The Louvre Museum's first major exhibition in Shanghai, "The Miracle of Patterns: Masterpieces of Indian, Iranian and Ottoman Art from the Louvre," has been set up and will officially open to the public on December 13 at the Shanghai Pudong Art Museum.

What are the most anticipated exhibits in this major exhibition? What ingenious details were incorporated into the exhibition design? On December 10th, ArtPulse interviewed Judith Henon-Raynaud, Deputy Director of the Department of Islamic Art and Curator at the Louvre Museum, and Souraya Noujaim, Director of the Department of Islamic Art, at the exhibition site. Both repeatedly expressed their hope that visitors would view the exhibition as if opening a "jewelry box."

Three great civilizations, one "miracle"

The exhibition "The Miracle of Patterns" is the first exhibition of its kind in Shanghai by the Louvre Museum. Drawing upon the Louvre's extensive collection, the exhibition aims to showcase the artistic achievements of Indian, Iranian, and Ottoman civilizations from the 16th to the 19th centuries. Featuring approximately 300 treasures from the Louvre's collection, this is the largest exhibition the Louvre has ever held in China. When asked how these 300 works were selected, the curator chuckled, "We brought masterpieces from the 16th to the 19th centuries."

The exhibition is divided into three main sections, showcasing numerous artistic masterpieces from India, Iran, and the Ottoman Empire. As the exhibition title suggests, the art of these regions is renowned for its unique and rich pattern aesthetics, such as natural flowers, poetic imagery, and geometric patterns. These patterns not only reflect the cultural and historical context of their time but also infuse new concepts and methods into later art and design. These patterns can still be seen in contemporary jewelry, architecture, bookbinding, decoration, and graphic design. Transcending time and place, they continue to inspire creation across generations, a truly remarkable feat.

Souraya Noujaim, Head of the Department of Islamic Art at the Louvre Museum, and Judith Henon-Raynaud, Deputy Head of the Department of Islamic Art and Curator.

Curatorial Highlights: Viewing the exhibition like opening a "jewelry box"

This exhibition occupies two floors of the Pumei Art Museum. The third floor showcases art from India and Iran, while the fourth floor displays Ottoman masterpieces. "Some of the exhibits are quite small, and from the exhibition layout perspective, we wanted to design a feeling of opening a jewelry box," said curator Judith. She revealed that the Louvre's Islamic Department is currently closed for redesign and is expected to reopen in 2028. This exhibition in Shanghai represents a new experiment, "for example, in the design of the circulation routes, we also hope to gain inspiration and find common ground." Because the Islamic Department is currently undergoing renovations, this exhibition is a rare opportunity for Shanghai audiences.

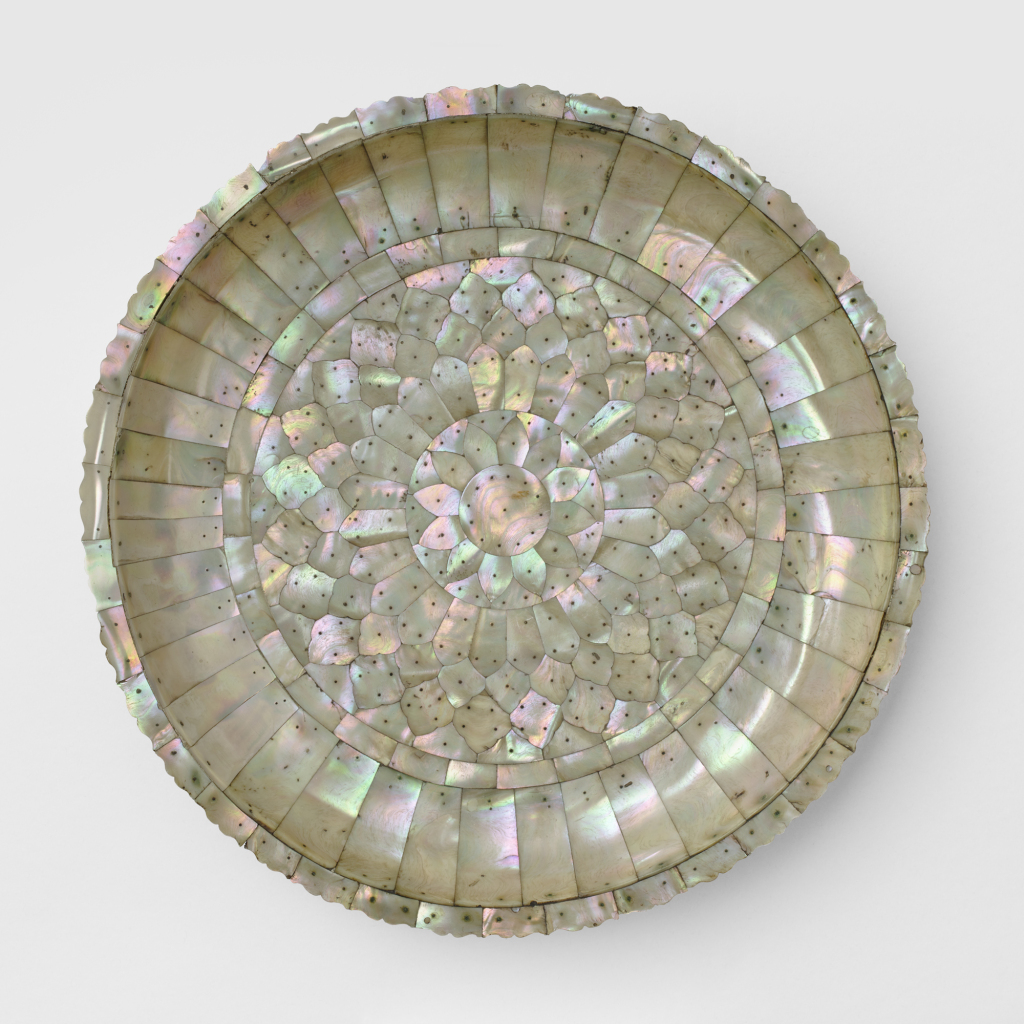

Indian mother-of-pearl assembly, metal core, copper-studded ewer, circa 1585–1615: 33 cm high; tray: 35.5 cm in diameter. © 2024 Musée du Louvre, dist. GrandPalaisRmn / Hervé Lewandowski

Indian mother-of-pearl, circa 1585–1615, metal © 2024 Musée du Louvre, dist. GrandPalaisRmn / Hervé Lewandowski

The curator specifically mentioned a set of exhibits—a ewer and a tray—which is the Louvre's newest acquisition and is being shown to the public for the first time.

The main structure and decorative parts of this exquisite set are all made of mother-of-pearl. Such objects were first transported to Goa, often adorned with silver mortises, and subsequently exported to Europe, the Middle East, and Indonesia. The ewer's shape has distinctly Indian characteristics, suggesting it may have originally been made for Indian nobility or exported to the Ottoman Empire.

How civilizations interact and integrate is a key theme of this exhibition. "We hope that visitors will approach the exhibition with an open mind and not need to do any research." In fact, the shapes of the porcelain pieces and the patterns of blue and white porcelain seen at the exhibition will likely give visitors a sense of déjà vu.

Turkish glazed ceramics, circa 1510 © 2009 Musée du Louvre, dist. GrandPalaisRmn / Hughes Dubois

For example, the bowl above was produced in Iznik, a major ceramic center in the Ottoman Empire. The white decoration on the cobalt blue background is inspired by Yuan dynasty blue and white porcelain. In the Ottoman court, elegant and luxurious objects were highly sought after.

Turkish glazed ceramics, circa 1560–1575 © 2009 Musée du Louvre, dist. GrandPalaisRmn / Hughes Dubois

This red cup features a staggered floral pattern, and its bright coral red color breaks away from the prevailing blue and white color scheme of the time, representing a typical abstract treatment of natural elements in Islamic art.

"The influence of Chinese patterns on Islamic art began as early as the Middle Ages, especially after the development of maritime trade, which led to more frequent communication. In the 16th and 17th centuries, a great deal of ceramics reached Islam via sea and land. At that time, porcelain was a luxury item, owned only by royalty and nobility. It was during this period that Iran's ceramics industry flourished. Chinese porcelain naturally became an important fashion trend. Therefore, the influence of Chinese porcelain on Iranian porcelain can be seen in the exhibits," Judith noted. She added that in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, the French gradually began to understand Islamic art, and these patterns brought them an aesthetic appeal, leading to varying degrees of borrowing and inspiration from them.

Iranian 17th-century glazed ceramics © 2025 Musée du Louvre, dist. GrandPalaisRmn / Raphaël Chipault

The dragon-patterned vase above is influenced by Eastern art; the original Chinese ceramic design was cleverly transformed, becoming an important part of the Safavid artistic vocabulary. It reflects the exchange and fusion of the "dragon" element in Islamic and Chinese cultures. In the 17th century, the establishment of the British and Dutch East India Companies and the export of Iranian pottery to Europe further disseminated ceramic culture.

“When Iranian ceramic workers saw dragon patterns on Chinese ceramics, they imitated them. Dragons can also be seen on Iranian ceramics in the 19th century. However, the lines of the Chinese dragons were more fluid. After they were passed down, the image of the dragon changed and the lines became more angular. Although it was only the beginning of globalization at that time, we can see the impact of globalization on works of art from these details.”

Dagger with horse-head hilt, 17th century India, steel, jade, gold, rubies, emeralds © 2010 Musée du Louvre, dist. GrandPalaisRmn / Hughes Dubois

On display at the exhibition is a beautifully crafted dagger with a horse-head handle. Judith hopes visitors will pay close attention to the details of this piece. "You can see the detailed forms of the horse's teeth and tongue, and the dagger's shape is also very typical, showcasing the artistic style of the Mughal dynasty. The use of a horse as decoration demonstrates the importance of the horse in Islamic civilization, and the fact that it's carved from jade shows that such a meticulously crafted dagger was used to symbolize victory and also reflects the status and position of its owner."

Turkish glazed ceramics, circa 1540–1555 © 2010 Musée du Louvre, dist. GrandPalaisRmn / Hughes Dubois

Another piece worth examining closely is a peacock-patterned plate. The small, round plate depicts a breathtakingly beautiful, fantastical garden. Bird motifs are extremely rare on vessels from the same period, making this piece particularly precious. Peacock patterns also exist in China, "but the peacock has different symbolic meanings in different civilizations. For example, in the Safavid dynasty of Iran, the peacock represented royal power."

Book cover with "Rose and Nightingale" design, Iran, 1775-1825, concrete paper, lacquer © 2012 Musée du Louvre, dist. GrandPalaisRmn / Hughes Dubois

In Islamic art, book decoration occupies an important position, and the gorgeous and exquisite animal and plant patterns reflect the humanistic spirit. The representative theme "Nightingale and Rose" uses objects to express emotions and convey a romantic narrative.

According to Judith, many motifs like roses and nightingales are inspired by Chinese Song Dynasty paintings, especially flower-and-bird themes, which were very popular in the 19th century because they were so moving. Islamic artists then incorporated flowers and birds into their motif repertoire. "In Iran, the theme of nightingales and roses also frequently appears in poetry, depicting the relationship between lovers and their beloved. The nightingale searches for its lover—the rose—but when it gets close to its beloved, the rose's thorns hurt it. This embodies the duality of love—the coexistence of pleasure and pain."

Royal tastes and their influence on contemporary aesthetics

"This exhibition features a diverse range of categories and a modern aesthetic, and we hope it will attract more young viewers," said Suraya, Director of the Islamic Art Department. She added that these patterns can also be found in some fashion brands, influencing contemporary design and continuing this aesthetic to this day.

Indian or Iranian walrus ivory, gold, brass, turquoise, black filler, circa 1586–1588 © 2018 Musée du Louvre, dist. GrandPalaisRmn / Hervé Lewandowski

For example, the pen case pictured above, engraved with the name of Abbas the Great of the Safavid dynasty (reigned 1587-1629), was once part of the collection of the famous jeweler Louis Cartier. Its profound influence can be seen in numerous design drafts and finished products.

Louis XIV, the third king of the French Bourbon dynasty in the 17th century and known as the "Sun King," had a great passion for art. His collection of art masterpieces from all over the world played a crucial role in the development of the French royal collection. Among these were various precious artifacts from ancient times, the Ottoman Empire, and the Mughal Empire, which constituted the first batch of artworks from the Islamic world to enter the royal collection.

Before becoming part of the French national collection, these artifacts adorned the Louvre, the Tuileries Palace, and the Palace of Versailles, showcasing the aesthetic tastes of the most prosperous period in French art development. In this major exhibition, visitors will also have the opportunity to admire some of the Islamic art treasures "personally selected by the King."

This collection includes four pieces from the royal collection: three from Louis XIV and one from Napoleon.

Turkish cup, mid-16th century, made of jade, gold, and rubies © 2009 Musée du Louvre, dist. Grand Palais Rmn / Hughes Dubois

Upon entering the exhibition hall, you will see a jewel-encrusted cup from the collection of Louis XIV. Originally exhibited at Versailles, this cup entered the Louvre in 1796 and is a masterpiece of Ottoman hard-stone inlay craftsmanship.

Regarding the provenance of the royal collection, according to Suraya, some were diplomatic gifts of the time. "During the reign of Louis XIV, relations between nations became more organized and structured." Besides royal commissions, the large number of tourists traveling to the East in the 19th century also spurred artistic exchange. "Perhaps many people overlook this, but in the late 19th century, Paris became an important center for the development of Islamic art. At this time, the discipline of Islamic studies emerged, along with the Paris Academy. The decades that followed saw continuous development, giving rise to a trend called Art Deco, and geometric patterns had a very significant influence on Art Deco."

Interior of the Islamic art galleries on the second and third floors of the Louvre Museum, dating from 1922 © Musée du Louvre/Archives DAI, PAI 831

The Louvre's earliest collection of Islamic art dates back to the museum's founding in 1793. In the 17th century, during the reign of the "Sun King" Louis XIV, art from the Islamic world first entered the French royal collection. In the late 19th century, the Louvre archives first recorded a dedicated gallery for Islamic art. Over the next century, this part of the Louvre's collection moved between different departments and locations amidst historical upheavals. Despite experiencing two world wars, this collection continued to expand and improve through the efforts of various individuals. In 2003, the French Ministry of Culture established the Department of Islamic Art, officially becoming the Louvre's eighth department and the fifteenth department within the French National Museums Union. Today, the department holds 14,000 pieces, plus 3,500 works on deposit from the Musée des Arts Décoratifs.

Its distinctive feature is its rich collection, encompassing diverse media. These include metalware and inlaid gold and silver artifacts, jade carvings, glassware, ivory artifacts, as well as various glazed pottery, textiles, carpets, silks, calligraphy, and manuscripts. Because of this diversity, the exhibition also recreates two display rooms, allowing visitors to immerse themselves in the spirit of the times embodied in these artworks.