In the early 1920s, what possibilities did photography hold for a modern art form? From household utensils to people, artist Man Ray viewed everything he saw as an object for aesthetic creation. A series of rayographs, part of the recent "Man Ray" exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, illustrates how he "worked with light itself." The exhibition also features the most expensive photograph ever sold at auction: "Ingres's Violin."

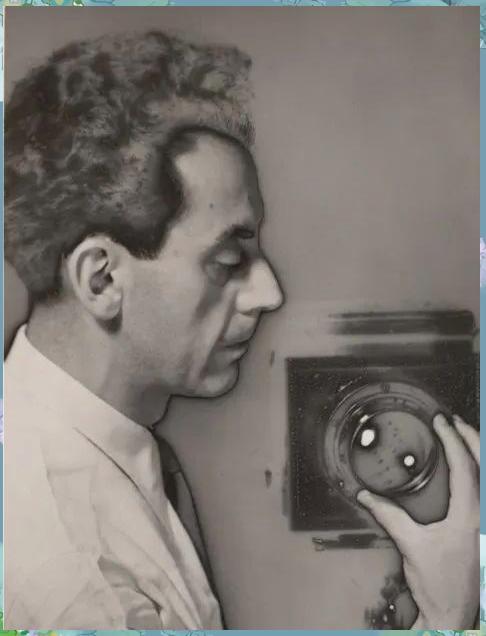

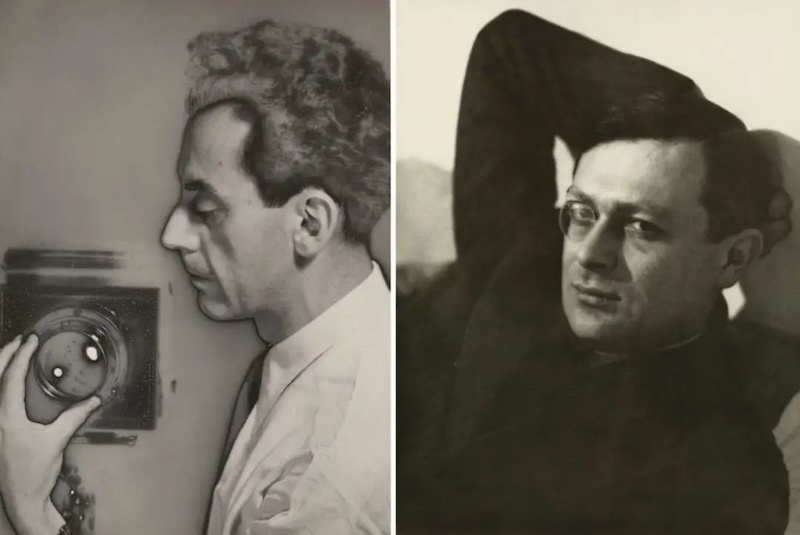

Man Ray (1890-1976) self-portrait

Man Ray (1890-1976), an American Dada and Surrealist artist, was proficient in painting, film, photography, etc., but he was the first artist in history whose photographic works were worth far more than other art forms he was good at.

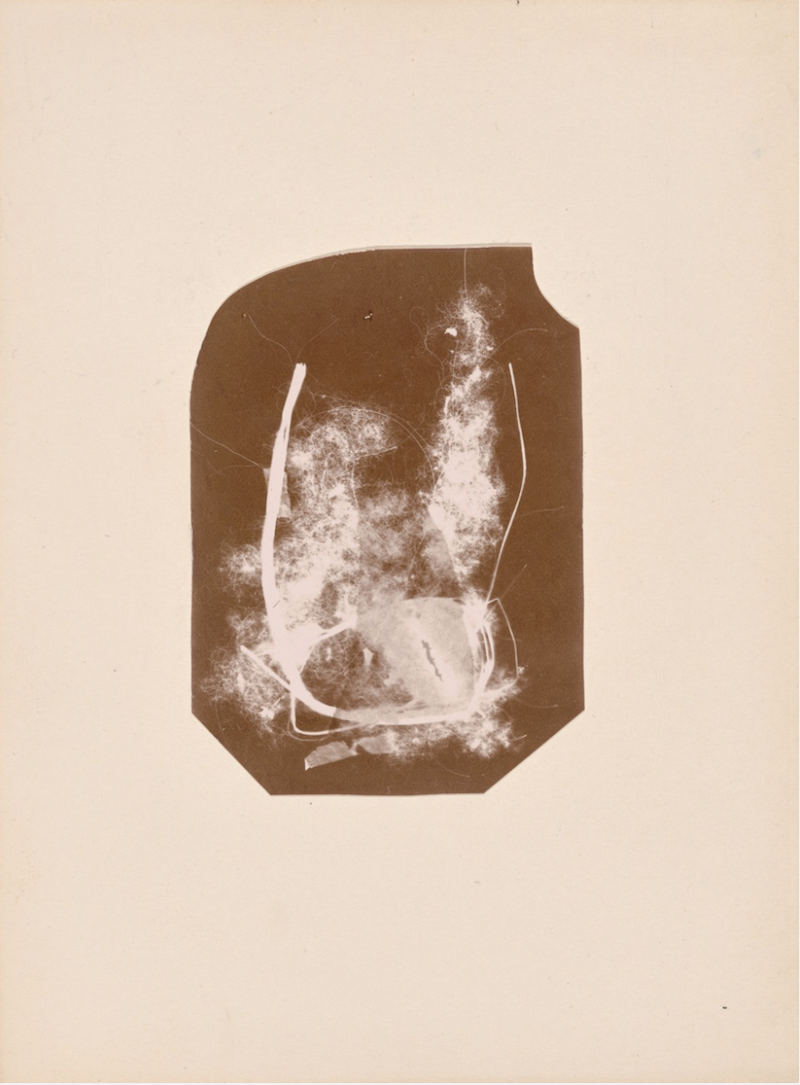

In the winter of 1921, Man Ray moved from New York to Paris, where he worked as a painter and made a living as a photographer. One evening, he placed a funnel and thermometer on a piece of unexposed photographic paper, which accidentally fell into the developing tray of his darkroom. He turned on the light, and a ghostly image appeared on the paper. He quickly abandoned the fashion photos he was preparing, having discovered a new photographic method he called "rayographs."

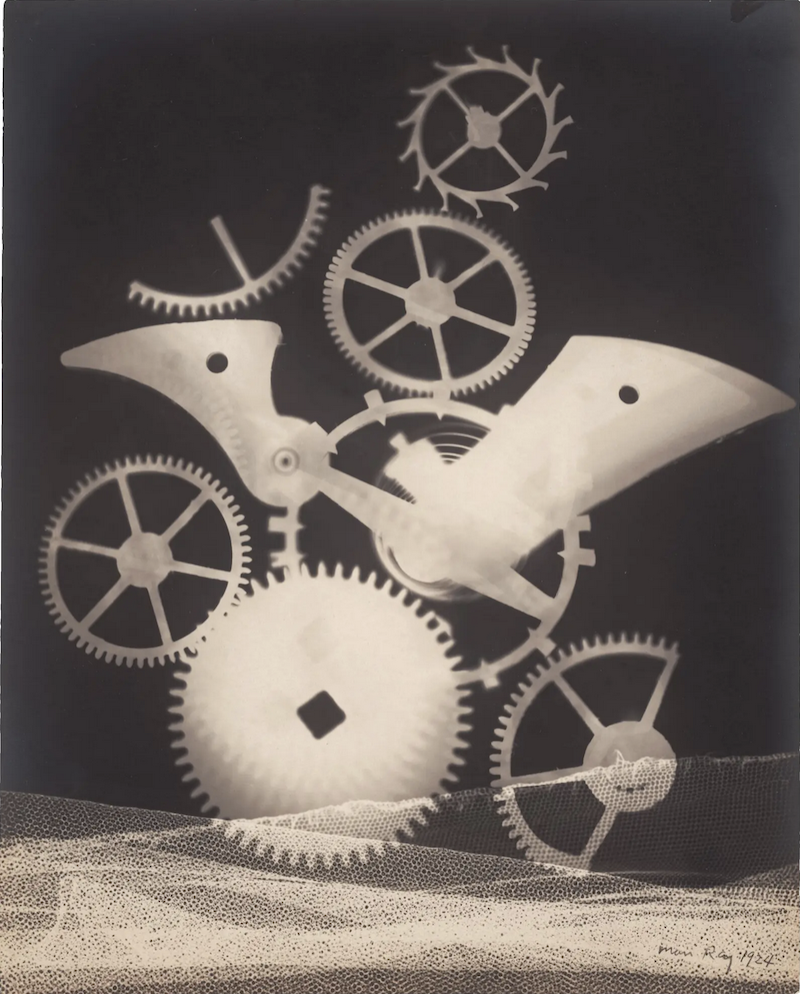

Man Ray, “Rayograph” series, 1924, created without a camera

At least, that's the story Man Ray tells. Recently, the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York opened the exhibition "When Objects Dream." Curators Stephanie D'Alessandro and Stephen C. Pinson attempted to uncover the legend surrounding Man Ray. Many of the stories about Man Ray were woven by the artist himself, and some mysteries remain unsolved. "We've spent years researching this issue, bringing in many experts and conservators," D'Alessandro said, "but there are still many unsolved mysteries. That's the charm of his work."

Curators have brought together 64 of Man Ray's rayographs, created during the artist's most illustrious period, the late 1910s and 1920s, along with approximately 100 other works, including films and objects. They argue that despite their relatively brief presence in the artist's oeuvre, these rayographs offer a key to understanding his diverse and prolific career.

Man Ray, “Rayograph” series, 1922

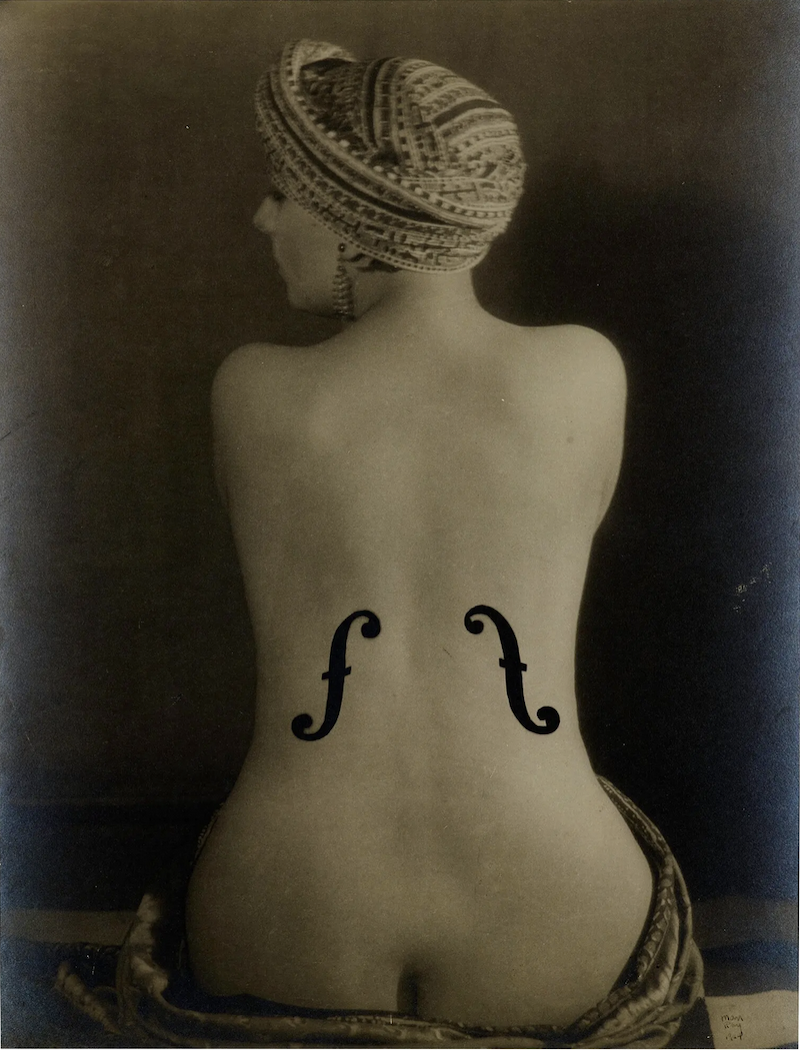

Approximately one-fifth of the photographs on display come from an unannounced pledge by John Pritzker, a museum trustee, private equity investor, and heir to the Hyatt Hotels Corporation. Pritzker donated 188 works by Man Ray and his Dada and Surrealist followers, including Marcel Duchamp, Francis Picabia, and Max Ernst. The most notable of these is the most expensive photograph ever sold at auction: "Le Violon d'Ingres." This photograph, taken by Man Ray of his lover, Kiki de Montparnasse (born Alice Prinn), was purchased by Pritzker at Christie's New York in 2022 for $12.4 million.

Man Ray's "Ingres's Violin," 1924. This work, which sold at auction for approximately $12.4 million, features Man Ray's lover, Kiki de Montparnasse (born Alice Prinn).

Pritzker said that before acquiring Man Ray's work, he had been buying "beautiful photographs" by photographers like Imogen Cunningham and Edward Weston. In 1997, he bought his first Man Ray work, a shadow print of a shaving brush and candle, which is also on display in the exhibition. Pritzker said, "It's not so much the photograph itself as it is about what he was doing and what he must have been thinking at the time. I was so fascinated by Man Ray that I later became fascinated by a community of writers and artists." Pritzker's donation also funded an art institute dedicated to Dadaism and Surrealism.

Man Ray rediscovered the photogrammetric technique, not invented it. Since the dawn of photography, people have been placing objects on light-sensitive paper to create images without a camera. These photographs, often called photograms, were created in the 1830s by William Henry Fox Talbot, one of the pioneers of photography. A few years later, his friend Anna Atkins produced similar images.

Christian Schade, “Schade Photography”

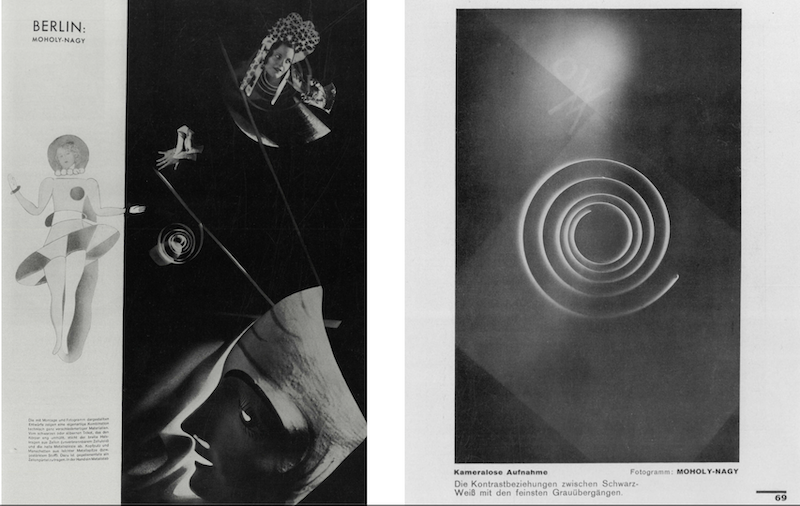

In Man Ray's time, the modernist Christian Schad had already explored photography. In fact, Dadaist artist and promoter Tristan Tzara stayed in the same hotel as his friend Man Ray and owned a collection of photographs he called "schadographs," so Man Ray likely viewed these photographs before creating his first schadograph. A year later, Hungarian artist László Moholy-Nagy began creating schadographs. Like Man Ray, these artists applied the technique to abstract compositions.

Left: Man Ray, Self-Portrait with Camera, 1931. Right: Man Ray, Tristan Tessara.

Photographic works by Hungarian artist Laszlo Moholy-Nagy

Yet, Man Ray brought his creativity and rigor to every new genre he ventured into. Born Emmanuel Radnitzky in 1890, Man Ray grew up in Brooklyn before reinventing himself as an artist in New York. Before moving to Paris, he tirelessly explored how to use shape, color, and texture to bring the flat surface of a painting to life. He churned out ideas, but he refused to view brushes and paint as mere means to an end.

Through object projection, he adapted old techniques to new ones. One of the highlights of the exhibition is the ability to compare the old and new works. Man Ray once said that arranging objects on photosensitive paper was like cutting and assembling shapes to create a collage. The exhibition also includes a more direct translation: a set of hand-colored stencil prints, "Revolving Doors," from 1926, which recreate a collage series he created a decade earlier.

Man Ray, The Man, 1918-1920

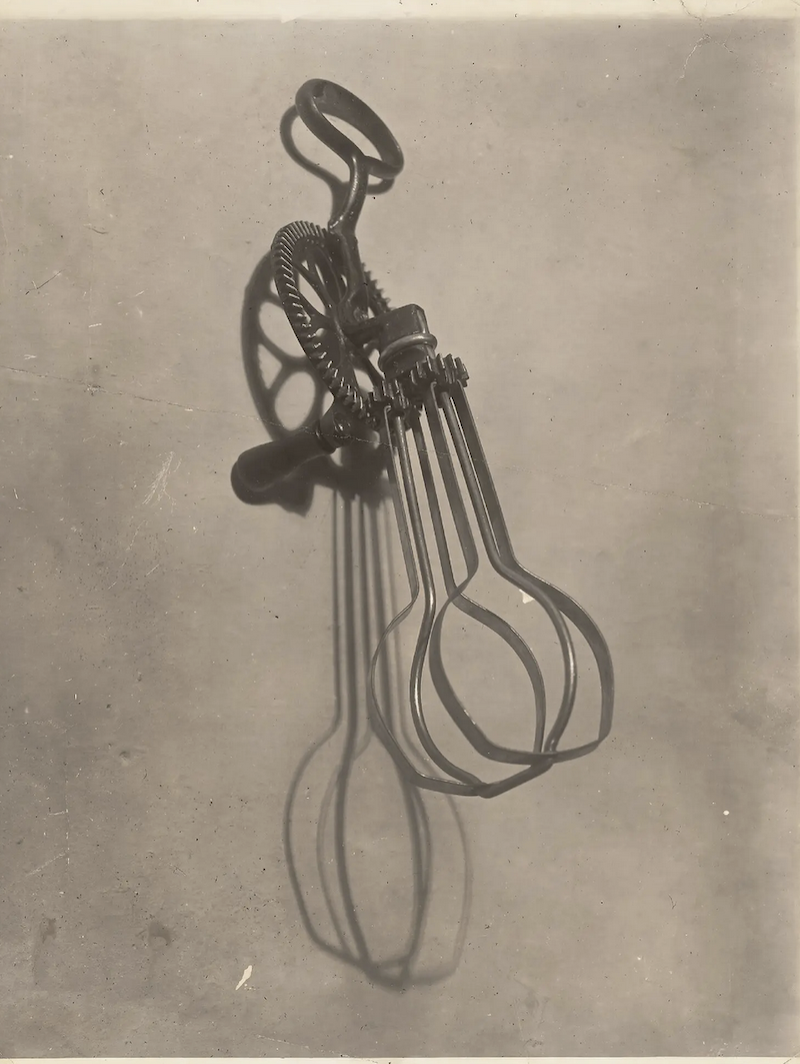

In photogrammetry, blur and varying translucency are created by raising and lowering an object, similar to moving a spray gun across a canvas. This technique uses pressurized aerosol spray. Before photogrammetry, Man Ray used everyday objects to create melancholic and mysterious photographs. For example, he lit an egg beater, casting a shadow, and called it "Man." This was a random title, as he later inscribed a print as "Woman."

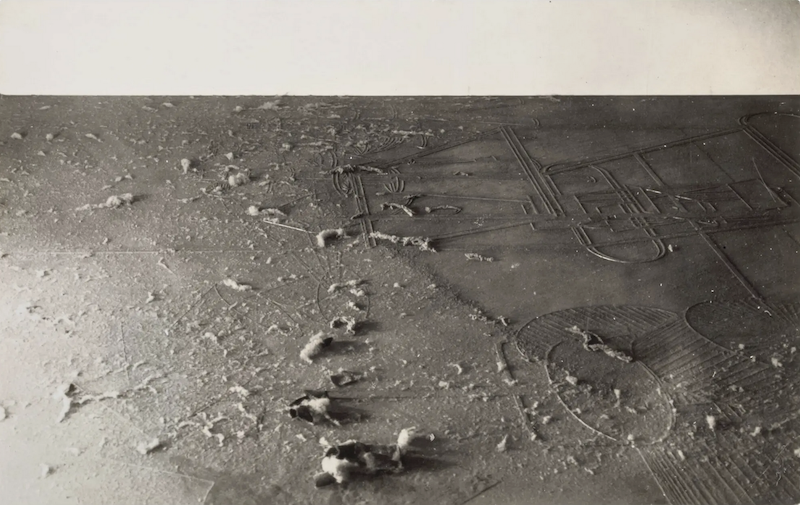

He also explored the continuity of time and the shifting of scale. For example, he focused on a small section of Duchamp's work-in-progress, "The Bride Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors, Even (The Large Glass)," and held his camera's aperture open for hours in dim light, recording the dust that accumulated on the glass. This close-up, titled "Dust Breeding," resembles a bird's-eye view of an arid landscape.

Man Ray, The Dust, 1920

In the months following his discovery of his new method in the darkroom, Man Ray toiled relentlessly, producing as many as 100 photograms in 1922. In April of that year, he wrote to his American patron, Ferdinand Howald, “In my new work I feel that I have reached the culmination of what I have been striving for during the past ten years.” He added gleefully, “I have at last left the sticky medium of oil paint and begun to work with light.”

Although Howald dismissed these works, his fellow artists in Paris raved about them. For practitioners of Dadaism and its successor, Surrealism, irrational juxtapositions and the subconscious were the source of art. In praising these works, Tzara wrote, "The objects, cast in a soft light, assume a surprising transparency, a sense of a dream within a dream." For Jean Cocteau, they challenged the dominance of painting. The magic of shadowworks lies in the way everyday objects remain legible yet become strange and otherworldly. Through the artist's masterful use of light, shadow, and gradations of gray and black, they take on a whole new dimension.

Man Ray was so fascinated by the technique of projection that he briefly gave up painting. It wasn't until 1923 that he began creating projections of his paintings using a palette knife on inexpensive drawing boards, sandpaper, and wood. His artistic output was vibrant. He also experimented with the so-called "exposure technique," another known technique he claimed to have discovered by accident.

Man Ray, Portrait of Lee Miller, 1929

Man Ray's studio companion and lover at the time, Lee Miller, first accidentally created a solarization work in 1929. The curator believes that the solarization, with its dark outlines of the subject against a gray background, continues Man Ray's lifelong ethos: he viewed everything he saw, from household utensils to people, as objects to be aesthetically manipulated.

Man Ray, “Rayograph” series, 1922

André Breton, known as the "Pope of Surrealism," wrote in 1927 that the women who posed for Man Ray were to him the same way as "a quartz gun, a bunch of keys, hoarfrost, or a fern" in his light-and-shadow photographs. Breton was probably referring to "Ingres's violin," a French title referring to a hobby, inspired by the story of the great painter Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres, who cherished his amateur violin playing as an art form.

For this photograph, Man Ray photographed Kiki de Montparnasse from behind, naked from the waist down and wearing a headscarf. The same pose appears in Ingres's painting "Bathers of Valpinçon" (now in the Louvre). In the photograph, Man Ray outlined the sound holes of a violin in black ink, just below Kiki's waist.

Ingres's painting "Bathers at Valpinçon" (now in the Louvre)

Later, he had a new inspiration. He enlarged "Kiki" in the darkroom and covered it with a piece of cardboard with two sound holes cut out. Then, he used light again to burn the pattern black, creating what he called "a combination of photograph and object shadow."

Man Ray produced multiple copies of this unique hybrid negative. Beyond his masterful fusion of techniques, he also transformed a literal pun into visual reality. With its beauty and absurdity, "Ingres's Violin" embodies the unique wisdom of Surrealism beneath its nonchalant nature more than any other work of art. Furthermore, Man Ray's ingenuity and technical virtuosity are evident in this exhibition.

The exhibition will run until February 1, 2026.