Designed by architect I.M. Pei, Dallas City Hall, completed in 1978, is a landmark example of American Brutalist architecture. However, this 47-year-old city landmark now stands at a crossroads between restoration, sale, and demolition, sparking debate within the architectural community and heritage preservation organizations.

This debate about "economy" versus "cultural heritage" reflects the common dilemma faced by historical buildings in contemporary urban development. Similar examples include the Kagawa Prefectural Gymnasium, designed by Japanese architect Kenzo Tange, which is facing demolition; and Boston City Hall, completed in 1968, which was also proposed for demolition but was fortunately renovated and can continue to be used.

Old photos of Dallas City Hall

The Paper learned that Dallas City Hall is considered a landmark example of American Brutalism, a representative public works project completed by I.M. Pei and his team between 1972 and 1978. The building occupies approximately 11.8 acres, with a total floor area of 73,710 square meters, including three underground floors, seven floors above ground, and a partial eight-story structure.

Dallas City Hall

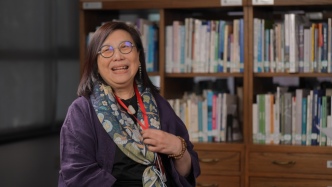

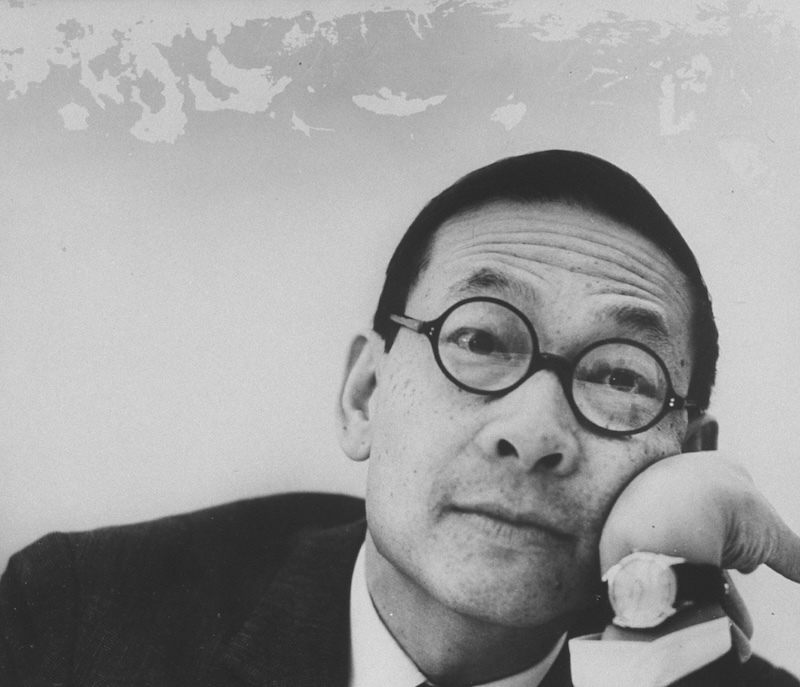

I.M. Pei

I.M. Pei employed a highly sculptural inverted pyramid shape, with the north facade tilting forward at a 34-degree angle and projecting a maximum distance of 20.7 meters. This exaggerated and dynamic composition allows City Hall to stand out prominently in Dallas's urban fabric, while also providing necessary shade for the large civic plaza in front of the building's base, offering a relatively soothing public space in the city's high-temperature environment. The building's interior houses over 374,000 square feet of office space, two levels of underground parking, council chambers, a flag room, and a large atrium. Pei described the entire project as "an inseparable combination of architecture and park," creating an open, democratic, and urbanly oriented public building.

Dallas City Hall front

Side of Dallas City Hall

At the time, many municipal institutions in the United States were trending towards isolation, but the Dallas City Hall design went against the grain, using a huge public forecourt as a container for civic activities, thus shortening the distance between the government and the people both physically and symbolically. In the 1987 film "RoboCop," this building became a cultural icon in the film, securing its special place in popular culture history.

However, due to decades of neglect, the building has fallen into disrepair, suffering from leaks and electrical system malfunctions, yet only a small portion of the city government's budget is allocated to municipal maintenance. According to *The Architect's Newspaper*, in March of this year, the local landmarks committee voted to advance the City Hall's historic landmark designation process, but in August, the mayor instructed the finance committee to reassess the "most financially responsible option," initiating a new debate. In October, the Dallas City Council voted to re-examine whether the building should continue to serve as a municipal office, while also considering relocation costs, restoration possibilities, and land development potential. In November, the debate continued, making the fate of City Hall more precarious than ever before, drawing strong attention from the architectural community and international conservation organizations. The full assessment report is expected to be released next February.

Dallas City Hall (partial view)

Dallas City Councilman Chad West believes that selling the land would free up prime downtown space for redevelopment, potentially allowing for a new arena for the Dallas Mavericks. Others, however, argue that the proposal deviates from the building's original design. Historicist Ron Siebuler told the Dallas Morning News, "This is an important part of Dallas's downtown cultural fabric. Demolishing a historic building to build an arena is typical Dallas business practice."

When Dallas City Hall was completed in 1978, the city was still struggling to shake off the national stigma surrounding the assassination of John F. Kennedy. Then-Mayor Eric Johnson envisioned a municipal building that reflected Dallas's new image—confident, modern, and imbued with humanistic concern. Many scholars believe that I.M. Pei described architecture as a "reflection of society," and Dallas City Hall embodies this concept, transforming the ideals of transparency and accessible democracy into a magnificent architectural form.

Old photos of Dallas City Hall

According to *Building News*, several conservation organizations, such as Docomomo US, have questioned the rapid pace of decision-making and insufficient public participation. They believe the city government's focus seems entirely on "maximizing the economic value of the land" rather than preserving the historically significant building. Supporters of preservation, comprised of some councilors and architectural historians, advocate for an immediate and comprehensive feasibility study for restoration and urge the city government to grant it official historic landmark status to protect this urban cultural and architectural heritage.

Those supporting demolition and relocation focus on the financial realities: enormous repair costs and continuously rising operating costs. Earlier this year, a burst water pipe flooded the council chamber. The building's repair costs are estimated to reach hundreds of millions of dollars. Some argue that the building's inherent functional defects and huge maintenance costs should not be ignored simply because of the designer's fame.

Dallas City Hall was one of Dallas's earliest attempts to make government buildings more approachable. Now, the plaza is often deserted, and the fountains are dry. City Councilwoman Paula Blackmon, who supports restoring the building, calls this neglect a failure of municipal administration. She said, "It's regrettable that we haven't taken good care of it."

Dallas City Hall from an aerial perspective

This debate over "economy" versus "cultural heritage" has left the future of I.M. Pei's masterpiece uncertain, reflecting a common dilemma faced by historical buildings in contemporary urban development. Similar cases have occurred in many places; for example, the Kagawa Prefectural Gymnasium, designed by Japanese architect Kenzo Tange, is facing demolition; and Boston City Hall, completed in 1968, was also proposed for demolition, but fortunately, it was eventually renovated and continues to be used. Some conservationists believe that the Boston City Hall restoration project proves that mid-20th-century municipal buildings are repairable.

Dallas City Hall (interior)

An opinion piece in The Architects Times stated: "The towering concrete structure of Dallas City Hall may not be universally appealing, but it is undeniably distinctive. As the city's population density increases, its economy prospers, and privatization continues to grow, the building's imposing presence becomes all the more striking. It serves as a reminder that Dallas was once committed to building a city for its citizens, not its investors."

Reagan Rosenberg of the Dallas Landmarks Council once wrote in the Dallas Morning News, "I have yet to find any of I.M. Pei’s important designs that have been forgotten by history, and I hope Dallas will not be the first place to suffer this fate."

I.M. Pei's Dallas "Fountain Plaza"

It's worth noting that I.M. Pei designed several buildings in Dallas. Besides Dallas City Hall, One Dallas Center is a sleek skyscraper with a completely glass facade. Built in 1979, it was originally an office building but was later converted into a mixed-use complex. The 49-story Energy Plaza, completed in 1983, boasts a distinctive triangular exterior, using sharp angles and reflective glass to create a dynamic visual effect on the Dallas skyline. His Fountain Plaza, a 63-story glass tower in downtown Dallas completed in 1986, features a unique prismatic shape and reflective facade that interacts with natural light, making it one of Dallas's most iconic buildings.