Camille Pissarro (1830-1903) is hailed as the spiritual father of Impressionism and a central figure in its "patriarchal" style, but for him, the identity of "father" was even more significant. He rejected the preference of his contemporaries for upper-class themes and preferred to depict ordinary scenes of daily life.

The Paper has learned that the exhibition "Honest Gaze: Impressionism by Camille Pissarro" is currently on display at the Denver Art Museum in the United States, comprehensively reviewing the artist's career with over 100 paintings from nearly 50 international museums and private collections. His selected letters also offer insights into how he, as a father, educated his eight children. (See the end of the article for the letters.)

Pissarro, "White Frost of Enneri", 1873.

A critique of the Parisian art scene and the individual's artistic journey

Pissarro was born on the Caribbean island of St. Thomas and later settled in France, playing a highly influential role in the 19th-century Parisian art world. Matisse once asked Pissarro what an Impressionist painter was. "An Impressionist painter is an artist who paints different works each time," Pissarro believed. "Painting should not be literary or historical, nor political or social, but merely an expression of emotion."

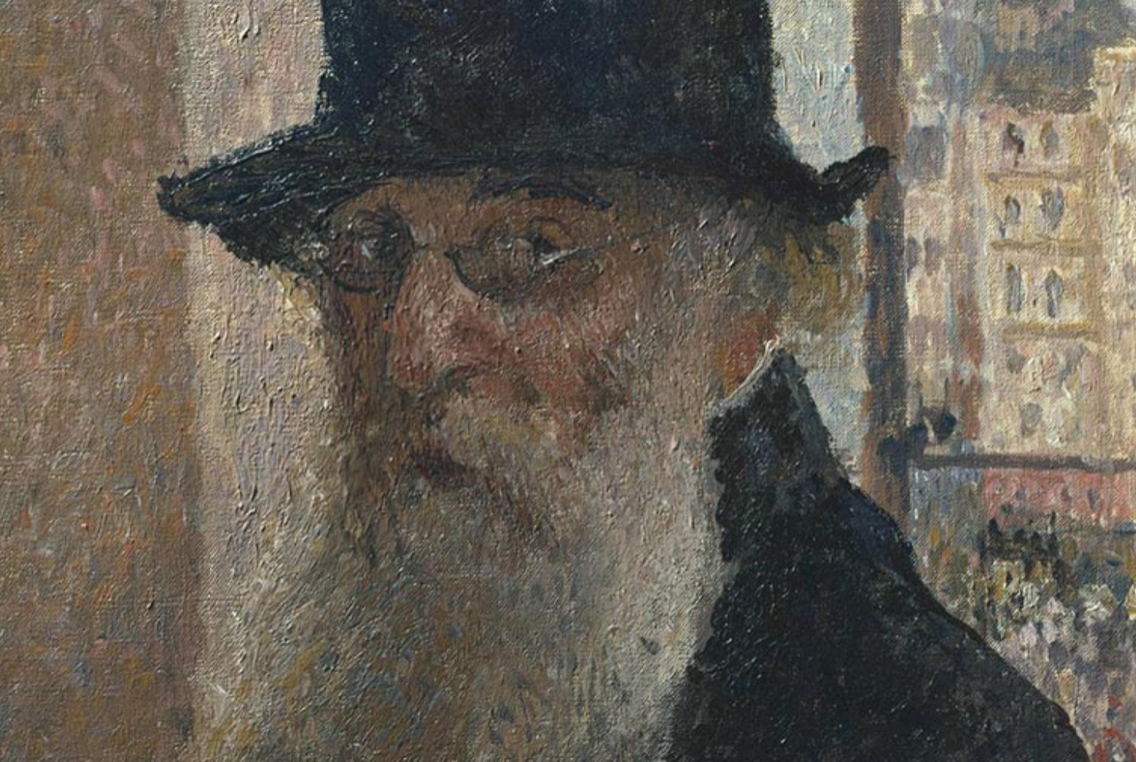

Pissarro's Self-Portrait, 1903

At the age of twelve, Pissarro was sent by his father to study at the Académie Savory in Passy, near Paris, where he first developed an appreciation for the French masters. After returning to St. Thomas at seventeen, he worked as a port clerk in his father's company until he was twenty-one, when he met the visiting painter Fritz Melby and accompanied him to Venezuela in 1852. During his time in Caracas, Pissarro created numerous landscapes, rural scenes, and drawings.

After returning to Paris, Pissarro served as an assistant to the Danish painter Anton Melby and studied under several masters. However, he gradually found the traditional teaching methods "suffocating" and eventually chose to study under Corot, devoting a great deal of time to sketching and painting the French countryside.

Pissarro, *Young Peasant Girl with a Straw Hat*, 1881.

Pissarro, "Frost, Peasant Woman Lights Fire", 1888.

Pissarro was deeply disappointed with the annual exhibitions of the Paris Salon, which were then hailed as the pinnacle of Western art. He keenly perceived the injustice and elitist tendencies of this exhibition system and successfully persuaded other artists to reflect on its limitations. During the Franco-Prussian War of 1870-1871, Pissarro moved with his family to the suburbs of London. During his time in England, he met and became acquainted with Monet, and the two of them drew significant inspiration from the works of British painters such as Constable and Turner.

After the war, Pissarro returned to France only to face a devastating blow: of the nearly 1,500 works he had created over twenty years, only 40 survived; the rest were destroyed by soldiers, some even used as floor mats outdoors. In 1874, Pissarro, as a key founder, participated in the establishment of the "Association of Anonymous Painters, Sculptors and Printmakers" and curated the landmark exhibition later known as the first "Impressionist Exhibition." Participating artists included Monet, Renoir, Sisley, Cézanne, Degas, and Morisot. Pissarro believed that "painting should be neither literary nor historical, nor political or social, but merely an expression of emotion." Several of the works exhibited in the 1874 exhibition were loosely brushed landscapes, capturing the light and impressions of specific moments.

Pissarro, View from the Window, Erlani, 1886.

Pissarro, "Pear Tree in Full Bloom", 1894.

Pissarro, Rue Saint-Honoré, Morning, Sunlight Effect, 1898

"Le Pont-Neuf, aprèsmidi, soleil" (The Pont Neuf, in the Afternoon), 1901

As a group, the Impressionist artists sought to document the modern world around them by capturing the ever-changing interplay of light and color. They emphasized texture, tone, and vibrant colors, rather than traditional compositional methods. The first Impressionist exhibition initially received a lukewarm reception, deeply affecting Pissarro. Moreover, he was also experiencing personal grief at the time: his nine-year-old daughter, Jeanne, had passed away a week before the exhibition's opening.

As subsequent exhibitions met with lukewarm reception, by the fourth exhibition in 1879, Renoir, Sisley, and Cézanne had all withdrawn, and Monet left the following year. Pissarro was the only artist whose work was selected for all eight Paris Impressionist exhibitions. In 1884, Pissarro moved to the town of Errand, where he met avant-garde artists Seurat and Signac, and briefly embraced Neo-Impressionism, which emphasized the contrast of color dots. However, he soon returned to his own artistic path and continued to explore.

Pissarro died of septicemia on November 13, 1903. This artist, who only gained critical recognition in the final stages of his life, is now widely regarded as a key figure in the Impressionist movement, and his artistic legacy has become an indispensable chapter in the history of modern art.

Around 1886, the Pissarro family in a field in Elrani.

Pissarro as a father

“When you feel the urge to create, do it no matter the cost… You will surely reap the rewards. It is very rare to have such a desire (for art), so we have a responsibility to put it into action, and to act immediately, because procrastination will only cause the desire to dissipate. Go for it, do it!” Pissarro once encouraged his children in this way.

Camille Pissarro was later hailed as the spiritual father of Impressionism and a central figure in its "patriarchal" style, but for him, the identity of "father" held even greater significance. Lauren Thompson, an expert in the Learning and Engagement Department at the Denver Art Museum, shared some of the letters from this exhibition, which are worth reading carefully.

Pissarro's parents moved to Paris around 1860, and it was there that he met Julie Villet, his mother's kitchen maid, and fell in love. When Pissarro told his parents they intended to marry, they faced opposition—Julie was not only from a working-class background but also a Catholic. In fact, Pissarro's mother never fully accepted the marriage or Julie as a person. Nevertheless, the couple lived together and had eight children (only six survived to adulthood—all of whom became artists). Despite the lack of acceptance and numerous hardships—financial difficulties, anti-Semitism, the death of family members, and during the Franco-Prussian War, when soldiers occupied Pissarro's home and destroyed many of his paintings—their marriage ultimately lasted.

He deeply loved his children and valued their education, and the letters that have survived allow us to glimpse the close father-son relationship between them.

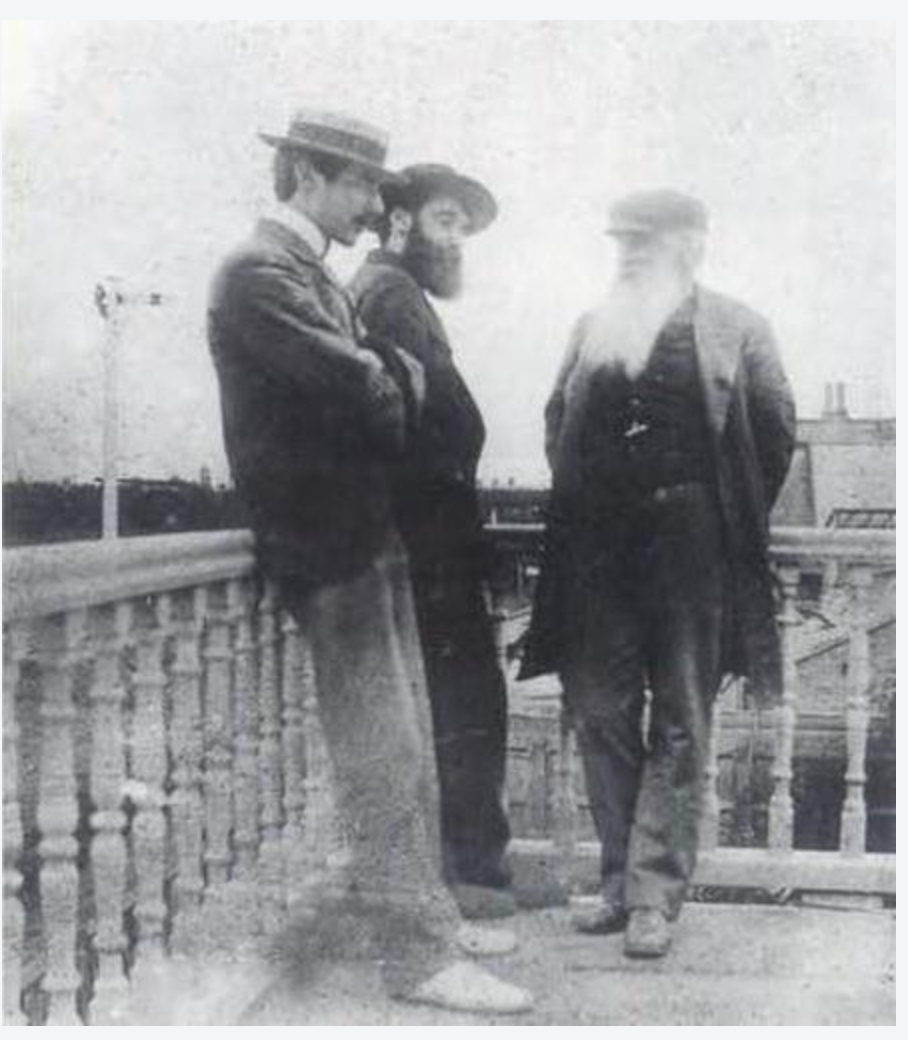

Pissarro with his sons Lucien and Felix, photographed in 1897. Both of his sons eventually followed in the footsteps of artists.

Pissarro's letters to his eldest son, Lucien, vividly reveal the artist's inner world—his anxieties, complaints, hopes, and suggestions. Although these letters were not originally intended for publication, they offer glimpses into his private and often unexpected life. For years, Pissarro joyfully observed and documented his children's artistic growth, describing it with pride.

In 1889, while his 18-year-old son George was studying decorative wood carving at an arts and crafts school in London, Pissarro wrote to him about his younger siblings: "Titi (then 15) works with me in the studio every day, and her studies are going very well; her hands are steady... but she hasn't grasped the value yet, but she will later; Titi is lazy and still likes to play and run around, which is normal for her age... Rudolph (11) is still the same as always, grumpy and thoughtful; he's busy fiddling with his little dolls and does nothing else; he hasn't started studying seriously yet... Paul-Emile (5) is making spider legs, which in his imagination become cars, horses, drivers, hens, birds, and so on. Kokote (8) is sewing and taking care of her dolls."

A month later, Pissarro saw progress and wrote to George again: "Titi has been drawing, although he is still a bit lazy, but he loves sports - that's okay, he is improving little by little."

However, prolonged financial hardship led to disagreements between Pissarro and Julie regarding their children's education. They were particularly worried about Lucien's future: Julie wanted him to find a job to help support the family, while Pissarro encouraged him to focus on art. In a letter to Lucien in 1884, Pissarro wrote: "Your mother is very worried... She says I let you pursue art, but didn't teach you to think about making a living; I don't know if I made a mistake."

Portrait of Jeanne Pissarro, 1872.

Pissarro's letters to his children are filled with a father's advice and encouragement. In 1891, he wrote to Lucien, who had already achieved some success: "Now, based on my own experience, my advice is: when you feel the urge to create, do it no matter the cost... You will surely reap rewards. It is very rare to have such a desire (for art), therefore we have a responsibility to put it into action, and to act immediately, because procrastination will only cause the desire to dissipate. Go forward, do it! Remember, act!"

Pissarro continued to encourage children to find their own artistic expression. On June 7, 1893, he wrote to Lucien again: “I hope that when you return to London, you will devote yourself to your studies and freely express your emotions. I look forward to your future very much—your existing knowledge is enough to give you confidence. Your excellent sculptures are proof of this; now you just need to find a way of expression that resonates with your spirit. Don’t be discouraged; trust your intuition.”

Although the house in Éranny was always filled with the noise and running of children, as they grew older, Pissarro began to lament the approaching empty nest. In a letter to Lucien dated October 20, 1895, he wrote: “I long to go to Paris and see what is happening there. Despite the heavy workload, I feel extremely bored in Éranny… Is it because of worries about money? Or weariness with the coming winter? Or boredom with old subjects? Or a lack of material when I paint figures in my studio? All these reasons are part of it, but what saddens me most is watching this family slowly fall apart. Coccote is gone, and Rodot will soon be leaving too! Can you imagine the two of us old people, all alone in this big house all winter?”

In the last year of his life, Pissarro rented a large enough apartment in Paris for his wife Julie and children to live with him. Soon after, he fell ill. At the age of 73, he passed away peacefully surrounded by his children.

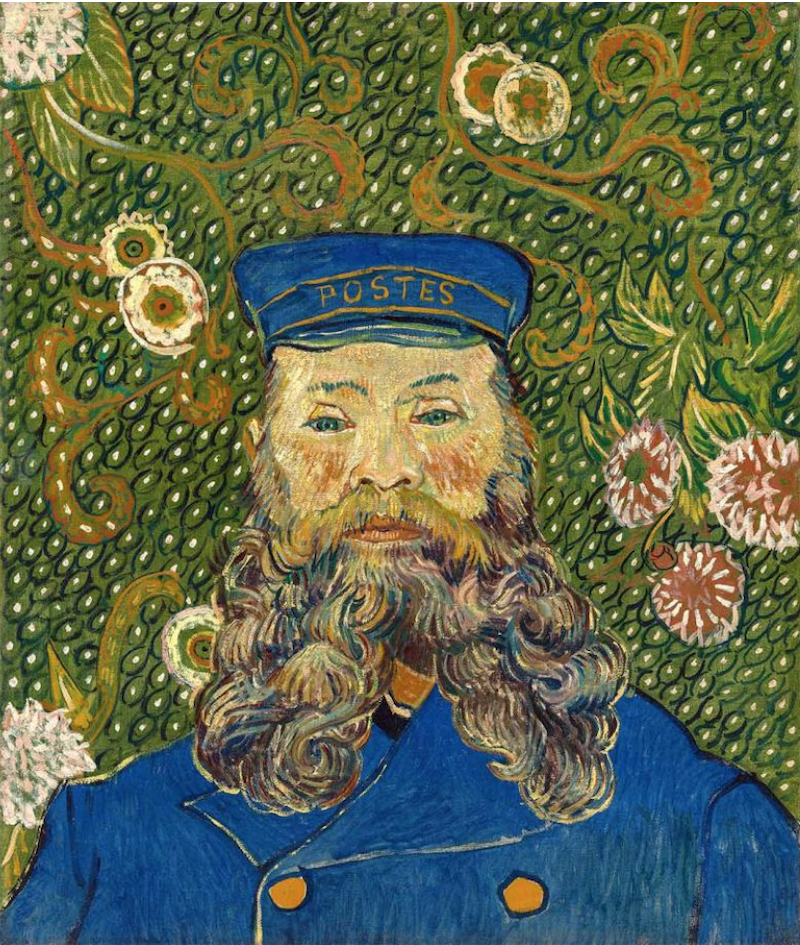

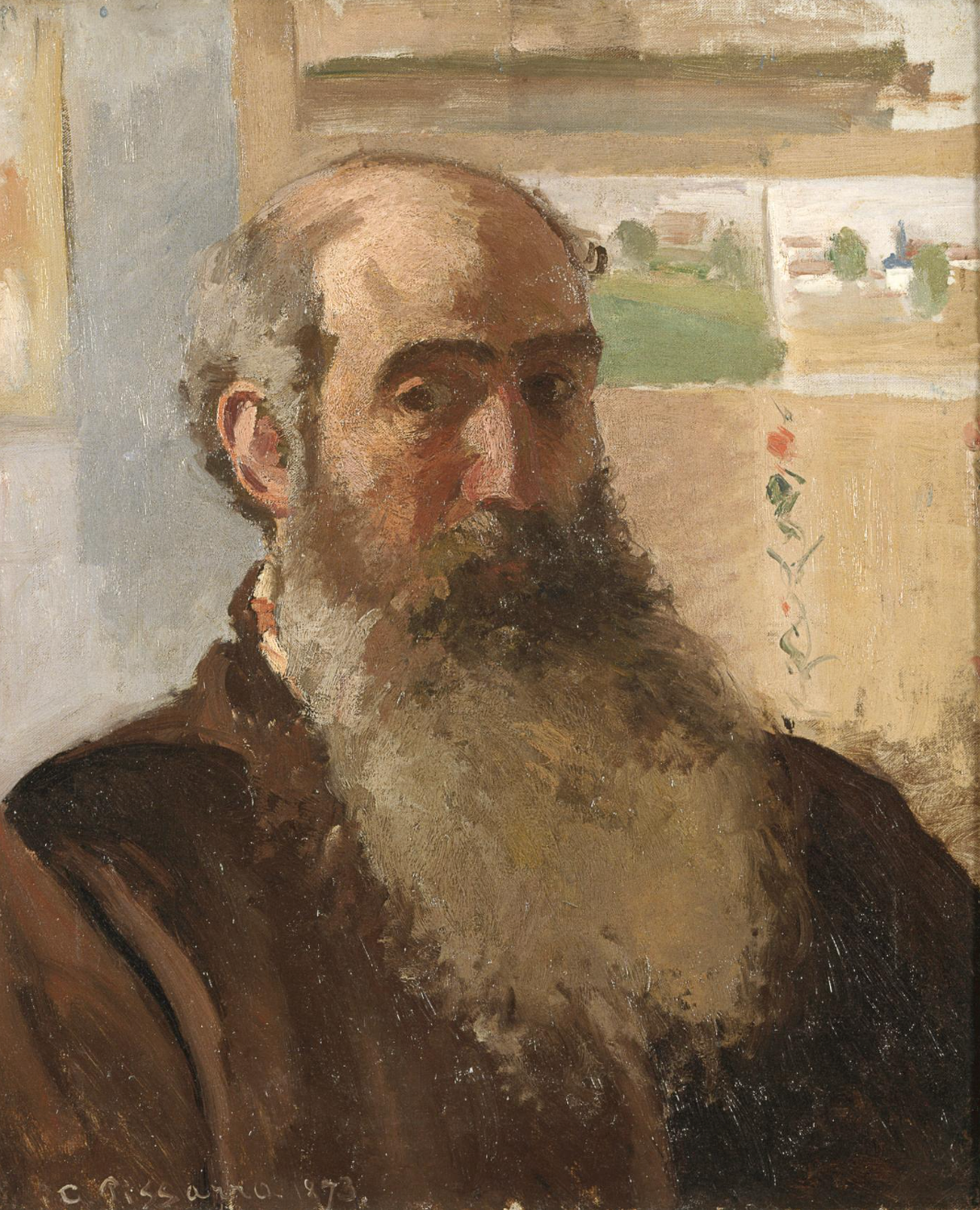

Self-portrait, 1873.

This exhibition, jointly organized by the Denver Art Museum and the Barberini Museum Potsdam, Germany, will run from October 26, 2025 to February 8, 2026.

Image and reference source: Denver Art Museum, USA