From 1943 to 1945, oil painter and art educator Dong Xiwen (1914-1973) lived and worked in Dunhuang for more than two years, a period that became an indispensable and important chapter in his life, profoundly influencing both his personal life and his painting. In the years that followed, he spoke of Dunhuang many times, expressing both感慨 (gǎnkǎi, deep feelings) about the vicissitudes of the past and his evaluation of the Dunhuang Grottoes. The author of this article, Chen Derong, Dong Xiwen's niece, recently wrote an article on understanding the impact of her trip to Dunhuang on Dong Xiwen, which was published in the art section of The Paper.

one

The discovery of the Library Cave in the Mogao Caves of Dunhuang in 1900 was a landmark event in the world of archaeology. Since its discovery, it has attracted the attention of scholars from many countries. In 1942, at the height of the War of Resistance against Japan, the Nationalist government established the "National Dunhuang Art Research Institute" in Dunhuang, determined to carry out conservation and research work. This initiative attracted a group of interested and dedicated researchers and artists to Dunhuang to conduct research, including Dong Xiwen.

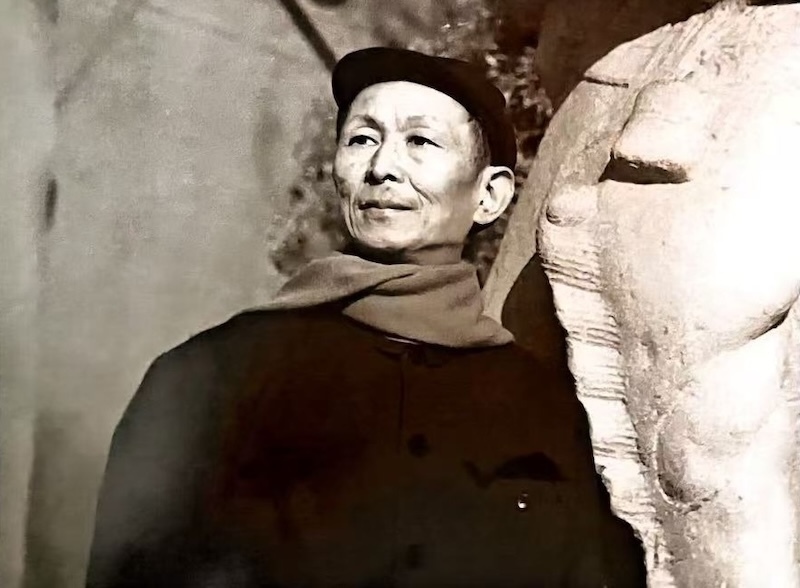

Dong Xiwen (1914-1973)

In 1942, Dong saw Chang Shuhong's Dunhuang copies exhibited at the Chongqing Academy of Fine Arts and was "deeply moved by the charm of Dunhuang art." He immediately wrote to Chang Shuhong, expressing his desire to visit the Mogao Caves. Chang was the head of the research institute. Before this, Dong had always longed to study in France and had studied at the "Paris Academy of Fine Arts Branch" in Hanoi, Vietnam, in preparation for his studies in France. However, this avenue was cut off due to the outbreak of the War of Resistance against Japan. Dong remembered his father saying, "Since Xiwen cannot go to France for further studies, going to Dunhuang is another option. I hope he can draw nourishment from this art treasure and forge his own artistic path." At that time, Dong was in his thirties, full of ambition as he embarked on his life's journey.

Material conditions in Northwest China were very poor in those days, and Dong's experience in Dunhuang was extremely arduous. He and his newlywed wife, Zhang Linying, endured a three-month trek, traveling by truck, donkey, and camel in turn, to reach Dunhuang. Recalling that time, he said, "For two and a half long years, I reduced my material life to the bare minimum, immersing my entire soul in the embrace of the ancients. The lonely environment and simple work made me naturally forget where I came from." Although life was difficult, he had deeply integrated himself into the atmosphere of religion and religious art, which provided him with special spiritual enlightenment. He often imagined in the caves the splendor created by hundreds of candles lit and anonymous painters pouring their hearts and souls into their works. He was also deeply moved by the spirit of forbearance and self-sacrifice for the salvation of all beings, embodied in Buddhist tales originating from folklore.

In 1943, Dong Xiwen and Zhang Linying married in Chongqing.

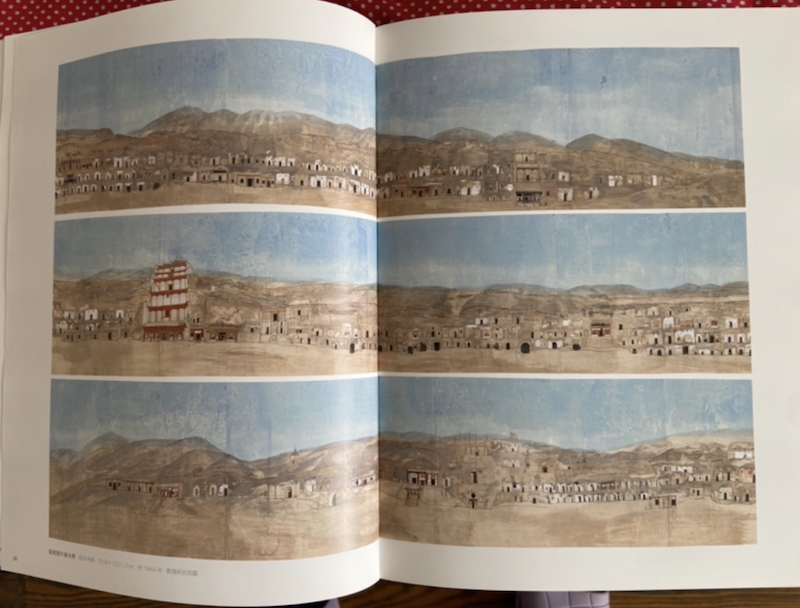

In 2014, on the centenary of Dong Xiwen's birth, his sketch scroll "Panoramic View of the Outer Cliff of Mogao Grottoes," depicting the exterior of the Mogao Grottoes, was exhibited. Painted between 1943 and 1945, the 12-meter-long scroll (70.8 x 1221.7 cm) portrays a magnificent kilometer-long stretch of Thousand Buddha Caves in the desert. Hundreds of grottoes are visible on the continuous, yellowish-brown hills, some very simple with only a few strokes, others quite ornate. The multi-story buildings of the Mogao Grottoes are particularly striking. Standing there, I was deeply moved by the scene; the desert and countless grottoes merged into one, conveying the power of time and space, and the strength of religious faith. It's not hard to imagine Dong's feelings when he painted it. When I visited Dunhuang in the 1990s, this landscape was no longer visible; the changes since then are even more significant.

Dong Xiwen's "Panoramic View of the Outer Cliffs of Mogao Grottoes"

In these Buddhist sites, Dong and his colleagues conducted research and copying work. Over two years, they completed a series of copies, surveys, records, and investigations, and published the book "Inscriptions on the Images in the Dunhuang Grottoes." Clearly, they not only focused on the artistic features of the grottoes but also sought to understand their development history, Buddhist concepts, and stories. In the 1960s, Dong commented on this period of work: "During the War of Resistance Against Japan, although I lived here for a time, research work had not yet fully commenced. Besides personal copying, deeper research into Buddhist art and interpretations of sutra illustrations were insufficient… Past research had devoted considerable effort to textual criticism of sutra meanings, but artistic aspects were almost entirely lacking."

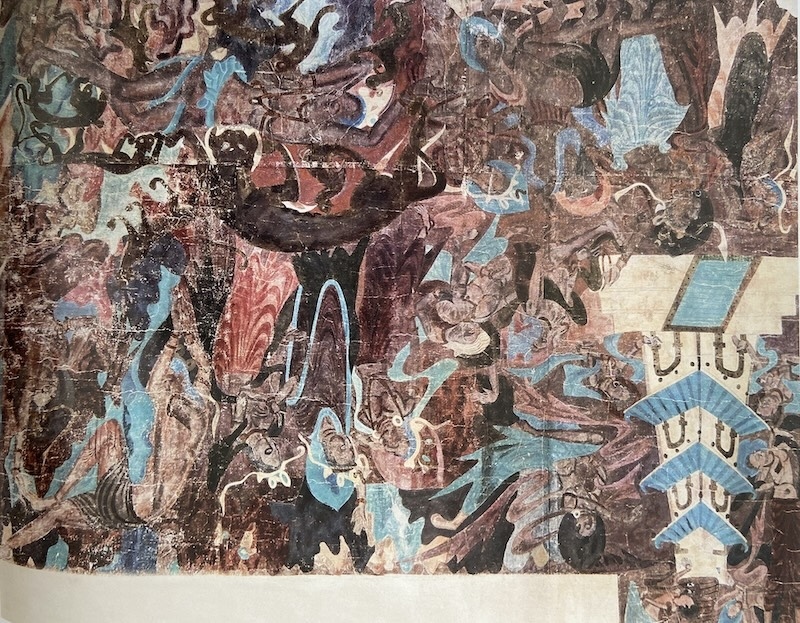

Dong made extensive copies and creations of the Dunhuang murals, leaving behind a number of artistic masterpieces. He "particularly loved and chose to copy large-scale murals with complex plots and grand scenes," the most famous being his copy of the Northern Wei Dynasty's "Jataka of Prince Sattva," in which the "Sacrifice to Feed the Tiger" scene depicts Prince Sattva encountering a hungry tiger during his travels. He wounded his own body and jumped off a cliff, offering his blood and flesh to the tigers. The painting, with its "rich and somber colors exuding a strong tragic atmosphere," expresses an extreme spirit of self-sacrifice, which is absent in traditional Chinese culture. This story deeply moved Dong and his colleagues. Chang Shuhong once said, "If Prince Sattva could sacrifice himself to feed the tiger, why can't I abandon everything to serve art and this great treasure trove of national art?" Dong also copied other early Dunhuang murals such as "The Jataka of the Deer" and "The Story of the Eye-Gathering Forest," which are rich in Western Region colors and styles. It is said that the painters may have come from India or the Western Regions, and Dong clearly intended to absorb their essence. He also attempted to restore the original colors of the murals and recreate the authentic scene, making it a valuable exploratory endeavor.

A Century-Long Retrospective of Dong Xiwen's Art

In 1944, their first son, named "Shabei," was born in a clinic in Dunhuang. A precious treasure of the desert, he became the crystallization of their life during their Dunhuang journey. When I last saw Shabei in 2024, he also recalled his birth with great emotion and encouraged me to write about his father's life. After the victory of the War of Resistance against Japan in 1945, Dong Xiwen and his wife decided to leave Dunhuang and return to the interior to begin new artistic explorations. In 1946, they held the "Dong Xiwen Dunhuang Mural Copying and Creation Exhibition" in Lanzhou, which was well-received. That same year, their second son, "Shalei," was born—a thunderclap in the desert. Both brothers are precious memories of the desert. Shabei passed away in 2025; this article is dedicated to him.

In 1948, Dong Xiwen was with his wife and two sons.

two

In 1960, Dong Xiwen led students from the Central Academy of Fine Arts back to Dunhuang. Revisiting the place evoked many emotions, but he also felt obligated to tell his students the story of Dunhuang. In that era of strong ideology, how should he evaluate the Dunhuang Grottoes?

Regarding the historical value of the Dunhuang Grottoes, Dong believes that the Thousand Buddha Caves, which have spanned thousands of years, are "the first treasure trove of China's rich artistic heritage." This is because "very few Chinese artworks from the Sui and Tang dynasties and earlier have survived," while "the Thousand Buddha Caves contain a large number of systematic murals and sculptures from the Wei, Jin, Sui, Tang, Five Dynasties, Song, Yuan, and Qing dynasties." In particular, "the main achievements of Dunhuang art predate the Yuan dynasty, much earlier than the Renaissance," thus possessing "high historical value" and being "especially precious material for the study of ancient Chinese painting." At the same time, Dong said, "The Mogao Caves represent an important stage in the development of Chinese art—the stage of religious art development. From it, we can see the introduction, evolution, and development of religious art, and we can see the general outline of the development of Chinese art." He listed the contents of the Dunhuang Library Cave, which contained more than 50,000 scrolls from the Northern Wei Dynasty to the early Song Dynasty. "It contains valuable materials on the history and literature of feudal society from the 5th to the 10th centuries," he said. "These mainly include Buddhist scriptures, Taoist paintings, documents, scrolls, silk banners, embroidered Buddha statues, bronze statues, etc. Among these cultural relics, some books are printed and some are handwritten, especially those from the Six Dynasties. The contents include geographical records, literary novels, popular poems, official documents, files, bills, etc. These documents are extremely important materials for the study of religion, politics, economics, and literature. The discovered scriptures include Chinese, Tibetan, Hindi, Mongolian, Kangju, and Uyghur languages." He spoke indignantly about the history of Dunhuang cultural relics being stolen by foreigners.

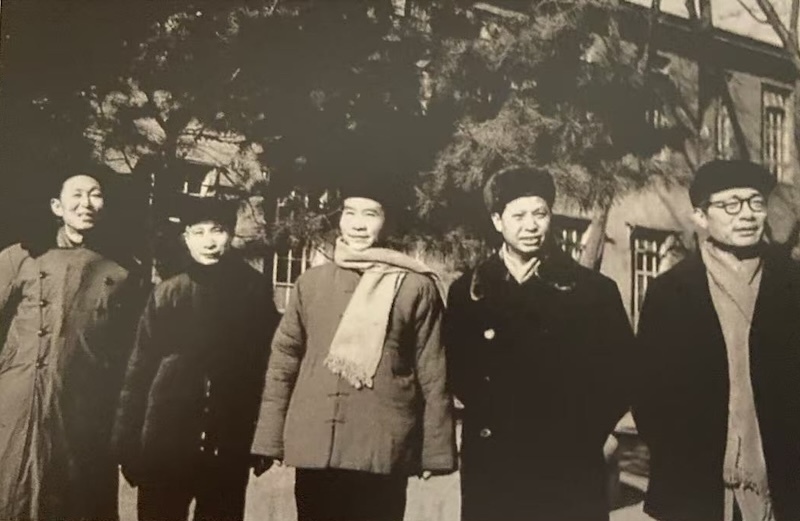

In 1962, Dong Xiwen posed for a group photo with Xu Xingzhi, Wu Zuoren, Luo Gongliu, and Ai Zhongxin on the campus of the Central Academy of Fine Arts.

To further illustrate the historical value of Dunhuang, Dong cited historical figures from the Dunhuang murals, such as "Zhang Qian's Journey," "Zhang Yichao's Journey," and "Lady Song's Journey," as well as numerous donor portraits, including emperors, nobles, high-ranking officials, commoners, servants, and prostitutes. He also mentioned the "Panoramic Map of Mount Wutai," a map depicting the route from Taiyuan to Mount Wutai and then to Zhengzhou, which he considered "the earliest and largest extant map."

In his lectures, Dong meticulously recounted the relationship between the evolution of the Dunhuang regime and the continued development of Buddhism in the region. He began by mentioning the time when the Xiongnu ruled Dunhuang, stating that "the Thousand Buddha Caves were built in the 2nd century BC, when Dunhuang was still under Xiongnu control." This differs from the current view that the Dunhuang Grottoes were first created during the Former Qin Dynasty (366 AD), indicating a significant time gap between the two periods. In fact, it is highly likely that Buddhism entered China in a folk form as early as before the Common Era, and the claim that it originated in the Former Qin Dynasty is merely based on recorded evidence; Dong's perspective offers a more historically insightful view.

Dong Xiwen's copies of Dunhuang murals

Dong emphasized that "from the perspective of the history of Sino-Western communication, China had no maritime trade with foreign countries before... Although this route was difficult, it was the only one." He added that "Dunhuang was the central point of the Silk Road at that time." Buddhism was introduced to China "with Dunhuang as its landing point." It can be seen that the role of the Silk Road was not only the exchange of material wealth, but also a channel for the exchange of spiritual culture. The spread of Buddhism to the East was due to the opening of the Silk Road.

three

When discussing his most important topic—the artistic value of Dunhuang art—Dong Xiwen devoted considerable space to repeated arguments, striving to both maintain a firm stance and affirm the value of religious art. His painstaking efforts are evident in his writing. To distinguish between religious and non-religious realms, he differentiated many concepts, such as the difference between religion and religious art, Buddhist doctrine and Buddhist narrative paintings, and religious doctrine and folk tales. At its core, he affirmed the existence of populist and realistic expressive techniques within Buddhist art.

When discussing religious beliefs, he believed that the goals of rulers and the ruled were different, and that the Buddha's own stories, many of which were educational.

Dong Xiwen's copies of Dunhuang murals

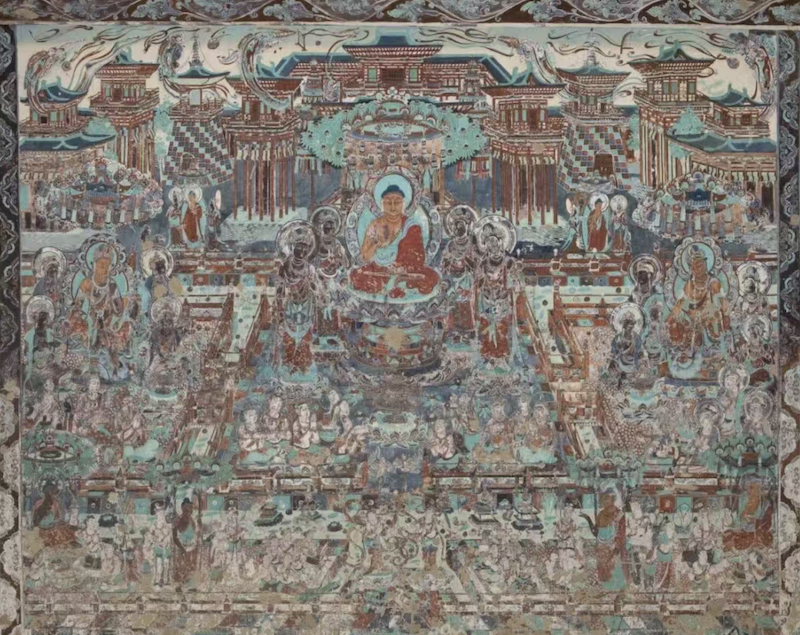

Dong Yuan gave a positive evaluation of the Pure Land School, considering it "a major school of Buddhism in China, unique in its Buddhist philosophical thought, and more in line with the thoughts, feelings, and needs of ordinary Chinese people." He noted that "India emphasizes profound religious philosophy, while the Chinese Pure Land School only requires belief in Amitabha Buddha to enter the Western Paradise," and that "the emergence of the Pure Land School reflects the feelings of the working people to some extent, and expresses their imagination in paintings," such as the pursuit of happiness in the *Parable of the Illusory City*. In an era that rejected the value of Buddhism, Dong Yuan's affirmation of a particular school of Buddhism and its connection to the needs of ordinary people is truly remarkable. Further research is needed in the 1980s when Japanese scholars studied the different attitudes of Chinese and Japanese Buddhists towards the Pure Land School's guidance of believers to the Western Paradise and the process of life transformation, namely "lotus rebirth," reflecting the cultural gap between China and Japan.

The art of the Dunhuang Grottoes can be categorized into three types: grotto architecture, murals, and painted sculptures. Dong's evaluation focuses on the murals, neglecting to discuss the painted sculptures of Buddha statues, clearly avoiding the issue of Buddhist imagery itself.

In his lectures, Dong covered every type of Buddhist narrative painting, clearly demonstrating his in-depth research into the content of the Dunhuang murals. He attempted to discover their inherent meaning and value, and to identify elements in each type of narrative painting that could be learned from and appreciated. As for why these Buddhist scriptures were chosen and transformed into narrative paintings, that is a complex issue of religious history and society, which Dong did not address, and which has been rarely discussed in domestic literature to this day.

Dong highly praised the role of the painters, believing that Buddhist narrative paintings were created by ordinary painters and expressed their intentions: "How to choose a subject, express the content, interpret the theme, and portray the character and qualities of people is a matter of great importance. It reflects their worldview, philosophy of life, aesthetics, and their own stance and viewpoints. Therefore, Buddhist art and the meaning of the scriptures differ greatly, and they are very different in nature." He believed that these painters were the ones who truly understood the Buddhist scriptures: "Painters who have dedicated their lives to this profession truly understand the Buddhist scriptures and often explore aspects they find interesting." He observed that "the painters of the Thousand Buddha Caves often focused on a few specific themes, and often depicted them very realistically, reflecting the painters' thoughts and feelings... When painters touched upon content related to reality, they explored it with great relish, as if they had found liberation from the constraints of religious themes... Therefore, some people say that these paintings should not be viewed as religious paintings, but as art."

The Vimalakirti Sutra transformation painting on the east wall of Cave 103 at Mogao Grottoes.

When discussing the artistic value of the Dunhuang murals, Dong, with the keen eye and appreciation of an artist, eloquently recounted many vivid and moving details in the murals, rather than judging them from a professional perspective such as composition, form, and color. This allowed students to genuinely understand and appreciate these paintings, thereby cultivating a love for the murals rather than simply teaching techniques. This is the style of a true educator.

For example, the "Vimalakirti Sutra Transformation" depicts the debate between the lay Buddhist Vimalakirti and Manjushri Bodhisattva. The depiction of the two is very vivid. "Vimalakirti has the demeanor of an elder, a thoughtful expression, and passionate arguments, which contrasts sharply with the depiction of Manjushri Bodhisattva." He also mentioned the Tang Dynasty, noting that "artists increasingly showed a strong interest in observing nature and a realistic approach to depicting natural objects... Tang Dynasty bodhisattvas had more human qualities and were closer to the humanism of the Renaissance, which is quite positive. For example, Ananda is depicted as a young philosopher, and Kasyapa as an elderly philosopher, which is more folk-like and realistic than earlier murals."

Vimalakirti in the Vimalakirti Sutra mural on the east wall of Mogao Cave 103

Manjushri Bodhisattva in the Vimalakirti Sutra mural on the east wall of Mogao Cave 103

For example, in "Nirvana Transformation," "the soul of Shakyamuni leaving the body is not inherently tragic, but the reactions that follow are quite different: the great Bodhisattvas understand the meaning of death and are indifferent to it. The younger disciples, whose Buddhist enlightenment is lower, are different. The Arhats are better, while the younger disciples mourn very passionately, and the princes and their subordinates from various countries are even more grief-stricken. In the portrayal of these different characters, the realistic creative method is fully demonstrated."

The Nirvana Sutra transformation painting on the west wall of Mogao Grottoes Cave 148

For example, in the "Lotus Sutra Transformation", the patient waits for the doctor in an emergency. "The contrast between the poor doctor and the noblewoman is a realistic expression, and at the same time, it is wonderful to connect the two verses and unify them in one picture."

Dong specifically mentioned that "Dunhuang art and Western painting share similar humanistic characteristics. For example, Bodhisattvas and Buddhist disciples are gods, but painters often endow them with humanity, depicting gods as 'humans'."

The last topic in Dong's lecture was the nationalization of Buddhist art. Dong believed that Buddhist painting underwent a process of nationalization in both India and China. In India, Buddhism was born in the 6th century BCE. During the reign of Ashoka (3rd century BCE), Buddhism flourished and spread throughout India. In the Gandhara region of the northwest, Greek and Buddhist cultures merged to form Gandhara art, which featured figures with Greek facial features, wavy hair, and Greek-style drapery folds. During the golden age of classical Indian culture, the Kita dynasty (4th-7th centuries CE), sculptures also developed Indian characteristics, such as thinner clothing, resembling the Cao Yi Chu Shui style of Chinese painting.

Mogao Grottoes Cave 217, Lotus Sutra Transformation Painting

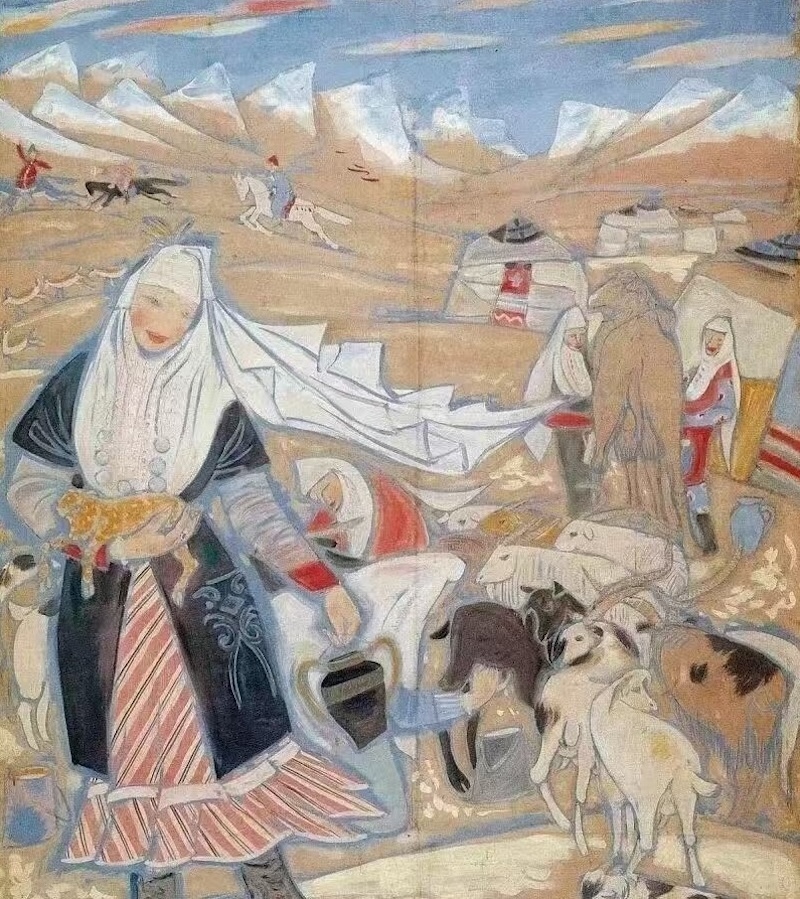

Dong said that Chinese Buddhist art also underwent such changes. Early works, such as those from the Thousand Buddha Caves and Yungang Grottoes in Datong, were influenced by Gandhara style, exhibiting an exoticism unlike that of Chinese Buddhas. However, a nationalization shift quickly followed. From the hair, faces, and clothing of figures to the treatment of mountains and rivers, composition, and architecture, everything became increasingly Sinicized. For example, the kasaya (monk's robe) transformed into long, flowing Han-style robes; the elaborate lotus pedestals were Chinese; the architecture adopted the style of Han dynasty gate towers; and the composition incorporated the continuous structure and inscriptions of the Wu Liang Shrine. "More importantly," Dong said, "the content became distinctly Han Chinese, as were the lifestyles—clothing, boats, and vehicles—immediately conveying a sense of localism rather than exoticism. This made Buddhism seem like it originated in China, a Chinese affair, so that the common people could appreciate it and accept it without feeling alienated." Even elements unrelated to Buddhism were added, such as the images of the Queen Mother of the West, Fuxi, and Nuwa. In terms of artistic techniques, the use of color, color treatment, and line work all showed Han dynasty influence. By the Tang dynasty, this nationalization had reached its mature stage.

As an artist, the evolution of Dunhuang Buddhist art allowed him to see the path of artistic development from the introduction of Western culture to its Sinicization. This was a major gain from his study trip to Dunhuang. Nationalization became a concept that Dong pursued afterward, proposing the so-called "Chinese style of oil painting": "In terms of painting style, this should be the highest goal that we oil painters strive for." His masterpiece "The Founding Ceremony of the People's Republic of China" is a product of this concept. If he had gone to France to study at that time, perhaps his subsequent development path would have been completely different. The trip to Dunhuang also made Dong particularly fond of murals. He said, "Ancient Chinese and Western murals can be said to have met... We must have this kind of magnanimity, absorbing foreign things and also making them our own." Afterward, he made great efforts in mural creation and talent cultivation, and was hailed as an enlightenment master of the modern Chinese mural movement.

Dong Xiwen's oil paintings

Dong Xiwen's "The Founding Ceremony of the People's Republic of China"

The historical changes in the Dunhuang region allowed him to view the development of things from a broader perspective and from the perspective of the grand history. Subsequently, Dong's creative themes focused on depicting major historical events. In the 1950s, Jiang Feng once commented that Dong was "a painter with great ambitions who enthusiastically pursued exciting major events as creative themes." This was not unrelated to his experience in studying Dunhuang art. Although some people ridiculed him as a "painter for the court," his desire to reflect the great changes in history was indeed his wish.

postscript

This year, the Beijing Exhibition Center is hosting the "Such is Mogao – Dunhuang Art Exhibition," which uses 3D technology to recreate several caves in Dunhuang. It's a highlight among Beijing's many exhibitions, and it's a pleasure to experience the charm of Buddhist caves again in Beijing. The renewed interest in the Silk Road and Dunhuang reminds me of my second uncle, Dong Xiwen (my mother's cousin), and his experience visiting Dunhuang 80 years ago, and the impact it had on his life. It's something worth reflecting on today, which is why I wrote the above.

September 2025, at Chaowai Apartment, Beijing

(This article was originally titled "Dong Xiwen and Dunhuang," and has been abridged.)