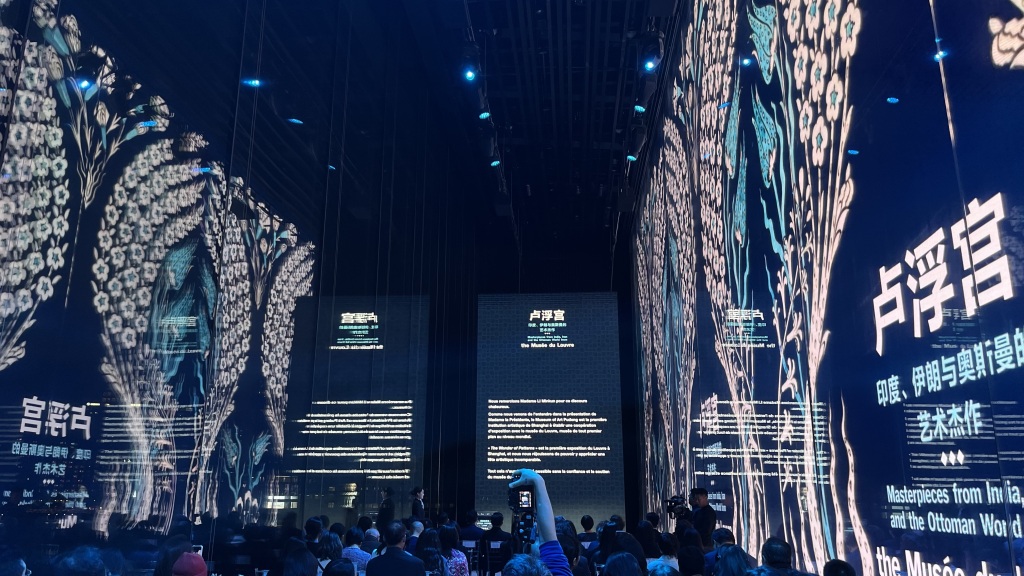

If you pause for half a minute in front of each exhibit, it will take nearly three hours to see all 300 works. Next to some of the works, you can also read beautiful verses. This is an exhibition that requires time to appreciate slowly. The exhibition "The Miracle of Patterns: Masterpieces of Indian, Iranian and Ottoman Art from the Louvre" from the Louvre Museum will be open to the public at the Shanghai Pudong Art Museum on December 13.

At the opening ceremony of ArtSurge, we saw that through these exhibits, we could not only see the amazing complexity of these empires in the field of art, but also feel the vivid and active cultural exchanges between these countries and civilizations. The influence of Chinese art on Islamic art is also clearly visible.

This exhibition features over 300 exquisite pieces from the museum's collection, showcasing the vibrant creativity of modern India, Iran, and Turkey. Focusing on the important regimes that ruled these three territories from the 16th to the 19th centuries—the Mughal Empire of India, the Safavid and Qajar dynasties of Iran, and the Ottoman Empire of Turkey—the exhibition emphasizes the impact of active trade between these empires on art.

This is the Ottoman exhibition hall, located on the fourth floor.

The opening ceremony was held in the Hall of Mirrors on the third floor.

Presenting the beauty of the pattern, a journey through time in an instant.

“This exhibition highlights the flow and dissemination of plant, geometric, and decorative patterns across time and space, and also presents the profound imagery and symbolic meanings contained within these patterns,” Aline François-Colin, Director of Exhibitions and Publications at the Louvre Museum, told ArtPulse. “The artists’ boundless creativity, poetic expression, and relentless pursuit of formal innovation are embodied in their original geometric patterns, the subtle interactions between color and light, and their exquisite craftsmanship. Through these exhibits, we not only see the astonishing complexity of these empires in the field of art, but also become aware of the vibrant and dynamic cultural exchanges between these countries.”

The Indian exhibition hall is based on ochre colors.

It is understood that the exhibition hall design was once again handled by Cécile Degos, the exhibition designer for the previous Orsay exhibition in France, "but the design style is completely different from that of the Orsay." Li Minkun, director of the Pudong Art Museum, said, "We conducted many studies when discussing the exhibition plan. These exhibits should be combined with the history, architecture, and living environment of that time. So we extracted some typical and very distinctive elements from these countries, and used some very exquisite architectural elements in the exhibition hall, and distinguished colors according to the different characteristics of the three countries. We used completely different but coherent designs to present the exhibits, so that everyone can have a very immersive experience, as if they have traveled to that era in an instant."

Iran Pavilion

“Art is interconnected, and we hope to present a dialogue between different art forms. In terms of spatial design, we also highlight the unique characteristics of these three regimes. The three halls are separated by three different colors to guide the audience's emotions and reinforce the intuitive distinction between the three major civilizations,” said Souraya Noujaim, Director of the Islamic Art Department. A large geographical map is placed in the corridor leading into the exhibition hall, marking not only the territories of India, Iran, and the Ottoman Empire, but also specifically marking the coordinates of Khotan (present-day Hotan) and Jingdezhen in China. Curator Judith Henon-Raynaud described the exhibition as “creating different jewelry boxes for different works.”

Reporters at the scene observed that many visitors had already found suitable angles for taking photos.

Three halls, each representing a different aspect of three civilizations.

The exhibition opens with a selection of artifacts from the collection of Louis XIV, the "Sun King" of France. Entering the ochre-themed Indian Hall, visitors are immediately drawn to exquisite jade daggers and intricately carved openwork window screens. The intricate and geometrically beautiful patterns on the screens become a popular spot for photos.

Dagger with horse-head handle, India, 17th century

Window screen, northern India, 17th century sandstone

From its founding in 1526, the Mughal Empire, at its peak, encompassed almost the entire Indian subcontinent. Historically, India, leveraging its geographical advantages, widely disseminated its indigenous culture and art to various regions. Architects, by integrating local styles with influences from Iranian and Central Asian art, developed a new architectural aesthetic. Mughal architecture often contains metaphors for sacred order, and its specific forms and meanings evolved with different regions and backgrounds. In its architecture, the filtering and diffusion of light served not only practical purposes but also aesthetic and symbolic significance. Whether it's the Jalli window, incorporating Iranian and Central Asian influences, precious jade and metal artifacts reflecting the fusion of local and Persian traditions, or various export items blending European and local styles, all demonstrate the Mughal Empire's artistic charm of inheriting its roots while innovating.

Iran Hall

Poetry Contest Panel, mid-17th century Iran, glazed pottery. This ceramic panel depicts a scene of two young men competing in poetry.

Book cover with a "rose and nightingale" motif, Iran, 1775-1825. Inscribed inside are lines from Saadi's poem "The Orchard".

Entering the Iranian Hall, the influence of blue and white porcelain is clearly visible. During the reign of Shah Abbas, domestic stability fostered trade prosperity, and the empire's exchanges with Europe grew increasingly close. He granted European merchants tariff exemptions, broke Portugal's maritime monopoly, and supported the development of the British and Dutch East India Companies. Goods from Europe and the Far East profoundly influenced Safavid production, especially in ceramics—local artisans strived to imitate and surpass imported blue and white porcelain and celadon. At the time, the Dutch, who controlled the spice trade, considered Chinese porcelain an important commodity, calling it "Kraak porcelain," a name likely derived from the Portuguese Krakshall ships that transported porcelain. In the mid-17th century, with the closure of Chinese ports, the Dutch turned to sources of blue and white porcelain from places like Kerman in Iran to fill the supply chain gap.

Ottoman Hall

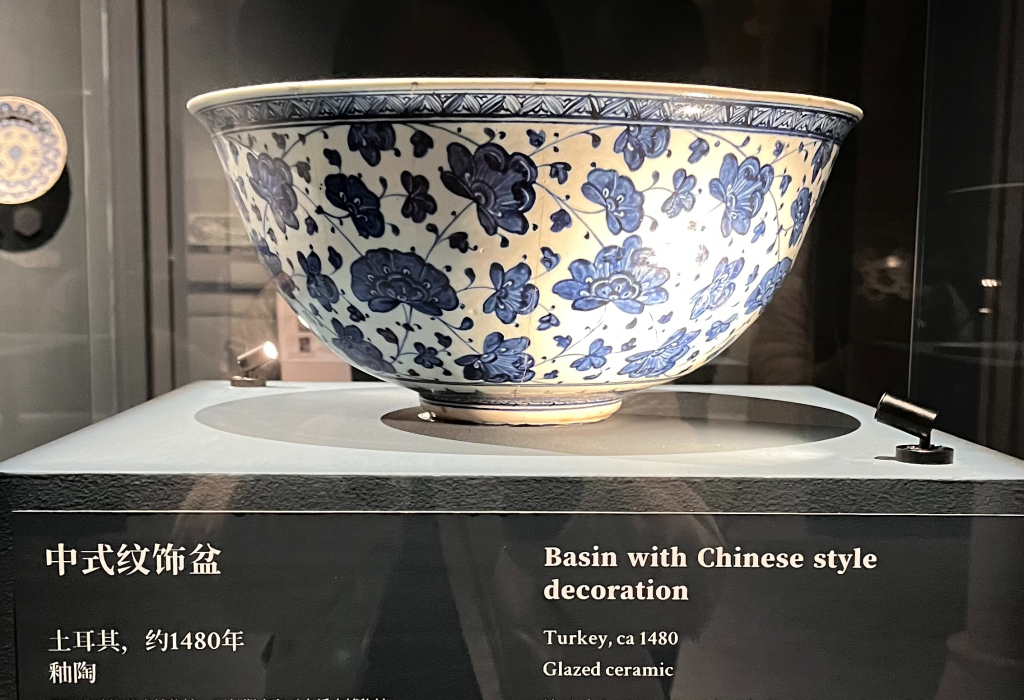

On the fourth floor, in the Ottoman Hall, visitors can see that the early ceramics of the empire continued the traditions of the previous dynasty. In terms of style, they were still mainly based on the blue and white colors of Chinese blue and white porcelain. The decorations were mostly composed of leaf patterns, geometric shapes, and floral patterns such as lotus and peony originating from Chinese ceramics—elements that were not uncommon in 15th-century Turkish and Iranian art.

Peacock-patterned plate, Iznik, Turkey, circa 1540–1555. Glazed earthenware, painted on a transparent underglaze slip.

The peacock-patterned plate is a key exhibit. While the plant motifs and color combinations on the plate are common in Ottoman ceramics of the 1540s and 1550s, bird motifs are extremely rare on surviving vessels. Therefore, the peacock pattern may have a deeper meaning. The Ottoman court was influenced by Persian culture, in which the peacock symbolized royal power and majesty.

From the 1530s onwards, ceramic colors gradually became richer, and compositions more dynamic. Slender, serrated leaf patterns became mainstream, and real flowers such as tulips, carnations, and roses began to be introduced. In the latter half of the 16th century, colors became even brighter, and new elements became more prominent. Ottoman potters often oscillated between realism and stylization. Based on an overall symmetrical layout or an underlying geometric grid (especially in glazed ceramic tiles), they artistically adjusted natural forms, making the patterns, while fulfilling decorative needs, sometimes approach abstract expression.

Curator's Interpretation: How Patterns Intertwine

Thanks to cultural exchange and mutual learning, foreign elements have been reinterpreted and transformed, influencing local creations and ultimately giving birth to artistic masterpieces with composite styles. "One is calligraphy, the second is plant patterns, such as naturalistic styles, and the third is geometric patterns," said Souraya Noujaim, Director of the Islamic Arts Department, mentioning peonies, lotuses, and animal patterns, such as dragons and birds. "These are all examples of Eastern vocabulary entering the Islamic world."

Chinese-style decorated basin, Turkey, circa 1480. The interior of this basin is decorated with a deep blue background with white space, and the decoration on the vessel wall imitates the blue and white porcelain of the Yuan Dynasty (1271-1368). Its stylized plant patterns are integrated with Chinese floral patterns.

Peony-patterned basin, Iran, 15th century

Furthermore, "trade, especially along the Silk Road and through maritime and land trade, had a profound impact on Islamic art." She encouraged visitors to carefully observe the cloud and wave patterns on the exhibits in the Ottoman section, noting that many originated in the East and appeared on precious materials such as jade, revealing the appropriation and borrowing of these patterns. In some Iranian pottery, the use of blue and white to depict patterns is also consistent with the style of Chinese porcelain.

Plate with dragon pattern

However, she also pointed out that there are differences in the fluidity of the depiction. These patterns became more rigid after they were transmitted to Islam, and this difference can be seen in the many dragon patterns on display.

The plate on the far left in the Ottoman Hall is a peacock-patterned plate.

Plates with plant motifs in the Ottoman Hall.

Plum blossoms, tulips, carnations, and cloud-patterned bricks, Iznik, Turkey, circa 1540–1545. Glazed pottery, painted on a transparent underglaze slip.

The exhibits, as described, mostly originated in the crossroads of imperial territories, regions deeply connected to both Eurasia and Asia. When presented side-by-side, viewers can almost hear the dialogue between these artifacts in terms of style, technique, and spirit, and appreciate how the influx of materials, texts, and patterns fostered aesthetic innovation within these interconnected empires. European botanical prints, introduced to the Mughal Empire, influenced local botanical designs; Chinese porcelain, transported from Europe and the Far East to the Safavid dynasty, provided inspiration for Safavid artisans. These transcontinental artistic connections will all be presented in the exhibition.

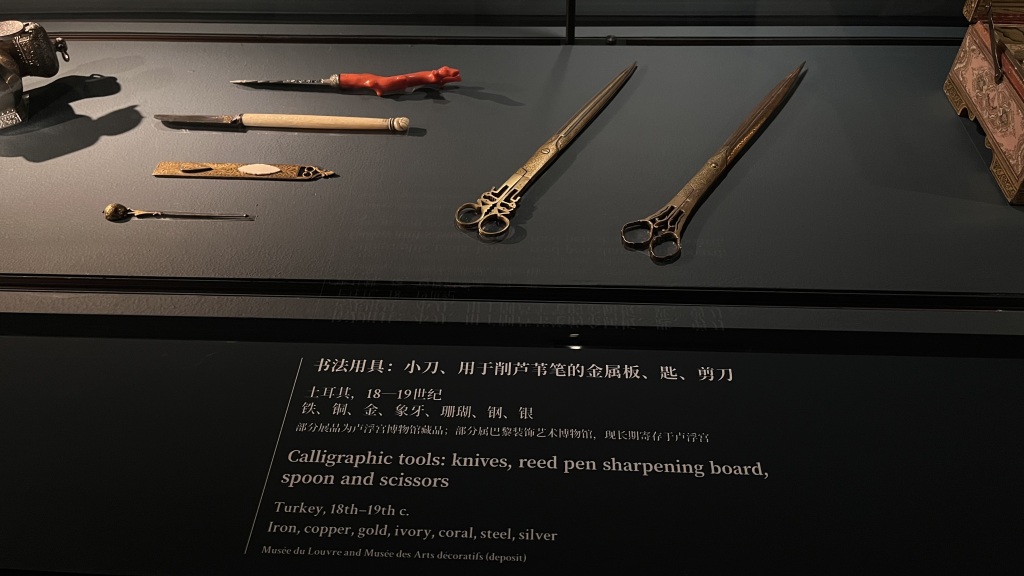

A quiet corner: calligraphy and a pencil case

A set of stationery was also placed in a quiet corner. “Calligraphy is a very important element in book design. You can see two styles: one similar to running script, and the other geometric. From a decorative and heritage perspective, it might be an ‘encounter’ with Chinese calligraphy, but their techniques are different. Chinese calligraphy uses a brush, while Islamic calligraphy uses a reed pen. It has now become a subject of much research. In 2020-2021, the Louvre held an exhibition in Abu Dhabi called ‘Dragon and Phoenix,’ which presented the connection between Asian and Islamic calligraphy,” said Suraya, Director of the Islamic Arts Department.

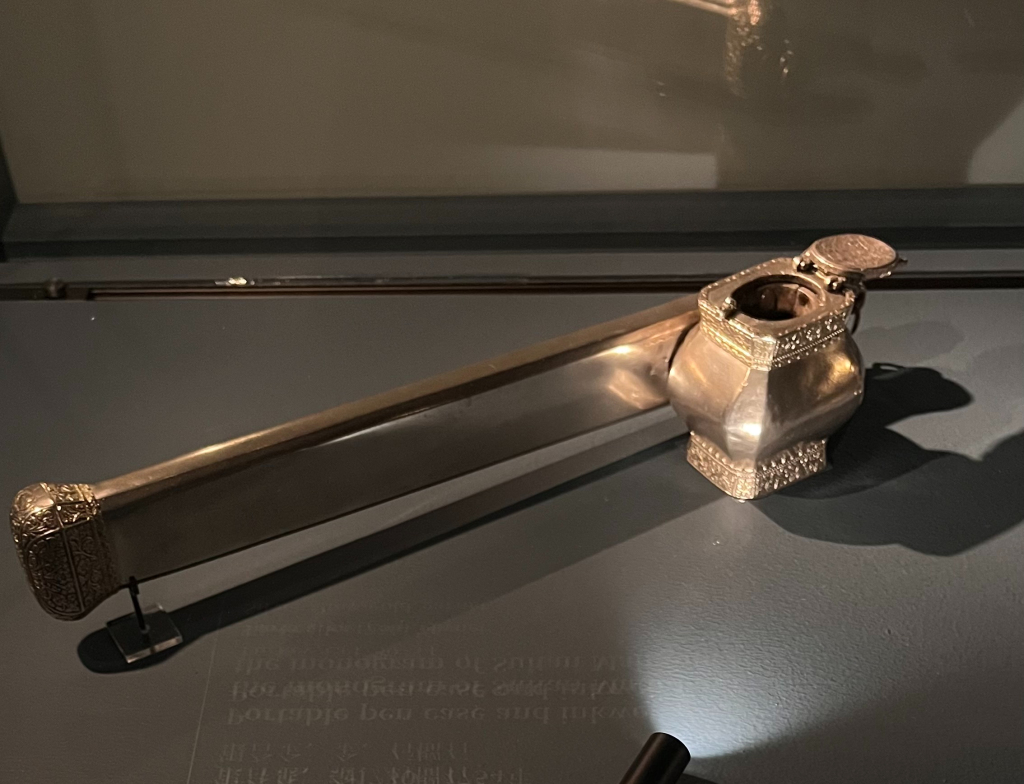

Portable pen case and inkwell bearing the monogram of Sultan Mahmud I, Türkiye, circa 1730–1754, made of silver alloy, gold, and garnet.

Calligraphy tools: knife, metal plate for sharpening reed brushes, spoon, scissors. Turkey, 18th-19th century. Iron, copper, gold, ivory, coral, steel, silver. Some exhibits are from the Louvre Museum collection, while others belong to the Musée des Arts Décoratifs in Paris and are currently on permanent storage at the Louvre.

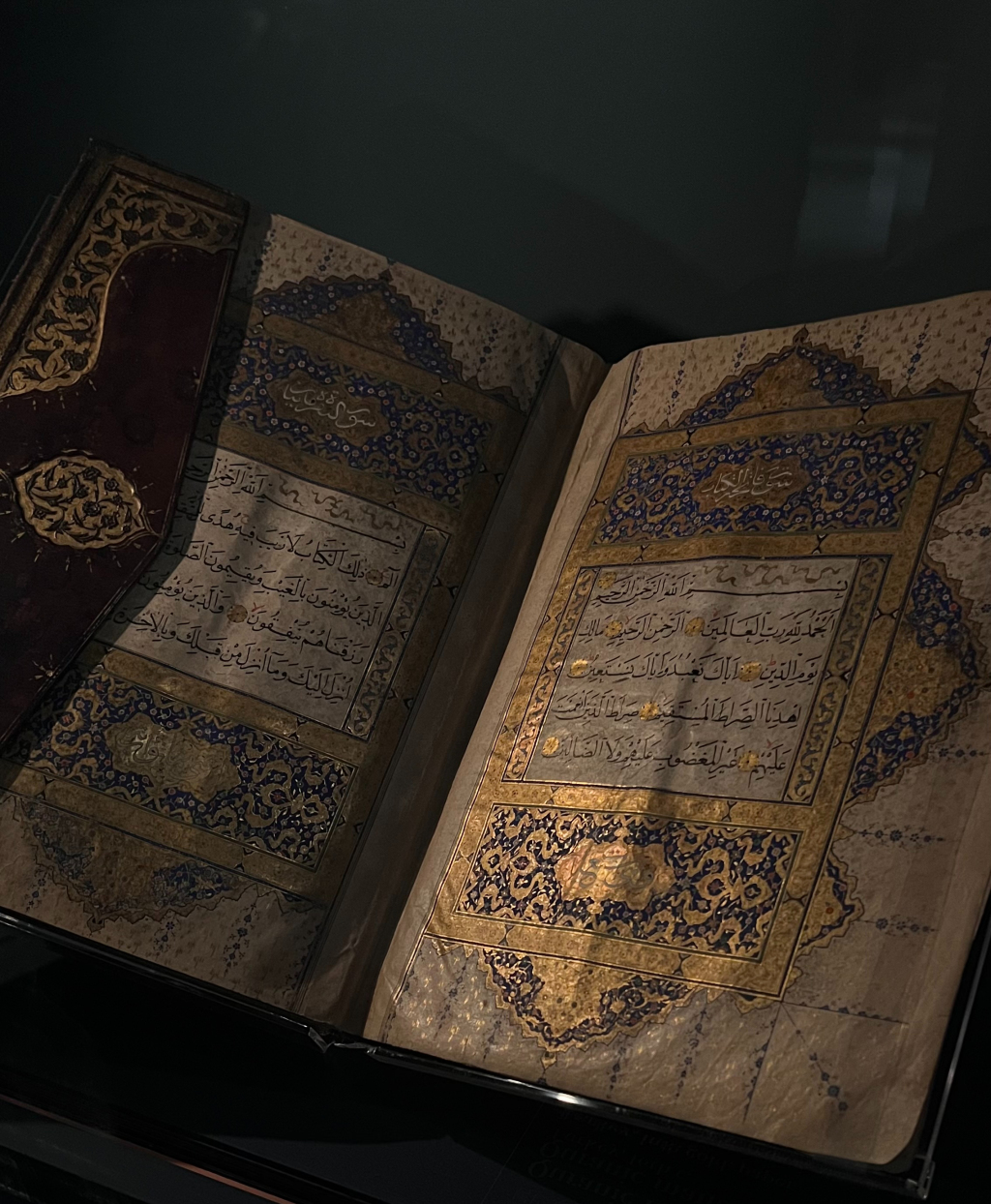

A Turkish manuscript of the Quran, 16th century, made of leather, ink, gold, and paper.

Writing is an important art form. Inscriptions were written in Ottoman Turkish, Arabic, or Persian. Ottoman Turkish, as the administrative language, was frequently used in official inscriptions, with poetic forms being more favored than prose. Among the various art forms, calligraphy occupies a pivotal position. Due to its unique rules and style, calligraphy emphasizes lineage and adheres to strict rules. Besides manuscripts, calligraphy often appears in the form of inscriptions, following specific combinations, in various creative works, especially in religious contexts. Inscriptions combined with geometric patterns or decorative motifs enhance architecture, ceramics, metalware, glassware, and textiles. In addition to its practical function, calligraphy also serves a decorative purpose, sometimes highlighting symbolic meaning.

The restored scene showcases life in the past.

Reconstruction of court life in Istanbul

A set of cups displayed on the right

On the fourth floor, the exhibition draws inspiration from decorative elements found in buildings such as Istanbul's Topkapi Palace, recreating a 17th-century court hall. The exhibits include original artifacts such as terracotta bricks, carpets, items in display cases, and stained-glass windows. A low table on the left is used for writing instruments, while a set of cups and pipes on the right evokes the consumption of coffee and tobacco at the time, accompanied by containers for various beverages. In the background, a jug and tray for handwashing are displayed.

The exhibition concludes with a restored room showcasing scenes of daily life in a wealthy family. It is explained that artworks like carpets, due to their fragility, require a six-year hiatus after the exhibition, and some may never have the opportunity to be exhibited again.

The exhibition will run until May 6, 2026.