The Paper Art Review will soon launch a series of articles titled "Artists in Shanghai." Using artists' studios as a clue, the series will get closer to artists living in Shanghai, allowing us to experience their daily lives, creations, and thoughts. This issue features an interview with artist Ding Yi in his new studio on Fuxing Island in Yangpu District, Shanghai.

Before the Spring Festival this year, Ding Yi completed the renovation of his new studio at the former site of the China Shipyard on Fuxing Island. He immediately devoted himself to creation, preparing works to be exhibited in Yunnan later. Currently, these works are being exhibited in "Winding Mountain Road" at the Contemporary Art Museum in Kunming, Yunnan.

From the banks of Suzhou Creek to West Bund, and now to Fuxing Island in the Huangpu River, Ding Yi's studio's relocation history reflects the rhythm of Shanghai's urban development and closely echoes the nearly four-decade evolution of his "Ten Indications." Through this series of works, one can not only understand the artist's personal exploration but also feel the reflection and influence of Shanghai's cultural charisma.

Artist Ding Yi works in his studio on Fuxing Island. (Photo by Huang Song, The Paper)

Fuxing Island, the only inland island on the Huangpu River, is accessible by the Dinghai Road Bridge, akin to a time tunnel. On one side lies the Yangpu Riverfront, while the other, a fleeting moment, transports you back to the industrialized 1980s. The island boasts a single road, flanked by towering trees and shrouded by factories and docks, creating a time capsule that captures the city's history yet remains isolated from the hustle and bustle of the city.

A studio converted from an old factory building at the China Shipyard on Fuxing Island. (Photo by Huang Song, The Paper)

As has been his custom for many years, Ding Yi returns to his studio after lunch to discuss daily tasks with his assistant. Then, in the evening, he enjoys his solitude, immersed in painting, until leaving around 3 or 4 a.m. the following morning.

Compared to his previous work on the West Coast, the "psychological distance" between Fuxing Island and the city creates a quieter work atmosphere. Here, Ding Yi completed many of the works for his solo exhibition, "Winding Mountain Road," currently on view at the Museum of Contemporary Art Kunming and the Yunnan University Museum of Anthropology.

A panoramic view of Ding Yi's studio on Fuxing Island. Photo by Alessandro Wang, courtesy of Ding Yi Studio.

Reinterpreting the Naxi "Divine Road Map" with local experience

Beginning with his 2022 Summer Tibet exhibition, Ding Yi has embarked on a series of works incorporating local contexts: Tibet, Qingdao, Shenzhen, Ningbo, and now Yunnan. These locations, like puzzle pieces, form a concept of geography, embedded within Ding Yi's "Ten Indications" system, which has persisted for over thirty years.

In the winter of 2021, Ding Yi traveled to Tibet to research his solo exhibition, "Ten Directions: Ding Yi in Tibet," at the Jibengang Art Center and Xideling Monastery in Lhasa. Image courtesy of Ding Yi Studio.

In reality, these puzzle pieces aren't isolated. For example, Tibetan works depict the vast plateau landscape and the spiritual power of religion, creating a striking visual impact. Yunnan and Tibet are geographically situated within the same Hengduan Mountains and Himalayas. Historically, the Naxi and Tibetan peoples share a common ethnic origin and share a deep connection with the Tibetan Bon religion.

The exhibition "Ding Yi: Winding Mountain Road" at the Yunnan University Museum of Anthropology features a Naxi scroll called "Divine Road Map." Image courtesy of the Kunming Museum of Contemporary Art.

The creative process is like an adventure. Over the past year or so, Ding Yi has traveled to Yunnan three times, starting with the Lijiang Dongba Cultural Research Institute and continuing on from Lijiang, Shangri-La, Deqin, Xiaozhongdian, Yubeng Village, and Songzanlin Monastery. After conducting cultural research in Yunnan, he gradually settled on Naxi culture as his primary creative direction. But how can one interpret and respond to Dongba culture through the language of contemporary art, rather than simply extracting a few elements of this minority?

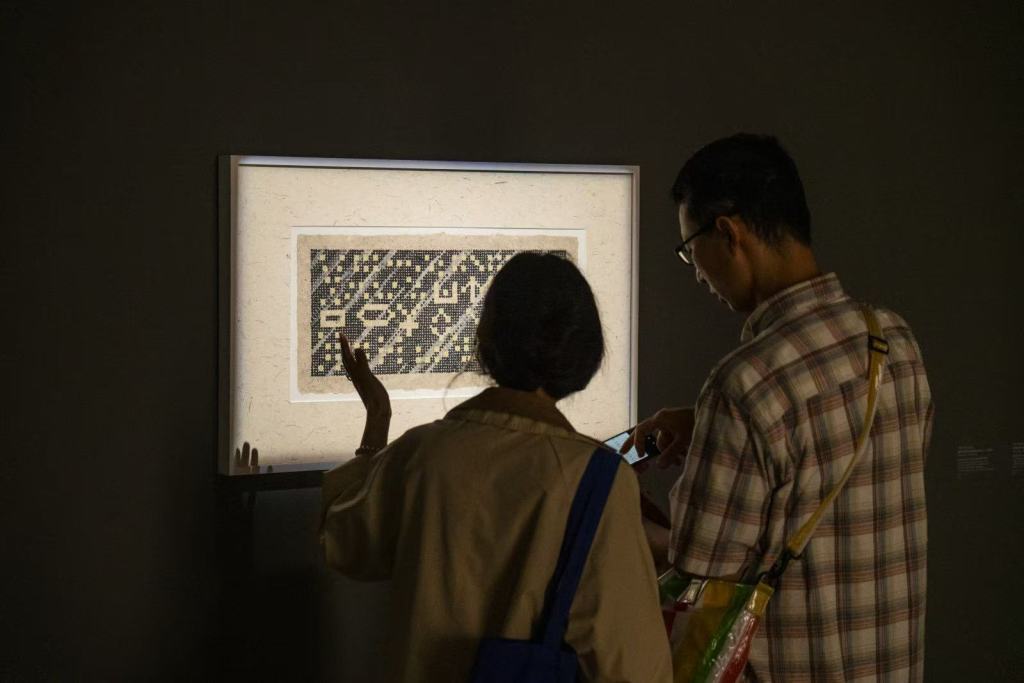

The exhibition "Ding Yi: Winding Mountain Road" at the Kunming Contemporary Art Museum shows the first section, "Divine Road Map." Image courtesy of the Kunming Contemporary Art Museum

The exhibition "Winding Mountain Road" seems to respond to this reflection. A painting, "Divine Road Map," stretching infinitely upward, occupies the centerpiece of the exhibition hall. As an ancient scroll from the Dongba religion of the Naxi people, "Divine Road Map" serves as a spiritual map for the ascent of the deceased: it guides souls across nine black rivers, over nine mountains, through the realm of the dead and punishment, back into the human world, and ultimately to the Pure Land and the realm of the gods. Ding Yi reweaves this spiritual journey in abstract language, symbolizing key figures: seven golden mountains, thirteen suns and moons, thirteen cypress trees, and thirty-three temples... These accumulated figures create a new visual order, replacing the original narrative imagery.

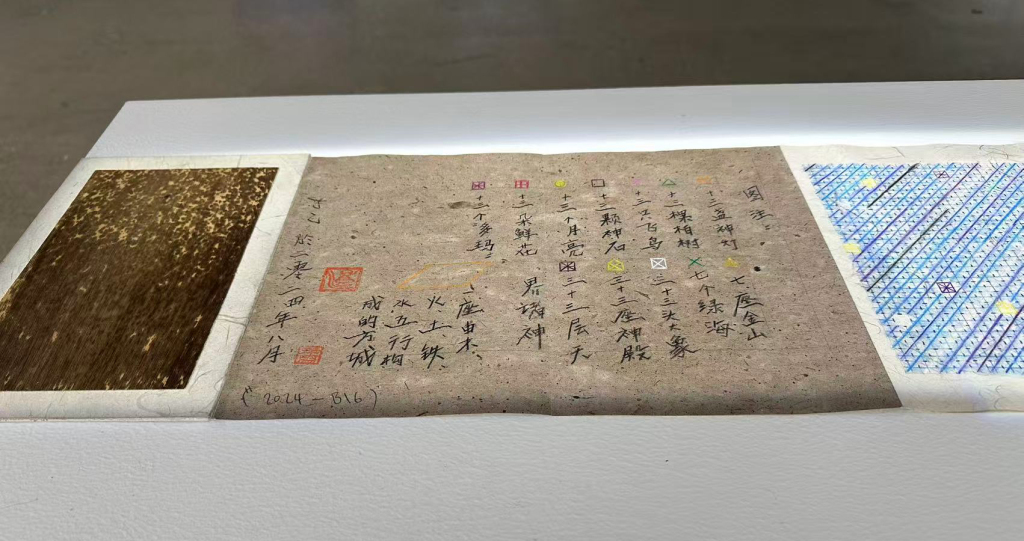

At the exhibition, a scroll of "Divine Road Map" painted on Dongba paper has numbers at the end corresponding to abstract symbols. (Photo by Huang Song, reporter of The Paper)

However, Ding Yi was apprehensive about reinterpreting "The Divine Road" in his own pictorial language. To this end, he sought advice from Bao Jiang, a researcher at the Institute of Sociology of the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences. He also visited He Hong, a researcher at the Lijiang Dongba Cultural Research Institute, and Duoji, director of the Lugu Lake Mosuo Museum. However, Ding Yi's initial attempts were not without errors. He excitedly painted a horizontal scroll of "The Divine Road" using Dongba paper album leaves he had purchased in Lijiang. However, when he took his work to Naxi scholar Bao Jiang for advice, he acknowledged the transformation but pointed out that "The Divine Road" was never horizontal, but rather vertical, because it is essentially a channel for the soul's ascent. "This reminder touched me deeply," Ding Yi said. "At the time, I had not studied Naxi culture in depth and was simply painting out of passion. But the scholar's advice made me realize that I must respect its logic, and so I created the second, vertical scroll of "The Divine Road."

Ding Yi discusses his work with friends at the opening ceremony of "Winding Mountain Road." Image courtesy of Kunming Contemporary Art Museum

To further understand Naxi culture, Ding Yi bought numerous books and listened to podcasts. On his third trip to Yunnan in late autumn last year, he brought a small film crew and invited Tibetan director Wanma Zhaxi to direct a documentary. Two cars, traversing mountains and ridges, reached Youmi Village in Labo Township, Ninglang County, where He Hong had previously conducted field research. This well-preserved Naxi village is a three-hour winding road from Lugu Lake. With no inns, they stayed at the home of Yang Shigu, the old Dongba, and constantly sought guidance from this wise man who presided over rituals. In the village, Ding Yi observed that different Naxi villages adhered to the same scriptural model and sacrificial traditions, closely linking the order of the universe, the gods, and humanity.

Exhibition view of "Ding Yi: Winding Mountain Road" at the Kunming Museum of Contemporary Art. Image courtesy of the Kunming Museum of Contemporary Art.

This field experience allows his creation to move beyond mere visual borrowing. Continuing Ding Yi's previous explorations in Tibet, through a process of exchange, revision, and rethinking, he transforms art into a dialogue between cultures. He also expands his artistic language through the intertextuality between symbolic order and local culture.

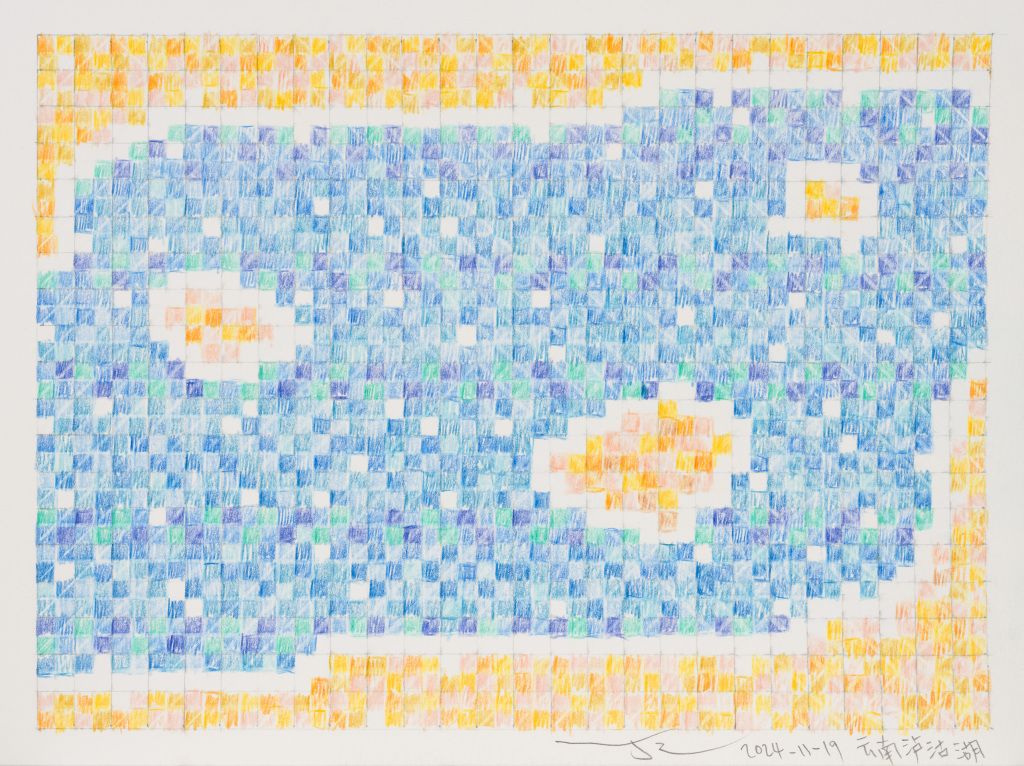

Ding Yi, “Travel Notes, Lugu Lake, Yunnan,” water-soluble colored pencils on sketchbook, 20.8 x 29.5 cm, November 19, 2024. Image courtesy of Ding Yi Studio

For his solo exhibition, which will be held in London in September, Ding Yi will once again choose works from the Yunnan series and will also bring a documentary directed by him to Wanma Zhaxi, providing European audiences with local cultural background and attempting to convey this experience of the Naxi people to audiences further afield.

The documentary "Divine Road" is being shown at the "Ding Yi: Winding Mountain Road" exhibition at the Kunming Contemporary Art Museum. Image courtesy of the Kunming Contemporary Art Museum

The connection between the aftertaste of Chinese painting and contemporary art

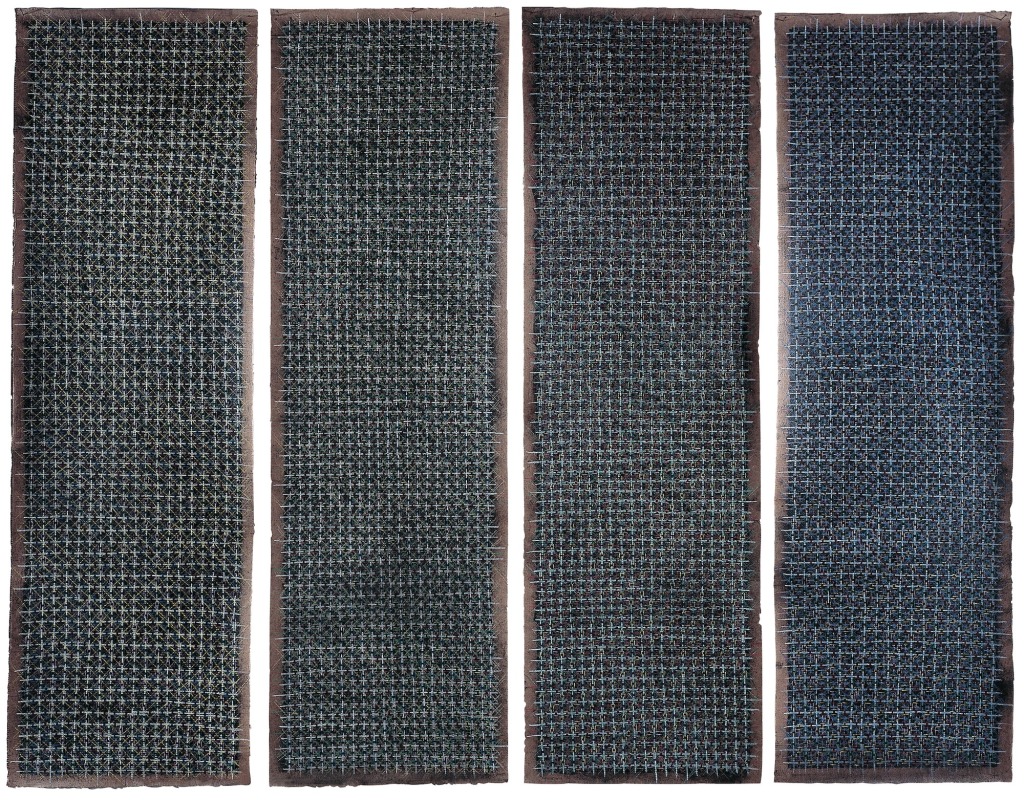

In conjunction with his solo exhibition in London, Ding Yi will also hold a conversation with experts from the British Museum's Asian Department on October 3rd. This conversation stems from a 2013 album leaf by Ding Yi titled "Seventy Circles," currently on display at the British Museum. Coincidentally, the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York recently acquired his four-panel scroll on corrugated paper, "Ten Signs 1997-B26-B29," from 1997. Both of these forms are deeply imbued with Chinese imagery.

Ding Yi's "Seventy Circles," a permanent exhibition at the British Museum, is located in the lower right corner of the display case. Image courtesy of Ding Yi Studio

Few people know that Ding Yi graduated from the Traditional Chinese Painting Department of the Shanghai University Academy of Fine Arts, and primarily uses a wolf-hair brush. Ding Yi recalls that the department had only five students back then, but was equipped with numerous renowned teachers—Ying Yeping taught landscapes, Qiao Mu taught flowers and birds, and calligraphy and seal carving classes were taught directly at the Shanghai Chinese Painting Academy. However, within this traditional "teacher-apprentice" teaching method, Ding Yi began to reflect on whether, in the face of the revitalized urban landscape, the ancient painting system could still respond to the rapidly changing social realities of the reform and opening up.

Before enrolling in the Chinese Painting Department in 1986, Ding Yi studied design at the Shanghai Institute of Fine Arts and was subsequently assigned to work at a toy factory. This experience introduced him to the intellectual framework of "Modernism" at an early age, which he gradually understood through his study of the "Paris School." However, he remained virtually ignorant of traditional Chinese culture. Consequently, he had a clear ambition: to lay the foundation for a potential future path of "fusion of East and West" through his four years of Chinese painting studies.

Ding Yi, “Cross 1997-B26-B29,” charcoal and chalk on corrugated paper, 260 x 80 cm x 4 cm, 1997, Collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Image courtesy of Ding Yi Studio.

Ding Yi also attempted to explore new possibilities in ink painting, but gradually realized that it would be difficult for Chinese painting to return to the glory of the Song and Yuan dynasties, as the spirit of the times and social structures had fundamentally changed. He therefore turned to rational painting, beginning to construct images in a more personal way. As early as the late 1980s, he wrote in his journals: "I will neither inherit Chinese tradition nor Western modernism, but will forge a new path." Initially, this seemed like a declaration, but as his horizons broadened and his participation in international exhibitions increased, his "path" gradually became clear in practice: finding a creative language within a self-awareness and a global context.

Exhibition view of Ding Yi: Winding Mountain Road. Image courtesy of Kunming Contemporary Art Museum

Despite this, the influence of his Chinese painting training persists, lurking within his art. For example, he still habitually paints with a brush, even when dipped in acrylic paint. He frequently uses album leaves, rice paper, fans, and screens as mediums, and has even recently experimented with movable type printing. In these experiments, the relationship between ink and water is expressed through charcoal, chalk, and acrylic.

As Ding Yi said, “Invisibly, the profession you once studied still radiates a certain energy, creating a dialogue and connection with the present.”

A corner of Ding Yi's studio. Photo by Huang Song, a reporter from The Paper.

The intertextuality between “Ten Signs” and Shanghai’s cultural ecology

Ding Yi began his "Cross" paintings in 1987, subsequently progressing through three phases: "Looking Straight," "Looking Down," and "Looking Up." "Looking Straight" corresponds to a modernist gesture—the symbolic "cross" is repeatedly deployed, becoming a personal visual language constantly exploring the flat surface. "Looking Down" is closely tied to the city of Shanghai. Around 2000, Shanghai's urbanization revived the symbolic meaning of the "cross" in reality. This was a period of rapid urbanization in China, with Shanghai's skyline constantly being reshaped. Urban expansion, economic prosperity, and the rhythms of urban life permeated his paintings, shrouded in fluorescent colors. After this "looking down" on the city, Ding Yi shifted his practice to a broader vision of civilization through "looking up." Travel became his method, and the cultural attributes and historical depths of different regions forced "Cross" to break away from the framework of a single dialogue between China and the West and embrace a broader global perspective.

The exhibition at the Kunming Contemporary Art Museum also reviews the history of the "Ten Crosses." Image courtesy of the Kunming Contemporary Art Museum

During the creation of "Ten Representations," Ding Yi's studio moved seven or eight times. From Wujiaochang and Daduhe Road to the Suzhou Creek, then to the West Bund and Fuxing Island, each studio shift was not only a spatial adjustment but also a resonance with the rhythm of Shanghai's development. The city's expansion, renewal, and transformation have in turn driven the different stages of "Ten Representations"—from "looking straight," "looking down," and "looking up" to the more recent exploration of "spirituality," always in causal connection with Shanghai's cultural context.

Ding Yi's Zhengsu Road Studio, 1983-1986. Image courtesy of Ding Yi Studio.

Ding Yi's studio on West Suzhou River Road, 1999-2002. Image courtesy of Ding Yi Studio.

"Shanghai is a city that has truly experienced the baptism of modernism," Ding Yi said. From Lin Fengmian, Liu Haisu, and Wu Dayu to Chen Junde and Chen Yifei, Shanghai painting has a remarkably clear modernist vein, a trait not often seen in other Chinese cities. This cultural foundation has endowed Shanghai artists with a natural "Shanghainess"—openness, inclusiveness, and internationalism. Artists transcend the self-imposed limitations of their local communities and instead cast their vision directly upon the world.

Ding Yi West Bund Studio, 2015-2024. Photo: Alessandro Wang. Courtesy of Ding Yi Studio.

This "Shanghainess" is also reflected in the city's art ecosystem. The city was home to some of China's earliest galleries, and the earliest experiments in art markets and auctions took place here. Today, Shanghai hosts two major art fairs every November, and boasts a diverse network of public and private art institutions, including the Power Station of Art, the Pudong Art Museum, and the Long Museum. Together, these diverse art ecosystems foster a vibrant scene.

Ding Yi works in his studio. Photo by Huang Song, a reporter from The Paper.

As an artist who has long lived and worked in Shanghai, Ding Yi has consistently emphasized the relationship between the city and its creative ecosystem. Now, as "Cross" has progressed nearly four decades, Ding Yi seeks to guide it in a new direction—a pursuit of "spirituality." This phase is a continuous search. How can one imbue his work with true spiritual power? How can one still resonate in contemporary society? These are questions the artist is constantly willing to take risks, experiment, and explore.

- TtvsFErFl09/26/2025

- riQAWzkXY08/29/2025

- CWQDNVdLH08/29/2025

- gTDPLXJgbYb08/29/2025

- tBBxONjyBElGZD08/29/2025