On November 7, the day of Lidong (the beginning of winter), the wind carried the lingering fragrance of osmanthus blossoms from the Huangpu River, permeating the exhibition halls and surroundings of the Shanghai Museum of Contemporary Art (PSA). The 15th Shanghai Biennale, "Have the Flowers Heard the Bees?", officially opened there that afternoon.

Japanese artist Aya Yamazaki began her opening performance in the soaring space of the Shanghai Museum of Contemporary Art, uttering her first wordless chant amidst the yellow flowers of "Forest Illusion." The sound echoed through the building. She closed her eyes, listened to the direction of the echo, and responded with a new pitch.

The Paper learned that the 15th Shanghai Biennale presents over 250 works by 67 artists/groups from around the world, including 16 Chinese artists/groups, and more than 30 newly commissioned and newly produced works. The exhibition is curated by chief curator Kitty Scott, co-curators Daisy Desrosiers and Tan Xue, marking the first time in the history of the Shanghai Biennale that a female-led curatorial team has led the event.

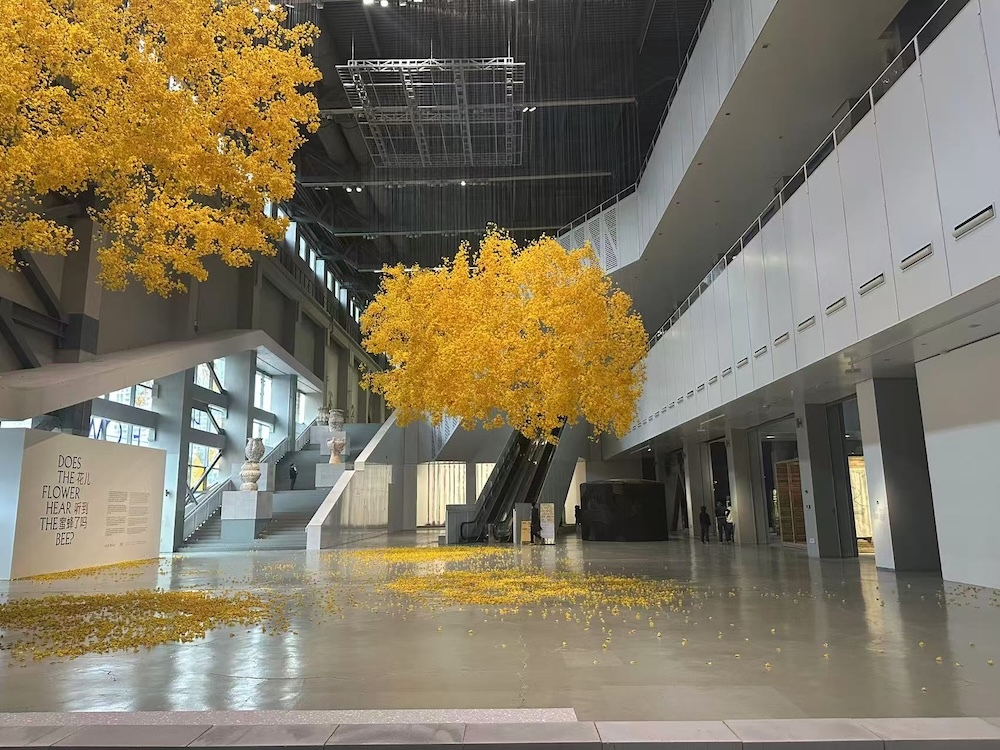

At the exhibition, Allora & Calzadilla's work "Forest Illusion" is on display.

"Can flowers hear bees?"—This almost poetic scientific question stems from research at Tel Aviv University in Israel: flowers can "hear" the frequency of bees' wingbeats, thus secreting sweeter nectar within minutes. This cross-species response mechanism became a metaphor for the curatorial team—art is precisely a way for humanity to "hear" each other with the world. At the exhibition's press conference, the curatorial team repeatedly emphasized the importance of engaging all five senses.

More than 40 Chinese and foreign artists attended the opening ceremony, marking the largest gathering of participating artists since the Shanghai Biennale moved to the Shanghai Museum of Contemporary Art.

At the exhibition, Liang Huigui's works

“I think the biggest challenge facing this year’s theme is how to break away from existing concepts and research and create a new life and creative structure,” said Gong Yan, director of the Shanghai Museum of Contemporary Art, at the opening ceremony of the exhibition. “But in the garden, it may be difficult for us to distinguish the boundaries between nature and culture, ecology and politics and economics, because it is another world full of emergence, meandering, overlap, reincarnation, chance, compromise, and symbiosis and co-construction.”

Like a traditional Chinese literati garden or a Japanese strolling garden, the exhibition unfolds gradually and imperceptibly. From the whispers of plants to the hum of the city, from inhuman intelligence to the energy flow of human society, it is a journey that transcends perspectives and fosters diverse perceptions. Viewers can explore and wander freely, with artworks scattered like seeds throughout the Shanghai Museum of Contemporary Art. Each turn, each glance, reveals a new composition, showcasing the continuous evolution of artworks, architecture, and their interrelationships.

At the exhibition, Francis Ellis's work "Children's Games" is on display.

Beneath the floral shadows, the Caribbean breeze meets the Shanghai light and shadow.

In the spacious lobby of the Shanghai Museum of Contemporary Art, thousands of artificial flowers suspended in the air create a weightless forest, instantly immersing viewers in the theme of "flowers." This work, titled *Forest Illusion* (2025), is by Allora & Calzadilla. They create flowers from recycled plastic and shape them into trees, but without trunks, leaves, or branches, prompting viewers to contemplate the source of their loss.

Exhibition site

The artwork features the Yellow Trumpet Tree, an oak species native to the Caribbean. Since the colonial era, the local ecosystem has suffered long-term exploitation, and these "floating flowers" originate from that deforested and displaced land. The slight swaying of the flowers is not caused by airflow within the museum, but rather by real-time data from the Caribbean trade winds—the same trade winds that once propelled colonial fleets across the Atlantic, now traversing thousands of miles through data networks to reach this space that was once a power plant.

The "Forest Illusion," a forest in the Caribbean that disappeared due to over-logging or never truly grew, is vividly displayed in this building, creating a sense of alienation.

Japanese artist Aya Yamazaki presented the opening performance under the theme "Forest Illusion".

Beside it, “Floating Shadows” (2020), created by the same group of artists using light, sound, and memory, casts a shadow onto the wall and the ground. This beam of light imitates the scene in the Absalon Valley of Martinique—sunlight shines on the forest, passing through the canopy and casting dappled light and shadow through the gaps in the trees.

In 1941, Aimee César and Susanna César, along with other exiled Surrealists, traversed this forest, fleeing Europe. Their brief encounter intertwined anti-colonial sentiments with poetic visions. Although a light drizzle fell when the exhibition opened, the projected image of "Floating Shadows" appeared intermittently. One can imagine that on a sunny day, the light in the exhibition hall would change in real time as the sun moved across Shanghai, merging two different geographical regions into the same space of light and shadow.

Standing beneath the flower shadows, amidst that play of light and shadow, one seems to feel a distant, historical, and indescribable tremor.

At the exhibition, the hazy "Floating Shadows" is a work that is easy to miss.

The inscription "THE FORM OF THE FLOWER IS UNKNOWN TO THE SEED," written beneath the shadows of flowers, is a work by Thai artist Rirkrit Tiravanija. It is inscribed on a concrete wall, resembling a verse.

Rikri Tiravani's work, "The Form of the Flower Is Unknown to the Seed."

Tiravani is known for his "social performance art"—he cooks, builds tents, organizes exchanges, and creates concise and powerful text. For him, these sentences are like road signs on a desert road; people pass by in a hurry, and whether they are touched depends entirely on whether the text enters their consciousness, just as people wear T-shirts with words printed on them without knowing what they mean.

However, in the art museum, the meaning of the words is not just a fleeting glance, but also an expression of philosophy and concepts. It is reported that a screen printing station will be set up at the exhibition site in the future, where visitors can have his signature phrases printed on their clothes with the help of staff.

Exhibition site

Beyond images, sound is almost everywhere.

Beyond images, sound was almost everywhere in this year's Shanghai Double 11. Sometimes it was children's singing, sometimes the rhythm of the wind, and sometimes the silence suppressed by language. It lurked in the air, in the walls, and in the breath. Artists were both speakers and listeners, and artistic creation shifted from expression to resonance.

Exhibition site

Icelandic artist Ragnar Kjartansson's video work, *A Boy, a Girl, a Bush, a Bird*, places sound on the boundary between ruin and romance. He and a friend play in a decaying banana plantation, a "pocket symphony" of longing echoing between corrugated iron and pipes. The sound of wind, the resonance of metal, and human chanting intertwine to create an unstable melody. It sounds like an elegy about time. Here, sound is not music, but a testament to existence.

At the exhibition, Ragnar Kjartansson's video work, "A Boy, A Girl, A Bush, A Bird," is featured.

In contrast, Francis Alÿs's *Children's Games* appears softer and more expansive. The screens are arranged in a circular soundscape, depicting children running and singing in the streets of Kabul, Havana, or Lima. The rhythms of the games, the whistles, and the sounds of blowing seashells create harmony—a non-institutionalized order, a natural cooperation. This seems to remind us that children's games also involve mutual enrichment that transcends cultural differences.

At the exhibition, Francis Ellis's work "Children's Games" is on display.

In Christine Sun Kim's mural "Heavy Relevance," sound is completely "extracted." A musical staff dragged down by quarter notes stretches across an entire wall of the Shanghai Museum of Contemporary Art, seemingly silent, yet visually creating a vibration. She uses the rhythm of sign language to "rewrite" the structure of hearing, and when viewers face this wall, they often subconsciously hold their breath—that is another way of listening.

At the exhibition, Christine Sun Kim's "Heavy Relevance" is displayed in the back, while Aki Inoguchi's "How to Sculpt a Sculpture" is displayed in the front.

Alvaro Barrington's sound installation, *Returning Home/I Said I Am, I Said*, returns "listening" to the realm of the body, the land, and belonging. On the first floor of the exhibition hall, he constructed a "hut" using corrugated metal panels, recycled wood, and fabric. As visitors enter, the air is filled with the deep, resonant sounds of old-fashioned cassette tapes. Inside the hut, paintings depict plants and coastlines, while an old cassette radio plays the lyrics of "I Said I Am, I Said," a question of "where do I come from" amidst movement and migration, and also imbued with a sense of belonging.

At the exhibition, Álvaro Barrington's cottage, titled "Returning Home / I Say...I Am," is on display.

Born in Grenada, the southernmost island of the Windward Islands in the Eastern Caribbean, Barrington says, "I returned to the place where I spent my childhood and realized that music, architecture, and language had long been part of my being." His works invite viewers to sit in sculpted stone chairs and listen to how floating sounds enter their memories. At that moment, listening is no longer a passive act, but an active and interactive practice.

In the theme "Did the flowers hear the bees?", the sound enters the ear unexpectedly, sometimes rising and falling, sometimes whispering, sometimes silent, and needs to be slowly discovered through the viewer's personal experience.

Exhibition site

Humanity and Nature from an Asian Perspective

Within the exhibition space, what we "listen to" is not only the voices the artists have pre-set, but also the various forms of life. We listen to a world of symbiosis. In this process, the works of Asian artists offer another way of understanding "listening"—not just through the ears, but through the language of time, matter, and plants, telling the story of how humanity, after experiencing the acceleration and rupture of modernity, can become part of nature again.

Chinese artist Hu Xiaoyuan's "I Have Roots, But I'm Drifting" is quietly suspended in a seemingly silent space and time. Seemingly fragile materials such as conch shells, insect wings, wool, and raw silk are woven into her poems and manuscripts, as if listening to the breath left by time.

At the exhibition, Hu Xiaoyuan's works

In the same gallery, Japanese artist Aki Inomata uses humor and experimentation to allow "nature" to regain creative control. In her work "How to Sculpt a Sculpture," she invites beavers to participate in the creation—wooden blocks are placed in a zoo's pool, where beavers gnaw out "sculptural" shapes. She then enlarges these pieces of wood, bearing the teeth marks, three times their original size, transforming them into abstract sculptures brimming with primal power in the gallery.

The boundaries between artists, animals, and materials are blurred: who is creating? Is it the beaver's instinct, the texture of the wood, or the human intention? With this cross-species collaboration, Aki Inoguchi raises a gentle yet profound question—art is a symbiotic language.

At the exhibition, Aki Inoguchi documented the creative process of "How to Sculpt a Sculpture".

This reflection on "symbiosis" also extends to Huang Yongping's *The Peach Blossom Spring* ( 421–2008 ). As early as the 1990s, Huang Yongping pointed out that East and West, "I" and "other," are not fixed concepts. The work juxtaposes Tao Yuanming's *The Peach Blossom Spring* with the ideas of Lao Tzu, Fukuyama, and Kojève, revealing the illusion and cycle of utopia. It makes "Peach Blossom Spring" a fluid space of thought—neither a return to nature nor an escape from reality, but rather a contemplation of the philosophical question of "coexistence."

At the exhibition, Huang Yongping's manuscript of "The Peach Blossom Spring ( 421–2008 )" is on display.

Like a "Shangri-La," the exhibition uses the industrial language of the power plant building itself, employing exposed concrete bricks to create artificial terrain that runs throughout the space, allowing visitors to wander and experience ever-changing scenery. It presents a constant invitation and a sense of discovery. According to the exhibition design team, all(zone) studio/Ratchapong Chochuy, viewers will find their own rhythm within the exhibition, and contemplation can occur between stillness and movement.

Opening performance by Yamazaki Aya.

The opening performance was presented by Japanese artist Aya Yamazaki. Standing in the soaring space of the Shanghai Museum of Contemporary Art, Yamazaki believes that "every place is inherently singing." The materials, structure, and volume of architecture all possess their own acoustic topology. She uses her ears, skin, and vocal cords to probe the echoes of these spaces, allowing sound to become a channel connecting people and places. At 3 PM on November 8th, Yamazaki will also present a special performance at the Bonsai Garden of the Shanghai Botanical Garden.

In addition to the Shanghai Museum of Contemporary Art as the main venue, the 15th Shanghai Biennale's "Urban Project" will meet the public at various locations, including the Jiayuanhai Art Museum in Malu, Jiading District, the Shanghai Botanical Garden, tbh's Hut on Taojiang Road, and klee klee at the Shanghai New World Art Center. Simultaneously, the main exhibition catalogue and a reader will be released concurrently with the exhibition. The main catalogue, centered on the artists' own narratives, also includes essays from the three curators and extensive documentation of the exhibited works, offering another way to explore the question, "Can flowers hear bees?"

Exhibition Publications

This year marks the 29th anniversary of the Shanghai Biennale. Looking back on its growth, the Biennale's uniqueness lies in its consistent response to the upheavals and opportunities of its time. "The Biennale is changing Shanghai citizens' understanding of art. At the same time, contemporary art has become a cultural lifestyle for citizens to participate in society and build communities. This Biennale hopes to establish a harmonious relationship between audiences, artists, and museums, allowing art institutions to shoulder the mission of our time, and enabling artists' unique, prescient magic to bring reflection and hope to the world," said Gong Yan.

Exhibition press conference site

The exhibition will run until March 31, 2026.