha Fitz," and conducted an exclusive interview with its director, Thomas Köhler.

The exhibition of film photographs dating back 100 years offers a sense of discovery, akin to discovering a treasure trove. The tiny films, their black-and-white images tinged with the yellow of time, transport visitors to a wondrous world they've never experienced before: Berlin during the Weimar Republic.

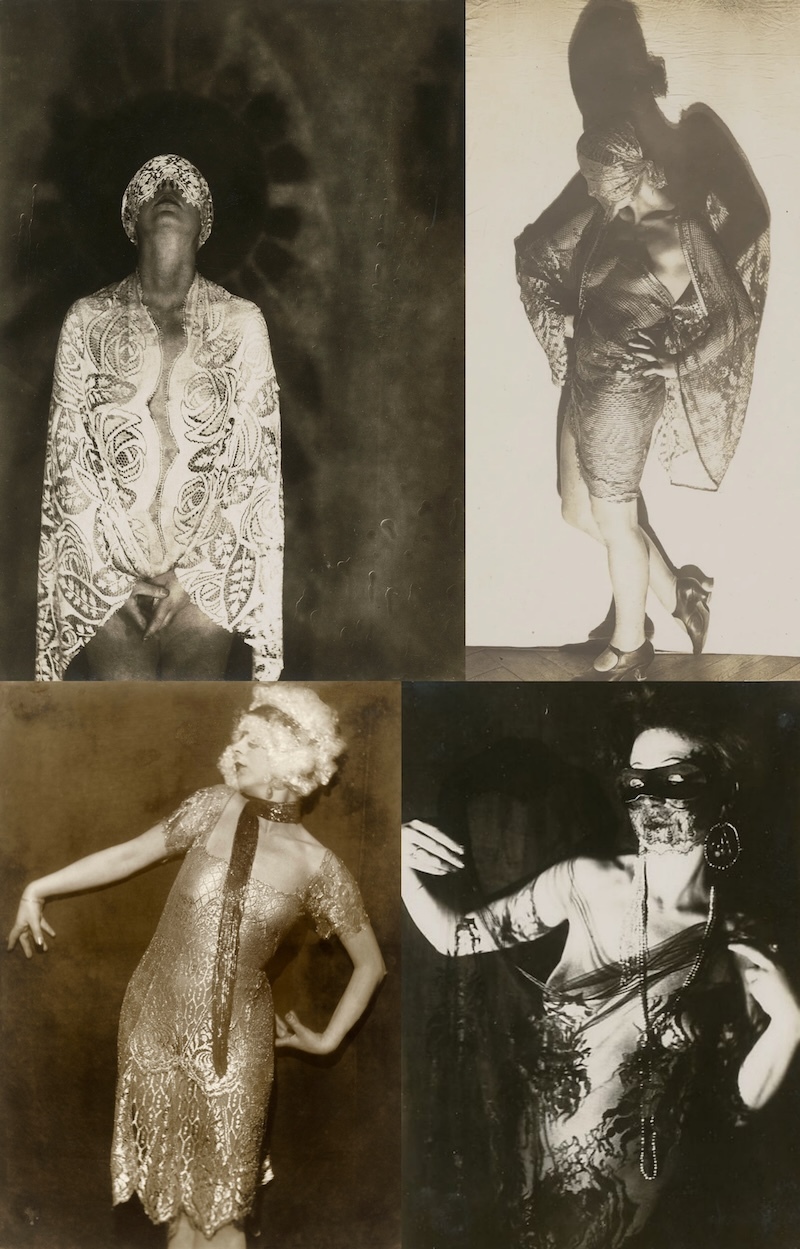

Fitz, Untitled, 1927. Courtesy of Berlinische Galerie

This year marks the 50th anniversary of the Berlin Gallery. "Fetz Photographs," a commemorative exhibition, aims to enrich the landscape of modern German photography by rediscovering this often-overlooked artist. Though created 100 years ago, Fetz's images remain timeless. Today's popular selfies, cosplay, fashion editorials, costumes, and staged photography were mastered by German photographers a century ago. His exquisite composition and adventurous ingenuity remain unmatched even with today's advanced digital technology and shutter speeds.

Sadly, this talented artist's photographic career ended at the age of 32. For the next 60 years, this exceptional photographer lived in obscurity as an "art teacher" and a charitable act reminiscent of a "good German." The Nazis and the war weren't mere chapters in history books; they were a mountain weighing heavily on Fitz's shoulders. Fitz's unrelenting talent epitomized the tragic legacy of German art: its invisibility wasn't due to its lack of beauty, but rather the shroud of historical and national tragedy, or perhaps its destruction simply due to its sheer beauty. Yet, the mystery of history lies in its impermanence: because of impermanence, Fitz's photography was buried; and thanks to this impermanence, Fitz's work has miraculously rediscovered, a symbol of hope for German art.

Weimar Germany in Images: Private Introspection and Social Insight

On a rainy July day, I visited the Berlin Gallery in Kreuzberg, Berlin. Thirty-five years ago, this area was still "West Berlin," surrounded by the Berlin Wall. Today, it's Berlin's most vibrant cultural and artistic district. The Berlin Gallery was founded here in 1975.

Exhibition view Berlinische Galerie

Why only collect modern art? "Our space is too small to accommodate so much contemporary art," director Thomas Kohler joked. The 150 years from the mid-to-late 19th century to the end of the 20th century were also Germany's most crucial historical period. The country's experiences during these 150 years are perhaps equivalent to the changes in other countries over millennia.

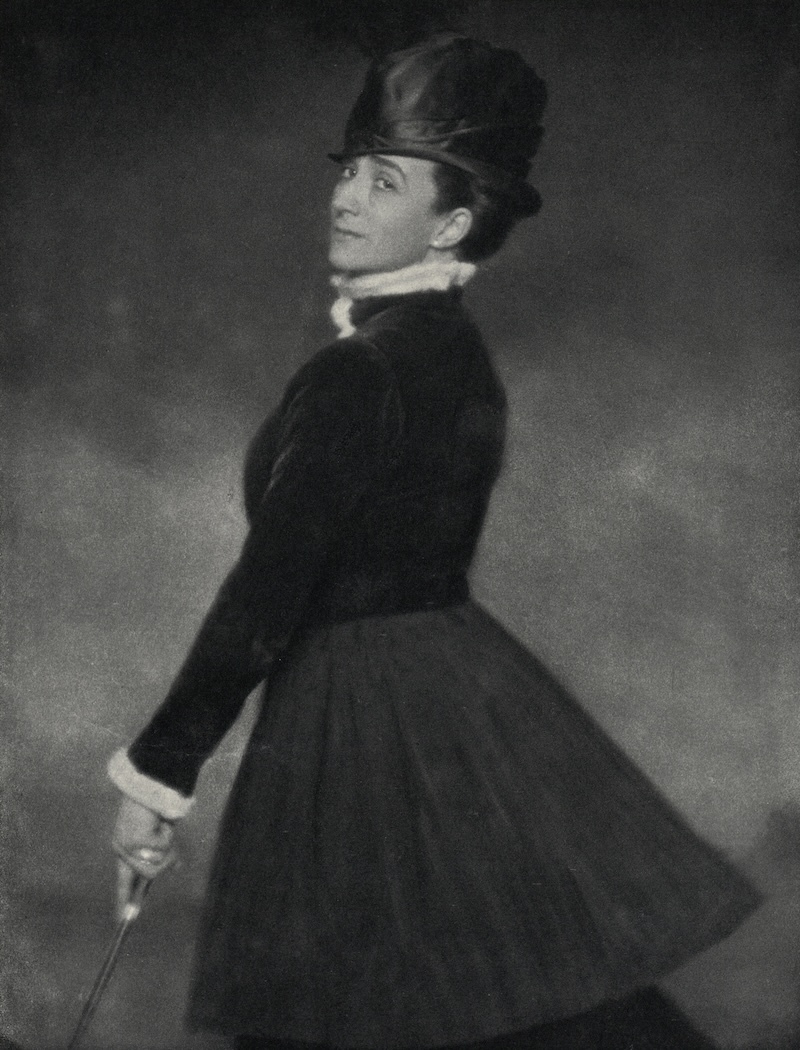

Jacob Hilsdorf's portrait of Anna-Muthesius, a representative of the Art Nouveau movement, 1911. (Berlinische Galerie)

"Don't be misled by the architecture," Thomas said. Many art museums are marked by famous buildings, but the Berlin Gallery is much more austere, embodying a distinctly German pragmatic spirit. "The space isn't perfect, but imperfection is our strength," Thomas said. "It allows us to interpret the infinity of art within a limited physical space."

True to German rigor, the curator's words were borne out upon entering the "Fitz Photography Exhibition." German art seems to eschew superficial propaganda, retaining only the hardcore essence. Viewers are naturally captivated by its sublime beauty, unable to look away. Within the Morandi-inspired exhibition space, the 100-year-old film photography gave me the pleasant surprise of discovering a treasure. The tiny film, the black-and-white images tinged with the yellow of time, transported me to a wondrous world I had never experienced before: Berlin during the Weimar Republic.

Fitz, Selfie, 1927. Courtesy of Berlinische Galerie

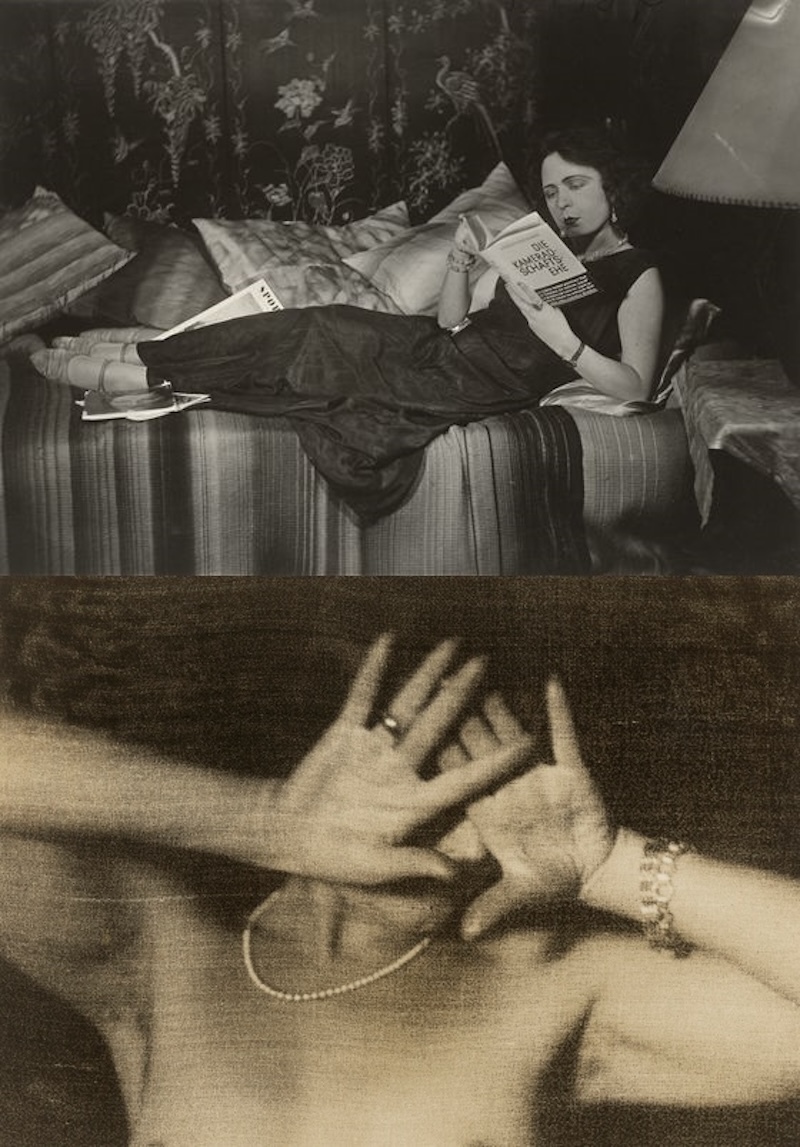

"Does it remind you of Cindy Sherman?" Thomas asked. I think the order should be reversed: Cindy Sherman reminds people of German photography. Sherman, the American artist often called the most expensive photographer, is considered the originator of the selfie—this is how contemporary art misrepresents art history. Because photographers like Fitz are largely overlooked, people don't realize the selfie existed a century ago. In today's world of fame and price, we mistakenly identify the most expensive photographers as the originators of the selfie.

Although she didn't attend the Bauhaus, Fitz was deeply imbued with its spirit. Born in 1901 in what is now Poland, she studied design at the Museum of Decorative Arts in Berlin and photography at the studio of Lutz Kloss. In 1927, at the age of 26, Fitz, a single woman, opened a studio in Berlin. During Berlin's turbulent Golden 1920s (Golden 1920s), she created a body of work comprised of self-portraits, nudes, dance, and experimentation. She was a photographer, director, and her own model.

Fitz and Harke, Self-Portrait, 1927. Courtesy of Berlinische Galerie

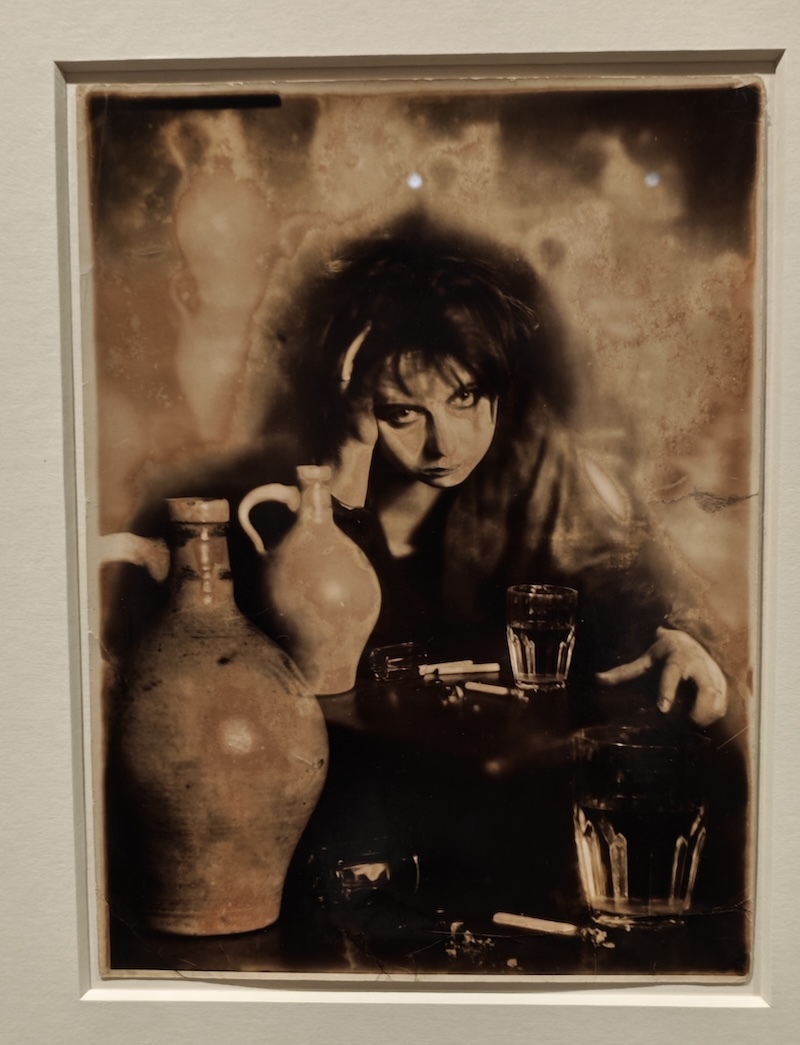

Fitts confidently wielded his camera to depict various Weimar Republic women in a humorous and satirical manner, subverting the stereotypes of traditional female roles. He also partnered with photographer Heinz Hajek Halke to use distortion, double exposure and shadow effects, combining masks, dramatic poses and grotesque elements to reflect loneliness, alcoholism and terror, combining private introspection with social issues, presenting a social realist style of photography, allowing viewers to gain insight into the various aspects of the Weimar Republic.

Fitts's avant-garde work also brought her a Bauhaus-like consequence: a ban by the Nazis. "After the Nazis came to power, her photography was deemed degenerate art and banned from exhibition. This was devastating for the photographer, and she never ventured into commercial photography again," Thomas explained. The breathtaking photographs in "The Fitts Photo Exhibition" are largely frozen in time, dating back to 1927. In 1943, Fitts' studio was destroyed in the war, leaving very few of her works.

Fitz, Poppies (Mohn), watercolor, 1942. Courtesy of Berlinische Galerie

What was Fitz doing after turning 32? Thomas led me to the final space of the photography exhibition and pointed out the answer: "She changed careers and became a watercolor teacher." Looking at the wall of watercolors, I entered the botanical garden surrounded by dahlias, lilies, roses, orchids, and poppies. Fitz painted 6,000 watercolors in the last 60 years of her life. These works, like botanical specimens, radiate a classicist luster, so different from her bold and avant-garde photography that they seem like the work of a different artist. Plants are so obedient, like true citizens: gentle, sensible, and uncomplaining.

When faced with severe setbacks in life, why not bow to reality and become a sycophant who guarantees a stable income? But this assumption underestimates Fitz. When I approached her watercolors, I discovered that plants are actually her "new nude models," their poses more flexible and beautiful than those of humans. Fitz's nude photography has the sinuous feeling of plant roots, and clothing is photographed like petals, with the human figure unfolding behind the fabric. In the years when she could not practice photography, Fitz found artistic sustenance in plants.

Berlin 1920: Disguise, Impersonation, and Cosplay

Weimar Germany spanned the 15 years between the end of World War I in 1918 and the rise of the Nazis in 1933. As a historical interlude between the two wars, Weimar Germany was plagued by rampant crime and bizarre phenomena. "All values had changed; not only material things, but also state laws were ridiculed; no moral norms were respected," Zweig wrote in The World of Yesterday. "Berlin was the Babylon of the world."

Dance halls (Kabarett) flourished in Weimar Germany, offering indulgent entertainment and becoming a haven for those traumatized by war. Author Klaus Mann wrote in The Turning Point: "The German capital cries out, 'I am Babylon,' an urban monster, with the most raucous and sinful nightlife. Don't miss this unparalleled performance! It's a Sodom and Gomorrah with Prussian rhythms, Berlin with its glamorous corruption."

Berlin dance halls in the 1920s

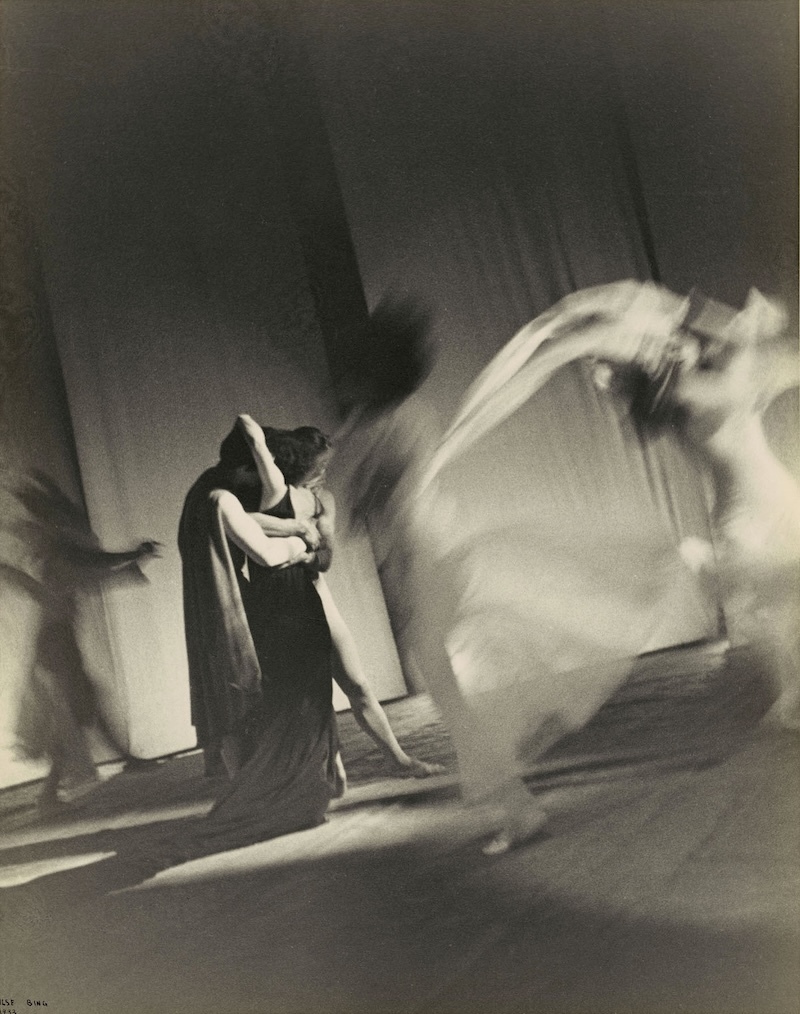

Fitz, The Dancer (Berlinische Galerie)

Kabarett cabaret was the most representative entertainment in Weimar Germany, characterized by political satire and black humor. It was almost entirely devoted to serious political and social themes, criticizing society with cynical satire techniques.

Fitts's nude photography was influenced by Berlin's ballroom culture, avant-garde modern dance, and particularly the Banana Dance, which was brought to Berlin by black dancer Joseph Baker in 1925. Fitts's stage performances focused on costumes and body movement, capturing not only the dancers' expressive poses but also trends in clothing and styling.

Self-portrait of Fitz, 1927. Photo: Berlinische Galerie

Through Byzantine-inspired costumes, Fitz impersonated others, becoming one of the earliest cosplay photographers. Combining white lace cutouts with dappled light and shadow, she created unique images. Dressed in Charleston skirts or glamorous gowns, with upturned bobs or wigs, her face mysteriously obscured by dappled veils, her features appearing and disappearing between the veil and the light. Her meticulously composed images explore the tensions between concealment and exposure, disguise and identity, playfully shifting between different femininities and styles.

Fitz, Selfie, 1927. Courtesy of Berlinische Galerie

Fritz Lang, still from Metropolis, Germany, 1927

Fitz was also a brilliant choreographer. In conversation with the camera, she struck poses, embodying her own concepts, creating enigmatic scenes with lace, brocade, and theatrical lighting, depicting bodies in motion. In 1927, as she twisted her arms, the legendary German film Metropolis was being released. Its complex, magical dance, bouncing in place, with its frenetic steps, resembled the Hindu goddess Kali's dance of death. Both Fritz Lang's films and Fitz's photographs are imbued with expressive tension, echoing the most distinctively German expressionist art.

Woman in a Bottle: Surreal Photography

If Impressionism is the symbol of French art, its polar opposite, Expressionism, is the hallmark of Germany. Impressionism is a glimpse of external reality from inner memory, while Expressionism is the outward expression, call, and roar of the inner soul.

Expressionism was closely tied to changes in German society. "The war had scarred the human soul, distorted and destroyed it completely. Crime had skyrocketed, and those returning from the war could no longer find their place in normal society," wrote German lawyer Erich Frey. "Berlin was already in a state of civil war," wrote Isherwood, the Berlin-based author of "Farewell, Berlin," in "Mr. Norris Changes Trains."

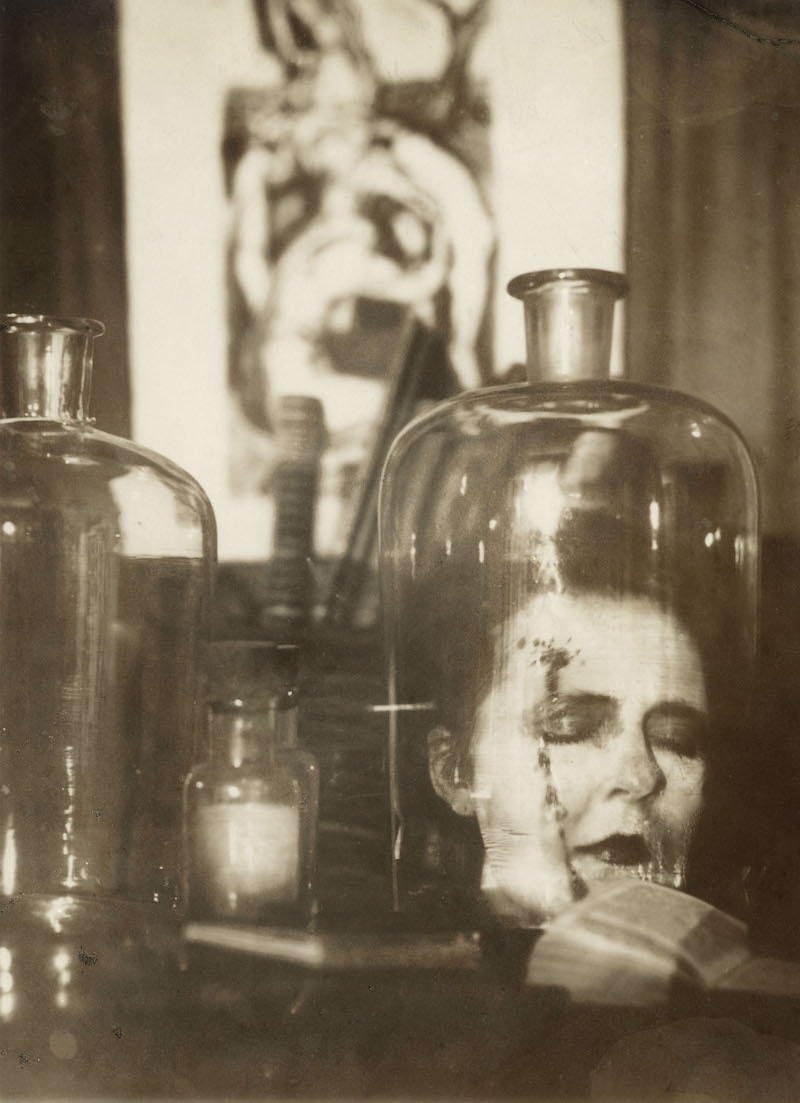

Fitz, Untitled, 1927. Courtesy of Berlinische Galerie

Fitts's photography, characterized by an expressionist style, uses overlapping images, compressed proportions, and special effects to depict human expressions, conveying fear, distortion, and psychological trauma, creating an atmosphere of dread and dislocation. The inverted heads and deliberately enlarged and reduced figures evoke the surveillance scenes in the novel "1984." The solemn men, with their stern features and dark circles around their eyes, appear elusive and vampire-like, while the women, huddled below them, appear oppressed, echoing the 1922 expressionist film "Nosferatu."

Top left and right: Fitz, Untitled, 1927. Photo by Laura Shen. Bottom: FW Murnau, still from Nosferatu, 1922, Germany.

In 1929, Woolf wrote in A Room of One’s Own: “The body is trapped in a fantastic glass house, the consciousness is completely isolated from the outside world, and it is free in a harmonious meditation.”

Fitz, Psychic Suicide, 1927. Courtesy of Berlinische Galerie

Fitz's "Selbstmord in Spiritus" is a mysterious and striking photograph, almost surreal. "There was very little oxygen left in the bottle," Fitz recalled taking the photo in 1992. "If I hadn't clicked the shutter, I would have suffocated and committed suicide."

Gustav Klimt, Judith with the Head of Holofernes, 1901 and 1909

Pabst, still from Pandora's Box, Germany, 1929

Fitz's head, in its near-death state, forms an interesting contrast with Klimt's "Head of Judith and Holofernes" and the contemporary German New Objectivity masterpiece "Pandora's Box" (Die Büchse der Pandora). While "Head of Judith and Holofernes" depicts the Vienna Secession's depiction of female power and its triumph over male castration, "Pandora's Box" creates a sense of terror and threat through sexual innuendo. In Fitz's expressionistic suicide, the woman's expression remains calm, devoid of pain.

Bauhaus and Modern German Photography

After 60 years of obscurity, Fitz resurfaced in the art world in 1990. "It all started with a 1990 photography exhibition," Thomas recalls. "Fitz's former partner, Halke, left two photos with Fitz's name printed on the back for the gallery's then-director of photography, Janos Frecot. We tried asking friends in the photography world about her, but no one had heard of her."

If not for a miraculous opportunity, Fitz would have been forever buried in the ashes of time. "An art student in Fitz's painting class contacted us and suggested we try Nienhagen in Lower Saxony." After speaking with Fitz, the Berlin gallery initiated the "meeting of the century" with Fitz.

Fitz, Untitled, 1927. Photo: Laura Shen

Fitz, Untitled, 1930. Courtesy of Berlinische Galerie

At the time of this late meeting, which came 60 years later, Fitz was already 89 years old. “There were very few of her works left, but I knew that I was in front of an extraordinary master,” recalled Janos Frecot, then director of photography at the Berlin Gallery.

Under Nazi oppression, Fitz gave up photography. She described her marriage to her husband as "a mutually beneficial expedient (German: Vernunftehe) in a dark time." In the years that followed, Fitz remained an unknown art teacher. Even as late as 1982, her only known work was for charity. She provided drawing tutoring to Jewish children and youth during the Nazi era, for which she was awarded the Bundesverdienskreuz ("Hospitality Award") by the Federal Republic of Germany.

Arndt, Masken selbstbildnis (Self-portrait with a Veil), 1930, Museum Folkwang, Essen, Germany

Like many Bauhaus photographers, Fitz is an overlooked artist, yet also a creator whose work is recorded in the history of modern German photography. His contemporaries include Marianne Breslauer, Lotte Jacobi, Gertrud Arndt, avant-garde commercial photographer Ilse Bing, New Visual Wave representative Germaine Krull, and Lucia Moholy of the Bauhaus.

Ilse Bing, Ballet, photography

German photography played a milestone role in the history of modern photography, yet its importance has been underestimated. In 1717, German Johann Heinrich Schulze invented photography by using a photosensitive paste to capture images of letters. The obscurity of modern German photography stems from historical factors: Bauhaus photography was declared "degenerate art" by the Nazis and banned. Later, Allied bombing during World War II destroyed many of Schulze's works, effectively obscuring their existence. Furthermore, a number of Germany's best photographers left Germany due to the war and were forced to work as foreigners. Lotta Jacobi, Ilse Bing, and Ellen Auerbach are considered "American photographers." Others include Crowe, who lived in France, the Netherlands, and Thailand; Lucia Moholy, who lived in the UK and Switzerland; and Grete Stern, who moved to Argentina.

A 1910 portrait of Italian actress Maria Carmi by Austro-Hungarian photographer Karl Schenker, from the Berlin Gallery

In recent years, the Berlin Gallery has fostered a rediscovery and re-examination of German photography. In addition to establishing a photography department dedicated to collecting vintage photographs from the late 19th century onwards, the Berlin Gallery also held a special exhibition, "Portraits of Women in the 1920s." In 2021-2022, thanks to the Berlin Gallery's efforts, Martha Fitz's 1927 selfie was loaned to the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York and the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C., as part of the exhibition "The New Woman Behind the Lens." Of the 189 photographs included in the exhibition, nearly half were by German or German-speaking photographers, allowing a wider audience to understand Germany's significance in initiating modern photography.

No one believed Fitz would be discovered 60 years later, just as no one believed the Berlin Wall would fall. From 1933 to 1990, Nazism, World War II, and the division of East and West Germany followed one after another. Fitz's photography, buried like a shadow, silently said "no" to this dark era. One cannot choose one's era or country, but one can choose the attitude with which one faces it. Fitz responded to fate's relentless blows by persevering in watercolor painting and art education, and with 60 years of tenacious vitality, he reached the day in 1990 when fate struck him. In 1990, the year East and West Germany dramatically unified, Fitz opened his home to welcome the visiting Berlin Gallery team. As Germany ushered in reunification, the dawn of art once again shone upon Fitz's face. In 1994, four years after being rediscovered by the Berlin Gallery, Fitz passed away at the age of 92.

"Performances of the Self: A Retrospective of Martha Fitz" features over 140 works and will be on view at the Berlin Gallery from July 11 to October 13, 2025.