This year marks the 110th anniversary of the birth of Feng Jizhong (1915-2009), a renowned architect, architect, and architectural educator, and an important founder of modern architecture in China. The College of Architecture and Urban Planning of Tongji University recently held a series of commemorative activities and specially established the "Feng Jizhong Research Room".

In the narrative of modern Chinese architectural history, Feng Jizhong's name is often associated with "He Lou Xuan," but compared with his childhood classmate I.M. Pei, Feng Jizhong seems to have rarely been in the spotlight. His name is scattered on campuses, in exhibition halls, and among the pages of books: he was a key figure in promoting the establishment of the architectural education system in New China, and is known as the "master among masters" by countless architects. His thoughts and works have profoundly influenced more than one generation of Chinese architects.

Feng Jizhong's only daughter, Feng Ye, recently donated a batch of Mr. Feng Jizhong's academic archives to the College of Architecture and Urban Planning of Tongji University, and gave an exclusive interview to The Paper | Art Review, recounting her memories of her gentle father and her godfather—the art master Lin Fengmian.

Feng Jizhong’s only daughter Feng Ye

In Feng Ye's memory, her father, Feng Jizhong, always possessed two qualities: one was the rigor of an architect, and the other was the gentleness of a father.

But what she talked about most was the latter.

Feng Jizhong and his wife with Feng Ye as a child

"In my heart, he is the best father in the world." This sentence seems to sum it all up. Feng Ye is Feng Jizhong's only daughter and the only child from his only marriage. "He married late, so he cherished me especially. I've always felt that he reserved all his patience for his family."

That "lateness" is related to his family story.

Feng Jizhong's time studying in Europe

On the Feng Family: Cross-cultural Integration in Traditional Family Values

Feng Jizhong came from a prominent family. His grandfather, Feng Rukui, was a Hanlin scholar and the last governor of Jiangxi during the Qing Dynasty. His mother came from the Zhu family of Baoying, a family that produced three Jinshi (successful candidates in the highest imperial examinations). This family background brought with it a traditional set of customs and traditions, but also a heavy fate for the eldest son. When Feng Jizhong was in high school, his father passed away, and his mother became a widow early on, placing all her hopes on her eldest son.

The "Feng Jizhong Study Room" at the College of Architecture and Urban Planning, Tongji University, displays early photographs of Feng Jizhong (1915-1935).

In 1936, Feng Jizhong went to the Technical University of Vienna in Austria to study architecture. Before his departure, his mother told him, "I don't like foreign women." This advice, passed down from the old era, was something Feng Jizhong kept in mind.

The "Feng Jizhong Study Room" at the College of Architecture and Urban Planning, Tongji University, displays photos of Feng Jizhong during his study abroad period (1936-1946).

Upon completing his studies, he was caught in the outbreak of World War II, unable to return home. He remained in Austria and Germany to continue his studies and work, eventually obtaining qualifications as an engineer and a senior architect. It was an era ideal for a young architect to establish himself in Europe, but he never started a family—his mother's words were more important to him than any personal choice.

A rendering assignment by Feng Jizhong during his studies at the Technical University of Vienna. Source: History Museum of the College of Architecture and Urban Planning, Tongji University.

In 1946, he finally returned to China. He quickly threw himself into construction work: serving as an adjunct professor at Tongji University and Jiaotong University in Shanghai, while also working as an architect for the Nanjing Urban Planning Committee. That year, he juggled these three positions. His personal life was once again put on hold.

In 1946, Feng Jizhong returned to China on a ship. (Source: History Museum of the College of Architecture and Urban Planning, Tongji University)

Feng Jizhong finally got married in 1951, when he was thirty-six or thirty-seven years old. His wife was Xi Suhua, who came from the Xi Family Garden. In 1953, they had a daughter, Feng Ye. "He was an extremely responsible person to his family," Feng Ye told The Paper. "From a young age, I felt that he was a model husband and a model father."

According to his daughter Feng Ye's account, this figure, who is considered an important figure in the history of modern Chinese architecture, did not first appear as an "architect," but rather as a father who was almost traditional, gentle, and carried the old family style. At the same time, he was also an art lover who was well-versed in music and opera.

Wedding photo of Feng Jizhong and his wife (Photo by Jin Shisheng)

Feng Ye told The Paper that when Feng Jizhong was studying in Europe, he often bought standing tickets with a Czech classmate to watch concerts and operas in Vienna. "They would go to every good concert and opera." This experience nurtured his father's artistic sensitivity and musical literacy.

As for traditional Chinese opera, Feng Jizhong is almost a semi-expert. Feng Ye recalled that her father grew up in Beijing, and there were elders in his family who loved Peking Opera. Her grandmother's younger brother, Zhu Naigen, was a well-known Peking Opera enthusiast in Shanghai's first generation. The Shanghai Library now holds three rare records of the Tan and Yu schools of Peking Opera, which were recorded by Zhu Naigen. Her father was exposed to Peking Opera from a young age and could even sing excerpts from Peking Opera at a high level. Feng Ye remembered that when she was a child, her father often hummed Peking Opera in the kitchen. "At that time, we didn't have a housekeeper at home. My mother needed to teach painting at night school, and he would hum opera while heating up food for me in the kitchen." This scene is still unforgettable for her. Even when her father was around ninety years old, he could still sing Peking Opera excerpts at a team building event, and his skills were superb.

Music and opera were not only his father's hobbies, but also profoundly influenced his architectural creations. Feng Ye sensed that her father pursued rhythm and layering in his architectural designs—in the design of Fangta Garden, one can see the rhythmic feel of Song Dynasty aesthetics, while also incorporating the rationality and lightness of Western music. She said, "Sometimes, I feel that he is 'composing' in his architecture—there is the heaviness and rationality of Bach, as well as the lightness and joy of Mozart." In her eyes, this fusion of cross-cultural and cross-art forms is precisely what makes her father remarkable.

The He Louxuan materials displayed in the "Feng Jizhong Research Room"

Talking about Fangta Garden: A Garden Like a "Pearl in My Father's Eyes"

Feng Ye first entered Fangta Park in 2007. At that time, more than 20 years had passed since Feng Jizhong built Helouxuan.

When Feng Jizhong was building Fangta Garden and conceiving Helou Pavilion, his daughter Feng Ye had already gone overseas with her adoptive father and teacher, Lin Fengmian. It was a long period during which she hadn't returned to China, and she only learned about her father's garden construction in Songjiang from fragmented accounts—including rumors that he wasn't entirely satisfied with the details. This complex feeling kept her from stepping into Fangta Garden for a long time.

He Lou Xuan is located in Fangta Park, Songjiang District, Shanghai.

It wasn't until 2007 that she accompanied her father back to the garden for the first time. "The memory of that day is still very clear. The garden was a bit deserted, and the leaves weren't very lush. But as soon as we entered through the gate, the square tower stood there, and the space suddenly opened up. I was completely stunned. That sense of openness and profound tranquility made me suddenly understand why my father was so attached to this place."

Sketch of He Lou Xuan. Source: History Museum of the College of Architecture and Urban Planning, Tongji University.

Not long after, Yan Shanchun, then vice president of the Shenzhen Academy of Painting, contacted Feng Ye through a middleman, hoping to curate an architectural exhibition for Feng Jizhong. This request was somewhat unexpected for her. But it was this chance encounter that led her and her father's students to jointly prepare the "Feng Jizhong and Fangta Park" exhibition, leaving behind precious images and materials of the architect who was over ninety years old.

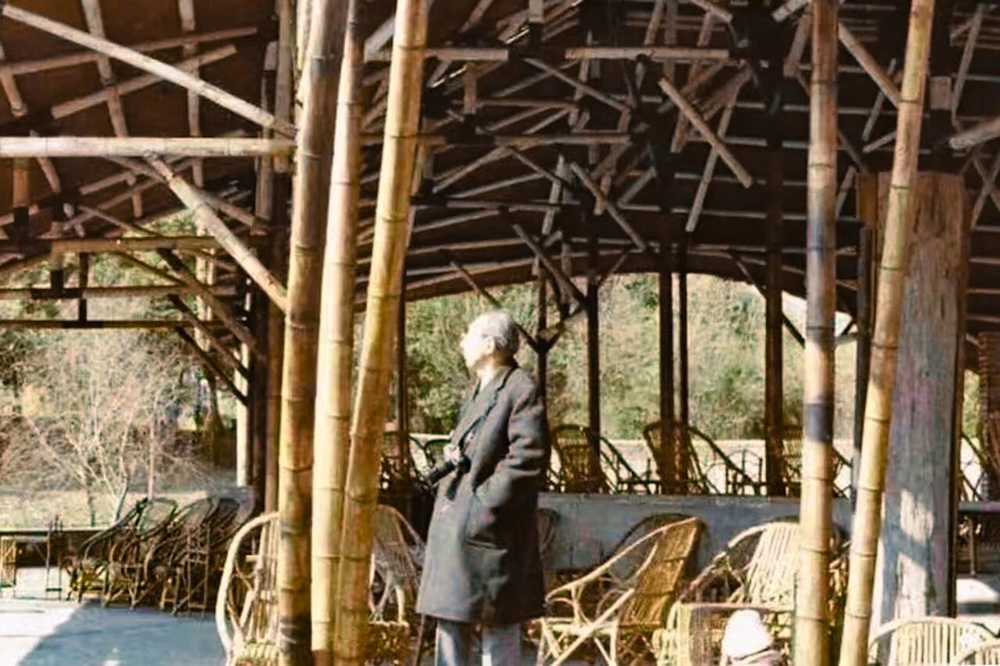

Feng Jizhong spent his later years at He Louxuan

What truly forged a deeper connection between Feng Ye and Fangta Park was a rare heavy snowfall in 2007.

That year, Shanghai was hit by a blizzard, forcing Songjiang Fangta Park to close. Feng Ye chartered a car to get there, and the park staff made an exception and allowed her in. The park was deserted; the snow-covered bamboo bent low, making soft creaking sounds. She carried her photography equipment, documenting the scene, venturing into the bamboo grove to find the perfect angle, and even "climbing" to a spot opposite Helou Pavilion to take photos, her hands and feet numb with cold. On Wangxian Bridge, she slipped and fell, tripod and camera crashing onto the stones. Fortunately, she was unharmed, and her equipment didn't fall into the water. That experience of facing the snow scene alone allowed her to feel the park's pulse and life force so directly for the first time.

Snow scene at Helouxuan, photographed by Feng Ye in 2007.

“In my eyes, Fangta Park is not just a combination of rivers and landscapes, but a holistic design language: the relationship between the large water surface, the large lake, the long wall and the Song Pagoda, and the small openings in each wall, as if breathing, making people feel a flowing rhythm.”

She recalled that once her father asked her to write an article, and he used only a few words to point out the core of the design—"He said that he grasped the core of the garden because it could continue the artistic conception of the Song Dynasty."

In 2007, Feng Ye photographed He Lou Xuan in the snow, capturing the essence of Song and Yuan dynasty paintings.

Although there are Ming and Qing dynasty structures in the garden, what he values most is the freedom and openness in the aesthetics of the Song dynasty, and he hopes that this sense of fluidity will run through the overall layout of the garden. He regards Fangta Garden as an open-air museum—every building and every scene is connected and supported, and they are like "pearls in the palm of one's hand," gently lifted and carefully linked together.

Fangta Garden Design Notes. Source: History Museum of the College of Architecture and Urban Planning, Tongji University.

“My father rarely expressed his feelings to me directly, but I know that his ideas for designing Fangta Garden and his gentle persistence were intertwined with his life experiences,” Feng Ye said. “At that time, I had been away from China for a long time, and he missed me. His care was not in words, but in his dedication to Fangta Garden, in his heartfelt care for Helouxuan, and in his occasional unexpected phone calls.”

That was a scene in Feng Jizhong's life. It was also a profound and tender concern he gave to his only daughter.

In the "Feng Jizhong Research Room", the original bamboo materials that were replaced during the major renovation of He Louxuan in 2021, along with the statue and calligraphy of Feng Jizhong, are displayed.

The father's tenderness was most clearly reflected in a small cardboard box.

That was when Feng Ye was six or seven years old, living in an old house at the intersection of Changle Road and Xiangyang South Road. In the spring, it was popular for children to raise silkworms. Feng Ye also bought two or three cartons from the tobacco shop, secretly put them in a glass jar of jam, stuffed a few leaves inside, and dared not let the adults know.

When her father found her that night, she expected to be scolded, but she didn't hear a single word of reproach.

When she woke up the next morning, she saw a neat, clean white cardboard box on the table, shaped like an architectural model. The box had small, evenly spaced holes for the silkworms to breathe, and the lid was shaped like a leaf. Her father said that because her name was "Feng Ye" (meaning "Feng Leaf"), he wanted to make her a "leaf" that belonged only to her.

At that time, my father was at the busiest of his career: proposing the "Principles of Architectural Space Composition (Spatial Principles)," taking students to the countryside, supervising graduation projects, and squeezing onto a bus for an hour and a half every day to get to Tongji University. But he still spent one evening making a small "building" for his daughter. He patiently taught her how to pick mulberry leaves, how to wash them, and how to gently place them in the box, telling her, "You can keep them, but you must respect them. Since you've chosen to keep them, you must be responsible for them."

Later, the silkworm spun its cocoon, emerged, and flew out of the box. The box disappeared during moves and life's changes, but it never faded from my memory.

Looking back years later, Feng Ye understood that what her father taught her with that cardboard box was far more than just the rules of raising silkworms—it was a sense of responsibility, love, and respect for life; it was also his way of doing things as an architect, doing his best within his capabilities no matter how small the matter.

That small "building" made of cardboard boxes wasn't built for the world, but for my daughter. "In that moment, I truly felt for the first time that architecture isn't just about steel bars and concrete; it also contains tenderness," Feng Ye said.

Feng Jizhong and his family of three

Tongji University's 63 Years: Conveying Its Most Mature and Insightful Thoughts

In 1947, after returning to China, Feng Jizhong began teaching at Tongji University. In his early years, he taught architecture courses in the Department of Civil Engineering. After the reorganization of departments in 1952, he continued to teach in the Department of Architecture and later the College of Architecture and Urban Planning for 63 years. He served as the head, honorary head and honorary dean of the Department of Architecture for a long time, devoting himself to the gradual development and growth of Tongji's architectural discipline.

Feng Jizhong at work. Photo provided by Feng Ye.

What few people know is that he was promoted to professor as soon as he entered Tongji University, which was extremely rare at the time. In any academic system, it takes many years to rise from teaching assistant, lecturer, associate professor to professor. However, Feng Jizhong was recognized by the domestic academic community because of his qualifications as an engineer and senior architect in Germany before the war, as well as his many years of practical experience.

Feng Jizhong was both an architect and a civil engineer. He and I.M. Pei were classmates at St. John's School and even lived in the same dormitory. Their choice to study architecture was almost entirely inspired by the same building—László Hudec's Grand Cinema and the International Hotel. That profound experience solidified their resolve: "We must do something for China."

In 1981, Feng Jizhong (right) with I.M. Pei and Chen Congzhou at Tongji University. Photo courtesy of the College of Architecture and Urban Planning, Tongji University.

In an era without computers and modeling software, he and his colleagues relied on set squares, compasses, and slide rules to measure and draw bit by bit. Feng Jizhong's ambition never wavered. After joining Tongji University, he not only taught architecture but also dedicated himself to system construction, ultimately forming a complete academic structure encompassing architecture, urban planning, and landscape architecture. In those days, such forward-thinking ideas often encountered resistance, but Feng Jizhong remained steadfast and resolute. However, given the circumstances of that era, his life was inevitably fraught with difficulties.

“I often feel sad about this because with his talent, he could have gone much further. But he remained calm. I have heard a recording of an interview he gave in his later years, in which he said that he had always had a clear conscience, was ‘not afraid, not daunted,’ and would continue to do what he believed was right. He was not defeated by any setbacks and continued to walk his own path,” Feng Ye said.

In 1981, Feng Jizhong with I.M. Pei and Chen Congzhou at Tongji University. (Photo courtesy of the College of Architecture and Urban Planning, Tongji University)

As the head of the Department of Architecture at Tongji University at the time, Feng Jizhong was adept at recognizing and appointing talent, always placing each person in the most suitable position. Those with a strong foundation in classical Chinese were responsible for the history of ancient Chinese architecture, while those fluent in English and Western history taught the history of Western architecture. "As for himself—although his training at the Vienna Polytechnic made him very knowledgeable about the history of Western architecture, he never took the initiative to say, 'I'll do this.'"

In the mid-1950s, Feng Jizhong spoke at a teaching conference. (Source: History Museum of the College of Architecture and Urban Planning, Tongji University)

Among them, Mr. Chen Congzhou's promotion left a particularly deep impression on Feng Ye. Her father rarely talked about school administration, only about scholarship. But that time, he came home and quietly said, "After all these years, he should be promoted when he deserves it." "Back then, there were few spots available, and there was some controversy. He heard there was resistance, and he only said that one sentence." In Feng Ye's view, this is the gentlemanly spirit of the older generation of intellectuals: they don't compete, they don't fight, they don't boast, but at crucial moments, they always speak a fair word.

As a teacher, Feng Jizhong would answer any questions asked without reservation. If he had a large class the next day, he would prepare for it the entire night before. According to Feng Ye's recollection, his family lived in Zhonghe Apartment at the intersection of Maoming South Road and Nanchang Road. "The apartment wasn't big; I slept in the living room. There was a small enamel table in the kitchen, bought from a secondhand market. Before each class, he would clean that table thoroughly and prepare for the lesson there all night. The next morning at five or six, he would slam the door shut and rush to catch the bus to Tongji University."

In 1986, Feng Jizhong spoke at a teaching conference at Tongji University. (Source: History Museum of the College of Architecture and Urban Planning, Tongji University)

“He never wanted to ‘leave his views in a book,’ and he was always willing to promote young people,” Feng Ye said. “The course ‘Principles of Space’ was first proposed by my father in the 1960s. He first taught it to the young teacher Zhao Xiuheng, who then taught it to first-year students. Later, some students even wrote articles saying, ‘It’s so advanced to hear such a course in first grade.’ This approach of first cultivating a team and then having the team teach students was something he always insisted on. In his mind, the most important thing for an educator is to convey their most mature and insightful thinking,” Feng Ye said.

Old photographs displayed in the "Feng Jizhong Study Room" of the College of Architecture and Urban Planning at Tongji University.

In mid-November, Feng Ye donated a batch of Mr. Feng Jizhong's academic archives to the College of Architecture and Urban Planning of Tongji University, including his work notes, reading notes, manuscripts, design sketches, interview recordings and videos, and scanned copies of engineering drawings for projects such as Songjiang Fangta Park.

Tongji University's "Feng Jizhong Research Room" unveiled

Among these materials, Feng Ye particularly admired the densely packed small handwriting in his father's notebooks. For example, one notebook recorded the concept of "holistic protection of Jiuhua Mountain," which was first proposed by Feng Jizhong.

This notebook meticulously records the layout and architectural style of every temple on Mount Jiuhua, paying particular attention to how Hui-style elements are integrated into religious architecture. The neat and uniform handwriting reflects the "military-style discipline" he developed from his student days. His notes, whether meeting minutes, random thoughts, or observations from the site, are all clearly traceable.

Feng Jizhong's manuscripts are displayed in the "Feng Jizhong Research Room".

These notes also reflect Feng Jizhong's foresight. He clearly noted which buildings should be preserved as they were, which could be modified, and which could be updated under specific conditions.

Among his companions at the time was Ruan Yisan, a student now hailed as the "Guardian of the Ancient City." In a speech in 2003, he discussed the planning of Jiuhua Mountain in 1978, pointing out that the planning principle proposed by Mr. Feng Jizhong, "restoring the old as it was to preserve its authenticity," completely protected the appearance of the Hui-style mountain village Buddhist kingdom, limited the height and size of buildings, and applied for nine temples to be designated as national-level cultural relics protection units, trying to preserve as much of the original as possible. However, in the early 1990s, when Jiuhua Mountain was applying for World Cultural Heritage status, Ruan Yisan went to visit again and found that all nine original national-level cultural relics protection units of temples were gone, replaced by some tall reinforced concrete glazed tile buildings, which was heartbreaking.

Feng Jizhong at the Xingshengjiao Temple Pagoda (Fangta) in Fangta Park in the late 1970s. Photo provided by Feng Ye.

In fact, as early as the late 1940s, while working at the Nanjing Urban Planning Commission, Feng Jizhong began to attempt to draft regulations on the protection of historical buildings in China. At that time, there were almost no established standards in China. Feng Jizhong realized that historical buildings do not exist in isolation; they are closely related to urban life and cultural memory, and therefore a complete system is needed to regulate their protection, renovation, and use.

Around the time of China's reform and opening up, he reiterated the idea of preserving the old city. At that time, Shanghai had an extremely high population density, and the per capita living space in the old city was shockingly small, making improvement of the living environment urgently needed. He led his students to study urban renewal plans for the City God Temple area, focusing on the lives of community residents and neighborly relations, arguing that improving living conditions was just as important as preserving the historical context. He particularly emphasized that people and neighborly relations are inherently part of urban culture, and development should not uproot all of this.

Feng Ye recalls accompanying her father to the World Congress of Architects in Denmark in the 1980s. The theme of that congress was "public participation," and each person had only 15 minutes to speak and share. Feng Jizhong spoke about his old city renewal plan for Shanghai, which he had worked on with his students, emphasizing the balance between preservation and development. "I remember that after he finished speaking, several Eastern European architects pulled him aside and said they were deeply moved because their situation was very similar to Shanghai's: the economy needed to develop, but a large number of historical buildings and traditional elements in the city had not been completely destroyed, and they were at the critical point of 'whether to preserve them'," Feng Ye recalled. "He said something that I've always remembered—people will slowly look back to find their cultural roots after their lives improve. If on that day, everything is demolished, then it will be very difficult to find them again."

However, Feng Jizhong's plan did not remain merely a "cultural slogan." He had long ago proposed "eliminating toilets" in Shanghai's old city and put forward the renovation of the sewer system. "In his planning concept, improving urban life and residents' sanitation were as important as the architectural philosophy."

Nearly 40 years later, Shanghai has finally "eliminated" the last toilet, but Feng Jizhong's advice on old city renovation and urban renewal still points to a long and arduous road ahead.

Remembering Lin Fengmian in his later years: The intersection of another thread of fate

One autumn evening in 1978, Feng Jizhong received a letter from Hong Kong. The letter read: “I am staying in a department store warehouse on Nathan Road. It is dimly lit, cramped, and the air is stale. I have been in this city for a year now, but I still can’t get used to the crowds and noise. Being alone in a foreign land, I often feel lonely and desolate. Could you let Feng Ye keep me company? I will do my best to help her succeed.” The letter was signed “Lin Fengmian”.

Soon after, Feng Ye set off for Hong Kong to accompany the 78-year-old Lin Fengmian for the last 13 years of his life.

Photographs by Feng Yejin and Shi Sheng when they were young.

The story of Feng Ye and Lin Fengmian begins with their mother, Xi Suhua. Xi Suhua studied at Fudan University and Aurora University for Women, but she did not receive systematic training in painting. After their marriage, Feng Jizhong discovered her talent for painting, encouraged her to study, and personally found her a teacher.

At the time, Tongji University was preparing to establish its Department of Architecture and needed teachers for basic art courses. They searched through a list of recommended teachers and eventually hired Chen Shengduo to teach at Tongji. Xi Suhua also studied sketching under Chen Shengduo. Later, the family moved into Tongji New Village and met other Tongji teachers such as Fan Mingti and Zhou Fangbai. Xi Suhua also audited classes at the Tongji Department of Architecture to draw, and her work was later selected for the Shanghai Art Exhibition and won an award.

“As my mother’s foundation in Western painting became more solid, my father wanted her to learn Chinese painting and planned to send her to Nanjing to study landscape painting under Fu Baoshi.” However, fate arranged another path—Feng Jizhong saw Lin Fengmian’s work on the back cover of a children’s magazine called “Little Friends.” At this time, Lin Fengmian was experiencing a career slump: he lived on a monthly CPPCC subsidy of 80 yuan, but rent alone cost 50 yuan. His works submitted to art exhibitions were even returned. “My parents didn’t know Lin Fengmian at the time, but after hearing these stories, they felt that he was a truly worthy teacher to learn from.”

The back cover of the third issue of "Little Friends" magazine in 1957 featured Lin Fengmian's work, "Water Birds."

Coincidentally, Lin Fengmian was Chen Shengduo's former principal at the Hangzhou Academy of Fine Arts, and could make an introduction, but only after Lin Fengmian's wife and daughter left China. During that time, Lin Fengmian was very depressed because his wife and daughter were about to leave.

Ultimately, through Chen Shengduo's introduction, Xi Suhua became Lin Fengmian's student. Feng Ye recalled that everyone found it amusing at the time—a person who had won an award at the Shanghai Art Exhibition was taken in as a student by a painter who had withdrawn from the exhibition. Lin Fengmian also frankly admitted that Xi Suhua's foundation in Chinese painting was not yet sufficient and suggested that she first study traditional Chinese painting with Zhang Shiyuan.

“When I was little, my mother painted with Zhang Shiyuan, and I would run around beside her, looking at his sketches. Later, when I learned traditional Chinese painting, I also used the set of sketches that he gave my mother, which had the style of Shi Tao.”

Mr. Lin Fengmian (right) and Mr. and Mrs. Feng Jizhong

In 1968, 69-year-old Lin Fengmian was detained in a detention center on charges of being a "spy." During his four and a half years in prison, he was required to write down the name of someone who could deliver supplies to him, and he wrote down Feng Jizhong.

“We received a small yellow letter with a specific date and time written on it, saying that we could go in and bring some soap, toilet paper, clothes, and daily necessities. That was all we could bring; we couldn’t bring more. That’s how we maintained a little contact with Lin Fengmian,” Feng Ye said. “After Lin Fengmian was released from prison, he taught me to paint. He said I was his last student, his last disciple.”

In 1977, with the help of Ye Jianying, Lin Fengmian went abroad to visit relatives and eventually went to Hong Kong. A year later, he wrote back to the relevant leaders in Shanghai, saying that he was going to France to hold an exhibition and needed an assistant. So Feng and Ye were approved to go to Hong Kong.

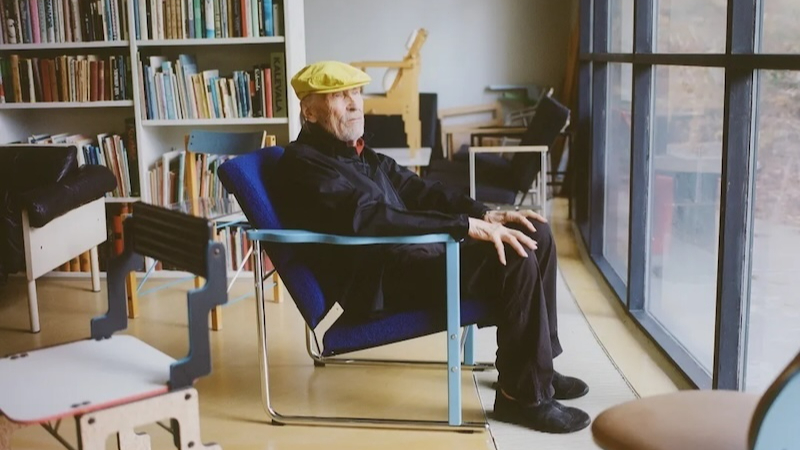

Lin Fengmian in Hong Kong in the early 1980s. (Photo by Feng Ye)

In 1979, Lin Fengmian held an exhibition at the Cernuschi Museum in Paris. "Chirac also attended that exhibition. I originally planned to stay in Paris. The president and dean of the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris saw my work and were willing to accept me as a graduate student. But I had to go back to Hong Kong to apply for a visa first and come back a few months later, which they agreed to." Feng Ye told The Paper Art. "But just during those few months, Mr. Lin suddenly suffered a severe stomach hemorrhage and was admitted to the emergency room three times. He could barely stand. Although I really wanted to continue my studies, Mr. Lin was already over eighty years old at that time. I thought about how he had suffered a lonely life and was in such poor health, and I didn't have much time left to spend with him. So I didn't go to Paris to study. I don't regret it at all."

In the late 1980s, Lin Fengmian visited Feng Ye's art exhibition and inscribed a message. (Photo provided by Feng Ye)

However, Feng Ye harbored regrets about her father, Feng Jizhong. Her later days were filled with busyness: solo exhibitions in Hong Kong, Japan, and France, and planning the centennial commemorative exhibition for Lin Fengmian, consumed almost all her time.

"If I could have stopped my own work sooner and helped my father more, perhaps he could have left behind more works, and there would have been more dialogues and academic research. His thoughts would have been more complete and systematic. This is a deep regret in my heart."

In 1998, Feng Jizhong and his family were on a Mediterranean cruise ship. (Photo provided by Feng Ye)

Special thanks to: Jimuang Media (Director: Zhou Congqi; Photographers: Huang Xiaohang, Wang Ronghai, Huang Tao)